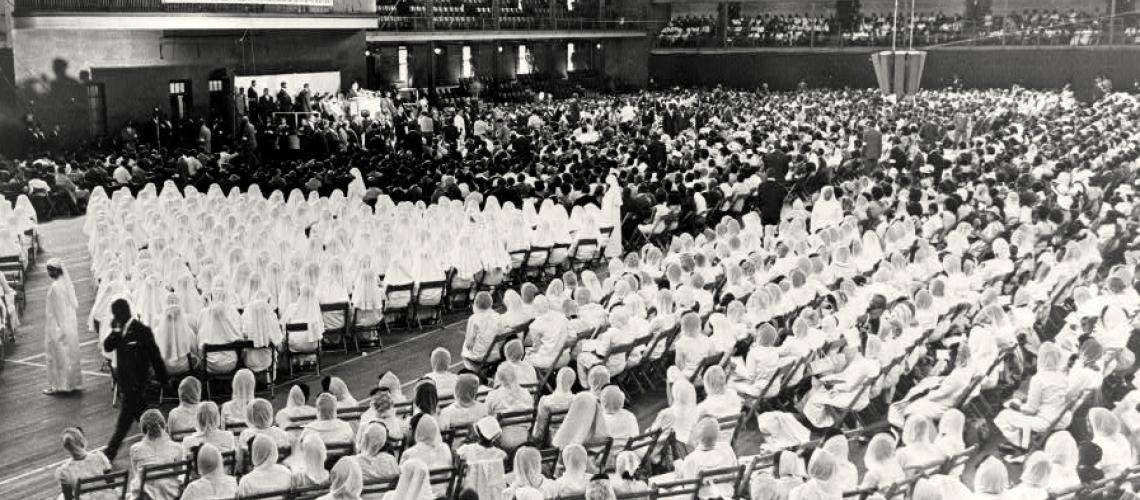

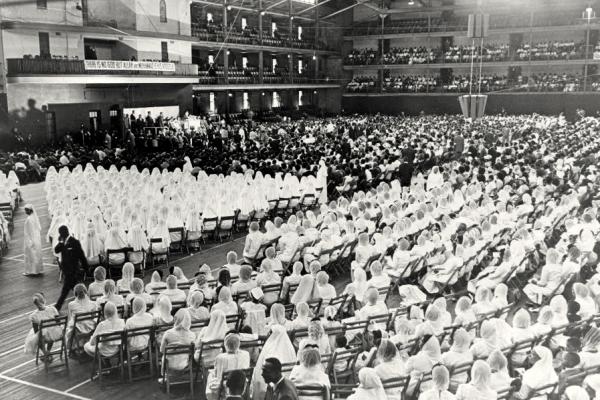

Elijah Muhammad addressing an assembly of his Nation of Islam followers.

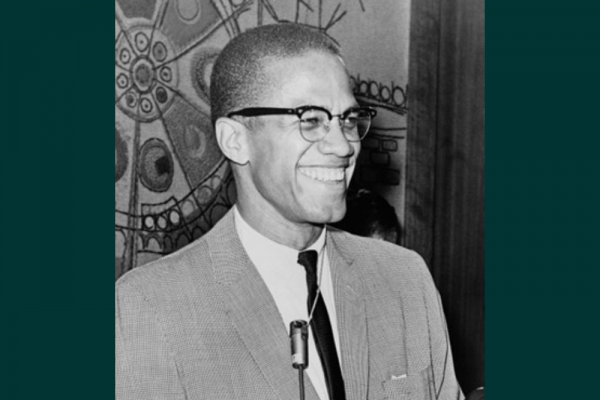

Malcolm X is the second iconic civil rights activist with an imprint on West Philadelphia. He belongs to a radical civil rights tradition that links him with Paul Robeson and Martin Luther King Jr. Part III looks at Malcolm’s meteoric rise in the Nation of Islam in the mid-1950s, his role for a time as Elijah Muhammad’s presumptive heir, and his 1960s drift to militant political activism in violation of Nation of Islam dogma.

By the mid-1950s, Malcolm X was the NOI’s leading national recruiter and organizer, and Elijah Muhammad’s likely heir. Malcolm founded or reorganized several East Coast temples, including Harlem (No. 7) and Philadelphia (No. 12). A strict adherent of NOI ideology, Malcolm imposed draconian rules of conduct on their memberships. Yet by 1960, Malcolm was undertaking political activity in violation of NOI ideology. He had also begun to doubt the validity of Elijah’s claim to be Allah’s Messenger and Elijah’s moral scruples. His doubts would set the stage for his public break with the NOI in 1964.

Malcolm X corresponded regularly during his prison years with the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad, known as The Messenger, was impressed by Malcolm’s devotion and dazzling intellectual and organizing skills; Malcolm put his skills to good use and recruited fellow inmates to the Nation of Islam (NOI). Malcolm would come to regard Elijah Muhammad as a surrogate father, a replacement for Earl Little, and over time Muhammad would regard Malcolm as a son, protégé, and heir apparent. While Malcolm’s self-reinvention meant divesting himself of his Detroit Red persona, he remained devoted to the radical uplift and self-determination of what sociologists of a later generation would call the Black urban underclass.

In 1952, at age 27, after six years of incarceration that included a return stint at Charlestown State Prison (1950–52), Malcolm X was paroled. While working in a retail store in Detroit, he proselytized for recruits to Temple No. 1. He was a harsh critic of old-guard members whom he believed were backsliding; their complaints about Malcolm’s strongarming asceticism reached Muhammad’s ears. Apparently worried that Malcolm wanted to control Temple No. 1, the Messenger of Allah, speaking from the NOI’s national headquarters in Chicago, forbade him to speak at any of the NOI’s six founding temples—Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., Cincinnati, and Baltimore. Instead, he gave him a different assignment.

Muhammad named Malcolm the Northeast regional NOI organizer over struggling, ill-disciplined new temples in Harlem, Boston, and Philadelphia. In short order, Malcolm reorganized the three temples, appointing himself principal minister of the Harlem (No. 7) and Philadelphia (No. 12) temples in 1954. He set Queens as his base and rapidly grew these regional temples. He was a stern taskmaster. For example, lecturing at the Philadelphia temple in 1955, Malcolm ordered local leaders to purchase scales and weigh members twice weekly; overweight members were given two weeks to lose ten pounds or be suspended until they met his draconian standard. Malcolm also announced that he would tolerate no criticism of his edict, on pain of expulsion from the temple. Eventually, Malcolm would control a dozen Northeast regional temples.

He also founded Temple No. 14 in Hartford, Connecticut. Malcolm’s expansion drew the ire of jealous ministers, Muhammad’s children, and the FBI, even as he poured money into the Chicago coffers. By 1955, Malcolm had FBI director J. Edgar Hoover on tenterhooks; Hoover deemed the wildly successful proselytizer a dire threat to urban stability and more broadly national security. Indeed, Malcolm adroitly marshalled statistics and historical data to document the validity of Muhammad’s attack on American racism—even as his astounding mastery of spoken polemics and zealous asceticism contrasted sharply with Elijah’s mysticism and frequent moral lapses.

In 1958 Malcolm married Betty Dean Sanders—thereafter known as Sister Betty X or Betty Shabazz. They had six daughters.

The NOI became national news in 1959, when Muhammad allowed the TV journalist Mike Wallace to produce a documentary titled The Hate That Hate Produced. On camera both Muhammad and Malcolm X proclaimed the divinity of all Blacks and labeled all American whites “devils,” “evil by nature,” or “blue-eyed devils.” The documentary also highlighted Muhammad’s karate-trained, muscular bodyguards, the Fruit of Islam (FOI). Yet bearing Malcolm’s stamp, the message to the NAACP and other nonviolent, pro-integration civil rights organizations was clear: Black resistance demanded a more aggressive form to unshackle the chains of white supremacy. Never mind Muhammad’s policy that the NOI forswore political activity. In the coming decade leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Black Panther Party would adopt Malcolm’s aggressive stance. It was Malcolm’s charisma, verbal adroitness, social analysis, and message of militant Black resistance—not the NOI’s religious dogma, Muhammad’s mystical beliefs, nor the Messenger’s rejection of politics— that attracted the 1960s generation of militant Black activists. Malcolm advocated eye-for-eye retaliation (retributive violence) if the FOI were attacked, although FOI violence was almost always directed against other Blacks. Increasingly synonymous in both the media and the public mind as the national face of the NOI, Malcom was a growing threat to Muhammad and his “Royal Family,” despite his continuing whirlwind fundraising for the NOI.

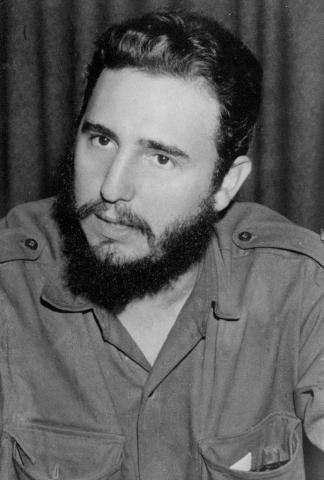

Malcolm’s status as the international face of the NOI was confirmed in September 1960 when he met with the new leader of revolutionary Cuba, Fidel Castro, in Harlem. That Malcolm did this without Muhammad’s authorization, infuriated the Messenger, as it signaled to the world that Malcolm had slipped his NOI leash to act independently of NOI leadership.

By the early 1960s Malcolm was actively transgressing Muhammad’s official policy of NOI nonengagement in political activism. To the Messenger’s chagrin, Malcolm emerged as a vigorous critic of the Kennedy administration’s waffling on civil rights. He would famously describe Kennedy’s assassination as “chickens coming home to roost.”

Malcolm’s zealous efforts to kick new life into the Chicago headquarters further undermined his relations with the NOI hierarchy, stoking fears that he was jockeying to be the next Messenger. Through informants and wiretaps, the FBI stirred this hornet’s nest, trying to undermine the NOI from within and to ensure that the NOI and the civil rights movement remained at loggerheads. Hoover’s strategy was to divide and conquer.

By the fall of 1960, Muhammad had ratcheted up his diatribes against “white devils” and the pro-integration stance of the civil rights movement. One of his media vehicles was the newsletter Muhammad Speaks, which Malcolm founded that year. Malcolm publicly supported Muhammad’s call for a separate Black state faithful to NOI doctrine, however quixotic that vision proved to be. For southern white supremacists, especially the Ku Klux Klan and White Citizens’ Councils, however, the more serious Black threat to their racist social order was the internationally celebrated Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose non-violent, integrationist stance was also anathema to Malcolm. By the spring of 1963, the national media was depicting the Black freedom struggle as an internecine war between Malcolm X and King—Malcolm as pariah, King as saint.

A Note on Sources for Malcolm X: Indispensable sources for the WPCH articles on Malcolm X are two Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies—Les Payne & Tamara Payne, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X (New York, 2020); Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York, 2011). These biographies provide additions and corrections to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as Told to Alex Haley (New York, multiple editions since 1966). The most recent authoritative source, also indispensable, is Peniel E. Joseph, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. (New York, 2021), a comparative biography.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |