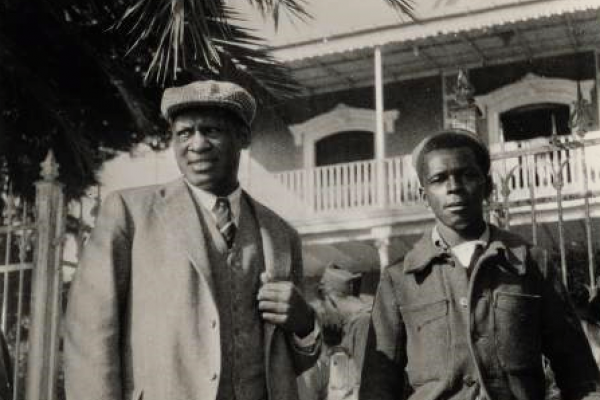

One of many images of Paul Robeson in the New York Public Library Digital Collections, a trove for researchers of the New York Theater.

Three heroic Civil Rights icons—Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. These biographies sketch out their lives and contributions, emphasizing their common ground as precursors to Black Lives Matter movement and the 1619 Project.

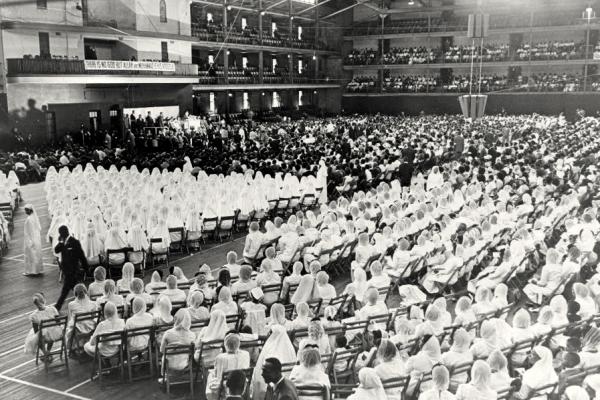

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project.

Continue reading Revolutionary Lives and a Shared Legacy

Continue reading Malcolm X, Part IV: Malcolm’s Rendezvous with Death and Beyond

Continue reading Malcolm X, Part III: Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam

Continue reading Malcolm X, Part II: Malcolm Little Becomes Malcolm X

Continue reading Malcolm X, Part I: Malcolm Little’s Coming of Age

Continue reading Paul Robeson, Part IV: Erasure from Historical Memory

Continue reading Paul Robeson, Part III: Freedom’s Price

Continue reading Paul Robeson, Part II: In the Arena for Human Rights and Dignity

Continue reading Paul Robeson, Part I: The Making of an International Icon

Stories in this Collection

Paul Robeson was born in 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, to a large family marked by tragedy and constrained by the racial mores of northern Jim Crow. Inspired by his indomitable father, a pastor of shifting religious allegiances, Paul surmounted these obstacles to graduate at the top of his class from Rutgers College, achieve All American status as a football player, and develop a remarkable talent as a bass-baritone singer. By the time he was thirty, he held a law degree from Columbia University and was a rising international star as a singer of Black spirituals and actor for stage and screen. |

In the 1930s, Robeson would advocate throughout the world for working-class solidarity, which he believed would overcome divisive racism everywhere. His Depression-era campaigns for social justice would take him to the Soviet Union, which he admired for its racial tolerance, and to the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War in support of republican freedom fighters. He would be an unabashed advocate for the African independence movement and a student of African languages and culture. His theatrical and singing careers would thrive, and he would venture into films. At his side would be his wife, the indomitable Eslanda Goode Robeson. |

Robeson’s life after the summer of 1945 was shaped by the ruthless politics of the nation’s Cold War with the Soviet Union. No individual in the twentieth century endured more sustained persecution and harassment from the federal government than Robeson in the 1950s. His true Achilles heel was his publicly expressed loyalty to the U.S. Communist Party (although he was never a member) and his oft-expressed sympathy with Stalinist Russia, whose murderous dictator Robeson refused to publicly disavow. His passport was suspended, and he was reviled by mainstream media. |

Robeson’s publicly avowed alliance with the U.S. Communist Party, his stalwart advocacy for socialism and labor justice, his relentless campaigns to end European colonialism, his continuing ties to the Soviet Union, and his refusal to defer to Jim Crow in any form resulted in a deliberate and largely successful campaign by federal agencies, mainstream media, and spiteful critics to efface the public’s memory of his exploits. Embittered and in declining health, he spent the last decade of his life (1966–1976) largely in the care of his sister Marian Robinson Forsythe at 4951 Walnut St. in West Philadelphia—an unjust ending to one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable lives. |

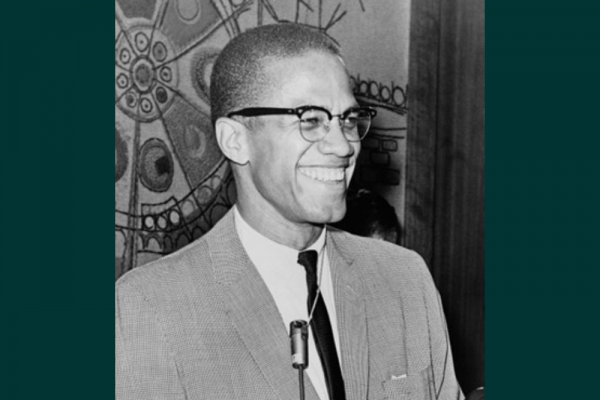

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little to Louise and Rev. Earl Little in Omaha, NE, in 1925. In 1928, the family settled in Lansing, MI. Malcolm’s parents were followers of Marcus Garvey, with Earl serving as an organizer for Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the Midwest. In Lansing, two tragedies befell the Little Family—Earl’s violent death and Louise’s mental collapse—with dire consequences for young Malcolm, who became a juvenile delinquent, using his natural good looks, rhetorical gifts, and acute intellect for petty criminal escapades. In the early 1940s, Malcolm shuttled from one menial job to another in Boston, where he lived with his half-sister Ella, and in Harlem, New York City. |

By the end of World War II, Malcolm Little had moved beyond petty crimes to heading a burglary team in Boston and its affluent suburbs. Adjudicated for these crimes, he would spend six years shuffling between different Massachusetts state prisons. Significantly, Malcolm used this time productively to educate himself in prison libraries, where he learned the fundamentals of effective rhetoric and oratory, as well history and philosophy. Malcolm also came under the influence of the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam (NOI). His conversion to the NOI was marked by his adoption of the name Malcolm X and his commitment to serve the NOI upon his return to society. |

By the mid-1950s, Malcolm X was the NOI’s leading national recruiter and organizer, and Elijah Muhammad’s likely heir. Malcolm founded or reorganized several East Coast temples, including Harlem (No. 7) and Philadelphia (No. 12). A strict adherent of NOI ideology, Malcolm imposed draconian rules of conduct on their memberships. Yet by 1960, Malcolm was undertaking political activity in violation of NOI ideology. He had also begun to doubt the validity of Elijah’s claim to be Allah’s Messenger and Elijah’s moral scruples. His doubts would set the stage for his public break with the NOI in 1964. |

In March 1964, Malcolm X publicly broke with the NOI to form the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) and his religious branch, Muslim Mosques, Inc. (MMI). This eventful year included Malcolm’s pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca, his conversion experience, and several months spent in Africa and the Middle East studying orthodox (Sunni) Islam and conferring with leaders of post-colonial nations. His public repudiation of Elijah Muhammad and rejection of NOI “truths” formed the backdrop of his assassination by NOI operatives in Harlem on 21 February 1964. |

While Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. started from vastly different places in society, by the time of their untimely deaths their profound understandings of historically entrenched structural inequities—tracible to 300 years of Black enslavement and more than a century of white supremacy and stark discrimination in the distribution of social and economic goods—were in close alignment, as were their goals for social justice and beneficial goods in all matters of race. The historian Peniel Joseph offers a robust analysis of this alignment in his 2021 book The Sword and the Shield, arguing that Malcolm and King were at heart radical militants. Joseph’s analysis, however, overlooks the pathbreaking civil rights militancy of their older contemporary, Paul Robeson. This story offers a corrective. |