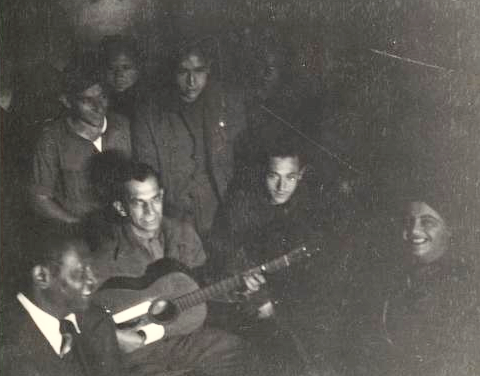

At a hospital base near Valencia, Spain, with an African American solider of the International Brigade. Sometimes under artillery and machine-gun fire, Robeson visited the shifting battlefronts to bolster the fighting spirit of the Republicans and their Communist allies with his songs. He befriended African American volunteers in the war against the fascist army of Generalissimo Francisco Franco.

Paul Robeson, Part II, focuses on the artist as a revolutionary. In the decade before World War II, he stood against racism, fascism, and colonialism, and campaigned relentlessly for social justice and human rights for all oppressed peoples. He paid particular attention to African independence movements, the struggle against U.S. Jim Crowism, and what Robeson perceived as a racially tolerant Soviet Union.

In the 1930s, Robeson would advocate throughout the world for working-class solidarity, which he believed would overcome divisive racism everywhere. His Depression-era campaigns for social justice would take him to the Soviet Union, which he admired for its racial tolerance, and to the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War in support of republican freedom fighters. He would be an unabashed advocate for the African independence movement and a student of African languages and culture. His theatrical and singing careers would thrive, and he would venture into films. At his side would be his wife, the indomitable Eslanda Goode Robeson.

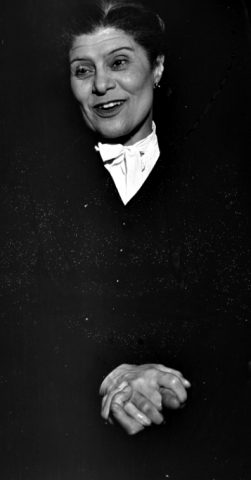

In 1930 Robeson performed as the eponymous lead in Shakespeare’s Othello—the first Black man in this role on the English stage since Ira Aldridge performed it in the mid-1800s. Robeson read all of Shakespeare’s plays, researched the historical contexts of the playwright’s works, and studied Shakespeare’s English language. He appeared opposite Peggy Ashcroft (later Dame Margaret Ashcroft) as Othello’s ill-fated wife Desdemona—an actress who soon became Robeson’s lover. As Robeson’s biographers document, his many affairs with prominent white women (including all his Desdemonas), a few of which endured for years, was a constant source of frustration for Essie, who was also Robeson’s business manager. Essie kept a diary of the many years of her troubled marriage. The London production at the Savoy Theatre played to glowing reviews in most of the major newspapers. In 1932, Robeson reprised Othello on the New York stage.

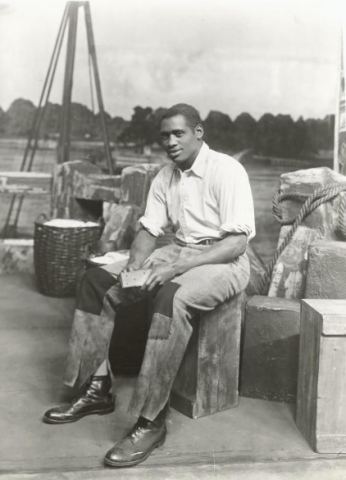

In 1930 Paul and Essie Robeson ventured into films, acting in the silent film Borderline, which was produced in Switzerland. Given the sensitivity of its subject matter it had only a limited art house distribution. For many years the film was believed to have been lost, but now Borderline is viewed as a classic example of avant-garde/experimental filmmaking. The film boldly depicts a depressed village and a married white man’s affair with Essie’s character, Adah, the sweetheart of Paul’s character, Pete.

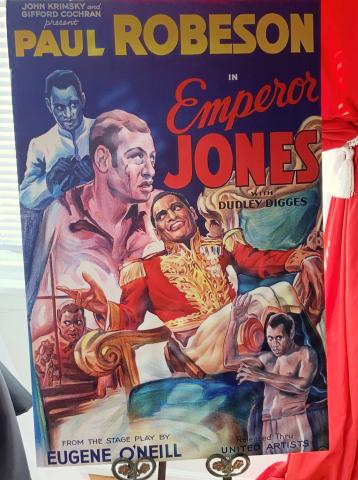

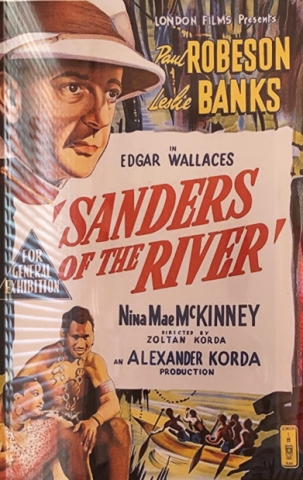

Robeson’s first film to target a wide audience was Emperor Jones in 1933. Filmed in New York, it was popular with Black audiences impressed with Robeson’s commanding performance, but was only a modest financial success. Back in London, Robeson, of immense linguistic ability, devoted himself to the formal study of African languages and Chinese; he would ultimately master thirteen languages fluently and sing in many more. Essie studied African anthropology. His studies prepared him for Alexander Korda’s production Sanders of the River, an African adventure story. Robeson thought the script offered the opportunity to portray Africans as real human beings, notwithstanding the film’s glorification of British colonialism and its attendant racial stereotypes; one of Robeson’s friends, the anti-colonialist activist Jomo Kenyatta, joined him on the set.

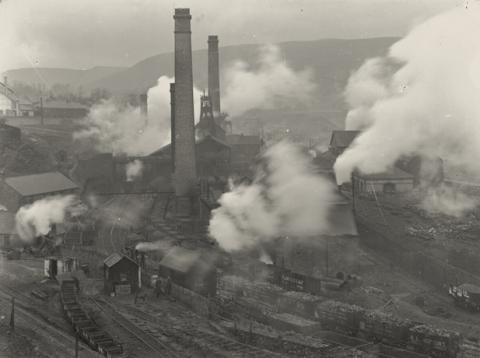

From 1929 to 1934, Paul, through his visits to the working-class communities of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, his association with British socialists, his African studies, and his association with anti-colonialist activists, saw how capitalist politics of hierarchy and privilege shaped racial and labor injustices. In the interwar years, his activities on behalf of low-income working people in the U.S. and Central America were far-reaching.

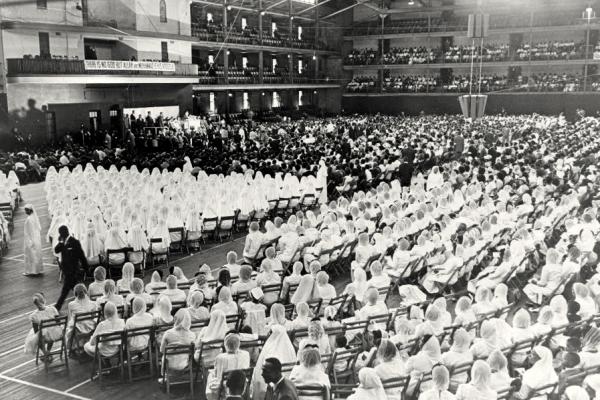

He sang to African-American tobacco workers in the Carolinas, in school yards and Baptist churches, around the campfires of Filipino and Japanese pineapple workers in Hawaii, to black and white stevedores and factory workers in union halls in Memphis, to Jewish-American garment workers in Catskill bungalow colonies and Bronx social halls, to Finnish miners in their social clubs in the Mesabi Range of Minnesota, to Mexican-American miners in Colorado and Arizona, to black Panamanian government workers assembled in a stadium in Panama City, to crowds of thousands of auto workers outside of factories in California and Michigan, to an audience of Canadian miners and metal workers on the border between Washington state and Vancouver, to congregations of his brother’s AME Zion church in Harlem.1

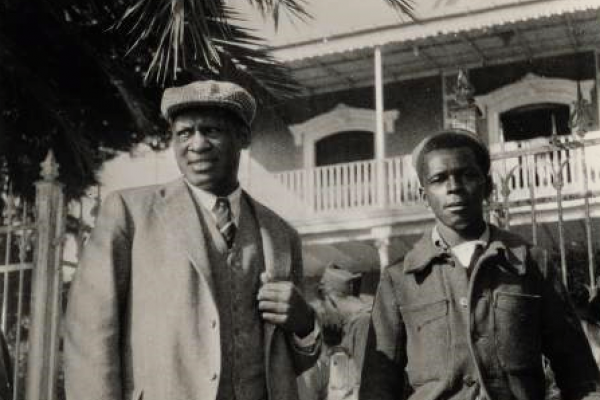

In 1933, Robeson enrolled in London University School of Oriental and African Studies, where he studied African languages, history, art, and folk music. He was involved politically as an honorary member of the West African Students Union. Through this organization, he began his lifelong friendship with Jomo Kenyatta, the future Kenyan revolutionary and the new nation’s first president after independence, and Nnambi Azikiwe, an independence leader in Nigeria. And during his extended time in London, he became friends with Kwame Nkrumah, leader of Ghana’s independence movement. Robeson asserted, “[I]n my music, my plays, my films I want to carry always this central idea: to be African. Multitudes of men have died for less worthy ideals; it is even more eminently worth living for.”2 He understood Africa as a continuing positive influence on Black Americans.

In 1934, he and Essie made their first visit to the Soviet Union via Berlin, where they were accosted by Nazi brownshirts and barely avoided a beating or worse; thus began Robeson’s commitment to anti-fascist resistance. The Soviet Union impressed the Robesons as a beacon of racial tolerance. Ever the autodidact and gifted linguist, Robeson would master the Russian language and classical Russian music, prose, and poetry.

In 1936, the movie Sanders of the River, its background scenes filmed in Africa, premiered in London, with Paul Robeson cast as the well-educated African chief Bosambo, who was allied with British colonialists. The film skewed heavily toward glorifying British imperialism following the director’s retakes, which would haunt Robeson. Yet the popularity of the film in England led Hollywood to cast him in the 1936 film version of Show Boat as Joe the Riverman, which this time allowed the power of his artistry to reach a national audience of Depression-era filmgoers.

A twelve-city concert tour took place in the Soviet Union in the fall of 1936. The Robesons enrolled their son, Paul Jr, in a Soviet school, where he would remain for two years and become a bilingual English-Russian speaker; his classmates included Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana, and foreign minister Molotov’s son.

Robeson was unaware of Stalin’s disastrous policy of agricultural collectivization from 1928 to 1933, which cost millions of lives and spawned labor camps (gulags). Stalin’s policy (dekulakization) primarily targeted the grain-rich (“black soil”) Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Here under dekulakization, the area’s wealthier peasant-farmers and known or suspected anti-Soviet resisters were killed or deported to gulags in Siberia and Kazakhstan. Stalin’s operatives forced the remaining peasantry onto collective farms. The Stalinists sold wheat and other grains produced in western Ukraine to Western Europe and the U.S. in exchange for hard currency. The Soviets could then purchase machinery for industrializing cities in eastern Ukraine and the Russian Soviet. The collectivized peasants who cultivated the grain were left to starve as the rest of the grain was dedicated to feeding urban industrial workers. This was a policy of “national terror”: Stalin intended to replace Ukrainian peasants with Russian farmers recruited from urban proletariats. In the end, the policy was a shambles: millions of peasants starved (a tragedy remembered as the Holodomor, the Great Starvation), and the collectives failed terribly.3

Benefiting from Western apathy and the Ukraine’s isolation, the Soviet state was able to keep the Great Starvation under international wraps and covered with elaborate lies told to its hungry Russian citizens. Paul Robeson would have had no reason to suspect that Stalinist Russia was not a haven of ethnic tolerance for Black Americans. The historian Timothy Snyder has written: “Moscow’s major claim to moral superiority, in a Europe where fascism and National Socialism were on the rise, and for American southerners journeying from a land of racial discrimination and lynchings of blacks [sic], was as a multicultural state with affirmative action. In the popular Soviet film Circus of 1936, for example, the heroine was an America performer who, having given birth to a black [sic] child, finds a refuge in the Soviet Union.”4

As for Stalin’s purges—the Great Terror of 1937 to 1938—Robeson publicly stated that they were justified in defense of the beleaguered Soviet state. The Soviet Union’s racial tolerance and opposition to colonialism and fascism, he would consistently argue, justified his sustained support, which made him an easy target of criticism for liberals and conservatives alike. Whatever doubts or criticisms he may have harbored about Stalin’s manic paranoia and horrific political cleansings, they were never publicly expressed.5

By the mid-1930s, Robeson was committed to fighting fascism and colonialism in a direct way as a “citizen of the world.” In 1936, when Paul’s filming schedule prevented him from accepting invitations to visit South and East Africa, Essie and Paul Jr. went instead and met with anti-imperialist leaders in those colonies. In 1945, Essie would publish African Journey, a well-received book of photographs that recorded her travels. From 1937, as co-founder and chairman of the Council on African Affairs, Paul would remain a strident critic of colonialism.

In 1938 Robeson sang to support the Spanish Republican resistance to Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s army revolt. With the aid of Nazi-German weaponry, Franco was fighting to overthrow the Republican government and establish a fascist dictatorship in Spain. Fifty years later, Robeson would write:

I went to Spain in 1938, and that was a major turning point in my life. There I saw that it was the working men and women of Spain who were heroically giving “their last full measure of devotion” to the cause of democracy in that bloody conflict, and that it was the upper class—the landed gentry, the bankers and industrialists who had unleashed the fascist beast among their own people.6

Sometimes under artillery and machine-gun fire, Robeson visited the shifting battlefronts to bolster the fighting spirit of the Republicans and their communist allies with his songs. He befriended African American volunteers in the International Brigade. As he put it, “I sang with my whole heart and soul for these gallant fighters.”9 Franco’s final victory with the fall of Madrid in March 1939, however, had always been a foregone conclusion as the U.S. and Britain refused to aid the Republican cause, and Hitler and Mussolini solidified and expanded their own dictatorships at the expense of Spain and other countries.

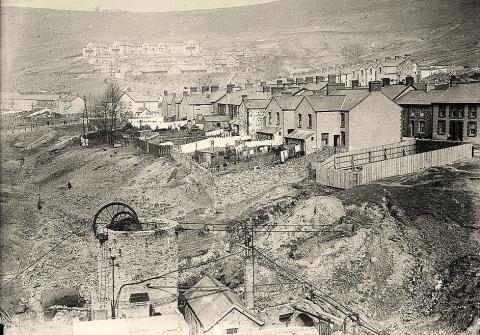

On September 30, 1939, with Britain and France now at war with Germany, Paul and Essie departed London on a dangerous voyage to the U.S. Robeson had just completed filming of The Proud Valley, a Welsh production that featured denizens of the Rhondda mining valley of South Wales as actors. In New York, Paul and Essie resided in Harlem, where Paul’s brother Ben Robeson was pastor of Mother A.M.E. Zion on 137th Street. Paul Robeson became close to Benjamin Davis of the Communist Party USA, which practiced interpersonal racial equality within its ranks and communicated with the Soviet Union through the Soviet ambassador to the U.S. He strengthened his popularity with American audiences through his radio broadcasts of “Ballad for America,” a paean song to democracy written for a Works Progress Administration (WPA) theater project. Notably, Paul chaired the Council on African Affairs, which promoted decolonization in Africa and the freedom of the world’s people of color.

In 1940, Robeson toured the U.S. as a concert singer, thrilling audiences with performances that included the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles and Chicago’s Grant Park, the latter attended by 165,000 Black and white Chicagoans, unusual for a city notorious for its anti-Black racism. Despite his popularity, in 1941 his friendship with the Soviet Union triggered what became a decades-long investigation of and attempt to discredit Robeson by the FBI, whose director, J. Edgar Hoover, was an obsessive anticommunist. Over the years thousands of documents would be compiled through surveillance activities and illegal wiretaps of Robeson, his family, friends, and associates—even in the war years, when the Roosevelt administration regarded Robeson as a political asset in the war against fascism. Hoover’s aim was to expose Robeson as a Soviet spy and a member of the U.S. Communist Party.

Robeson himself spoke of two wars—one against worldwide fascism, the other against racial segregation in the U.S. Accordingly, he scheduled part of his 1941 to 1942 concert tour for performances at two historically Black colleges in the Upper South. By assigning equal priority to both causes, Robeson drew the ire of administration officials, Black civil rights leaders, and the Communist Party USA, all of whom gave top priority to national unity in the war against fascism. Robeson, who counted Eleanor Roosevelt as a friend and ally, would never forgive her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933–1945), who for all his progressive New Deal social programs, refused to sponsor a federal antilynching law or to integrate the armed forces by executive order. Paul and Essie’s frequent lunches with the Indian anti-imperialist leader Jawaharlah Nehru was another source of government irritation. In the summer of 1942 Robeson appeared in Othello for a week in Cambridge, Massachusetts with Uta Hagen as Desdemona and José Ferrer as Iago. The following week he performed the play in Princeton, New Jersey—ironic given his father’s long-ago banishment by racist white Princetonians. The play with the same cast ran successfully on Broadway for a total of 296 performances, from October 1943 to the summer of 1944 and toured nationally from September 1944 to June 1945. On opening night Robeson received a twenty-minute standing ovation. Robeson’s Othello charted a path followed by the next generation of Black actors, including Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Cicely Tyson, James Earle Jones, and Sidney Poitier.

1. Mark Naison, “Americans Through Their Labor: Paul Robeson’s Vision of Cultural and Economic Democracy,” Ominira 1, no. 1 (1999), accessed from http://www.pipeline.com/~rgibson/paulrobeson.htm, 6 February 2022.

2. Paul Robeson, 1934, cited in Sterling Stuckey, “‘I Want to Be African’: Paul Robeson and the Ends of Nationalist Theory and Practice, 1914-1945,” Massachusetts Review 17, no. 1 (Spring 1976): 81.

3. Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010/2022), chaps. 2–3.

4. Ibid., 93. Orlando Figes, in Revolutionary Russia, 1891–1991 (New York: Pelican Books, 2014), notes that the rising threat of fascism worked to blind prominent Western intellectuals to the inherently violent nature of Stalin’s dictatorship. The mid-1930s, he writes, “was a time when Western intellectuals (the so-called ‘fellow travelers’) allowed their left-wing sympathies and fears of fascism to cloud their judgement of Soviet political realities. They saw progress in the Soviet Union but were blind to the famine and terror” (p. 295). Adam Hochschild, in The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin (Boston: Mariner Books, 1994/2003), ix-xx, lists Lincoln Steffens, Theodore Dreiser, George Bernard Shaw, Julian Huxley, and Beatrice and Sidney Webb as idealistic dupes of Soviet propaganda and chicanery.

5. For Stalin’s purges, see Hochschild, Unquiet Ghost, a compilation of survivors’ recollections of the Great Purge; Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (New York: Vintage, 1993), 456–510.

6. Paul Robeson, Here I Stand (New York: Beacon Press, 1988), 53.

A Note on Sources: Martin Duberman’s 800-page Paul Robeson: A Biography expertly charts the course of Robeson’s remarkable life and career and remains the single best and most cited Robeson biography. With Duberman’s careful attention to detail, his book is close to being a definitive biography, notwithstanding the 35-year time lag between its date of publication, 1988, and 21st-century medical advances and the contemporary Black Lives Movement. For my story collection, I have condensed and freely drawn from Duberman what I regard as the essentials of his narrative. Though limited as a historical study that adds to what Duberman describes as the turning points in Paul Sr.’s life, Paul Robeson Jr.’s two-volume biography, The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898–1939 and Quest for Freedom, 1939–1976, offers new, unvarnished details of Eslanda Goode Robeson’s tribulations as Paul’s lifelong business partner and financial manager, and her stressful marriage to Paul amidst his many extramarital affairs. Both Duberman and Paul Jr. are useful guides to Paul Robeson’s 1958 statement of beliefs, Here I Stand, from which I have quoted directly. A biography notable for its succinct identification of the dominant themes in Robeson’s melding of his artistry and radical political activity is Gerald Horne’s The Artist as Revolutionary. The most recent biography at this writing is 2020’s Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson, skillfully illustrated by Sharon Rudahl and edited by Paul Buhle & Lawrence Ware. This imaginative book interprets Robeson for 21st century audiences.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

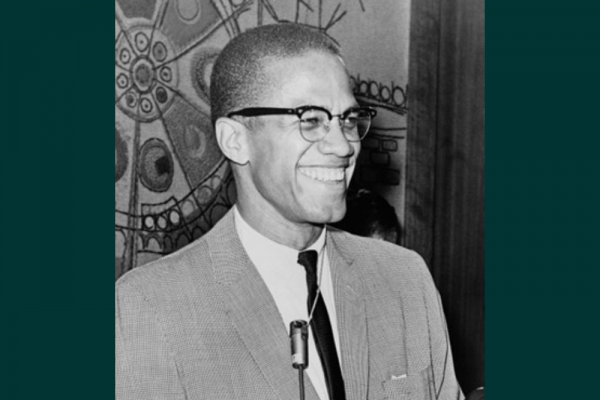

Stories in this Collection

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |