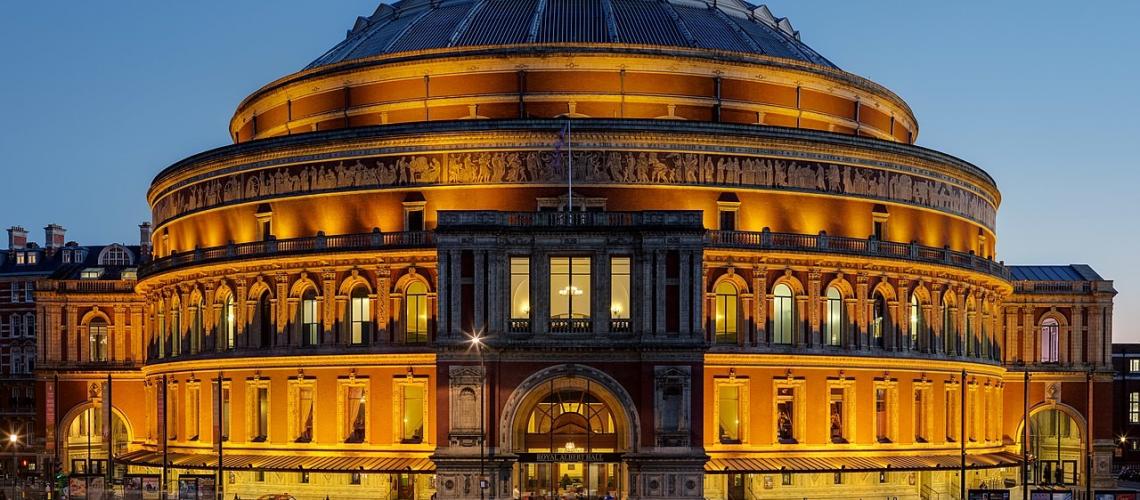

The restoration of Paul Robeson’s passport enabled him to travel to Europe and the Asian outposts of the Soviet Union. In summer 1958, he gave a sold-out concert at Royal Albert Hall—shown here in its contemporary version as viewed from Kensington Gardens, London—accompanied by Larry Brown at the piano. (The concert hall’s exterior has been fundamentally unchanged since its opening by Queen Victoria in 1871.) Robeson had first performed here to critical acclaim in 1929. Royal Albert Hall, Carnegie Hall, and the Hollywood Bowl were among the prestigious venues graced by Robeson during his illustrious singing career—and there were the countless halls and parks where he sang to working class audiences following his turn to social activism in the 1930s.

Part IV focuses on the final chapter of Paul Robeson’s eventful life when his myriad leftist political activities and stated views resulted in a deliberate and largely successful campaign by federal agencies, mainstream media, and other hostile critics to erase him from historical memory. Robeson was compelled to live out his remaining days in relative obscurity and declining health.

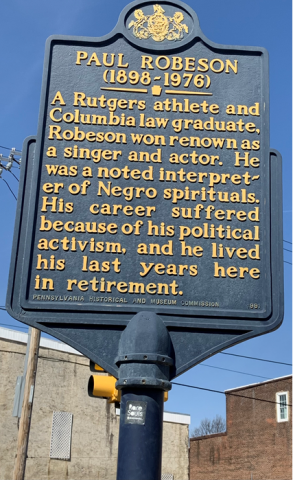

Robeson’s publicly avowed alliance with the U.S. Communist Party, his stalwart advocacy for socialism and labor justice, his relentless campaigns to end European colonialism, his continuing ties to the Soviet Union, and his refusal to defer to Jim Crow in any form resulted in a deliberate and largely successful campaign by federal agencies, mainstream media, and spiteful critics to efface the public’s memory of his exploits. Embittered and in declining health, he spent the last decade of his life (1966–1976) largely in the care of his sister Marian Robinson Forsythe at 4951 Walnut St. in West Philadelphia—an unjust ending to one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable lives.

Condemned by the media and the federal government, Paul Robeson was banned during the 1950s from the venues essential to his career and income: concert halls, stages, movie screens, radio, and television. Only union halls and Black churches remained open to him. Dire poverty, however, was not Essie and Paul Robeson’s fate; their previous investments and Paul’s royalties kept them afloat, even as his films and recordings were withdrawn from circulation in the U.S.

The loss of his passport made it impossible for Robeson to continue his career abroad. The nation’s leading newspapers and periodicals refused to review his memoir, Here I Stand, a brief account of his youth and beliefs. It was published in 1958 by Othello Associates, which was run by his son Paul Jr. The book was little noted and was soon out of print until thirty years later, when Beacon Press released a new edition during a revival of interest in Robeson. In a speech to a Harlem audience, W.E.B. Du Bois, himself no stranger to anticommunist witch hunts (he was stripped of his passport in 1956), underscored the irony of Robeson’s ostracism in the U.S. “He is without doubt today, as a person, the best known American on earth, to the largest number of human beings. Only in his native land is he without honor and rights.”1

The labor historian Mark Naison remarked on Robeson’s “virtual erasure from historical memory”:

What does it say about America that the most talented African-American of the century, a scholar, athlete, artist and human rights activist, a man whose singing voice sent chills through those who heard it and who mastered thirteen languages could be turned into a non-person by the hysterical manipulation of public opinion? Paul Robeson broke no laws. His crime, to those who attacked him, was that he refused to denounce the Soviet Union as the major source of evil in the world and to sever ties to American communists he worked with in civil rights organizations, labor organizations, and campaigns to end European colonialism. The political and cultural leaders of the United States were so threatened by Robeson’s political outlook and his utter lack of deference to the leaders of white America, that they decided to make an example of him that would redound through the ages.2

As the legal historian and Robeson biographer Paul Von Blum puts it:

The timidity (and sometimes the complicity) of thousands of intellectuals, including academics, in the face of anti-leftist hysteria, Congressional investigations, blacklisting, and FBI surveillance of tens of thousands of law-abiding citizens remains an egregious blight on American intellectual and political history. Paul Robeson, in contrast, remained courageous and outspoken, at enormous personal cost. History’s judgment on which stance is superior should be unambiguous: it is better to be active and occasionally mistaken than to acquiesce in evil.3

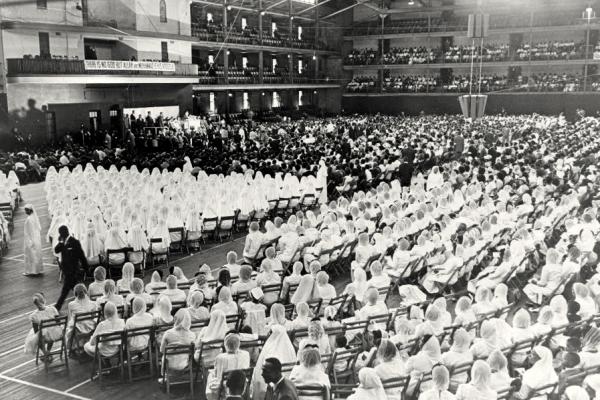

The late spring of 1958 marked the end of Paul’s harrowing eight-year passport ordeal. In a 5-4 ruling in a case that did not involve him directly, the Supreme Court declared as unconstitutional the State Department’s denial of a passport because of a citizen’s political beliefs. The Court also negated the Passport Division’s policy of requiring a signed affidavit regarding Communist Party membership. Nonetheless, the FBI continued its wiretaps. At last Paul Robeson could travel to Britain, where he and Essie hoped to reboot his career. Though there were grumblings in the British press and Parliament, Robeson was allowed to return to London that summer, where he sang at London’s Royal Albert Hall. In August he traveled to Moscow, where he gave a concert in the Lenin Sports Stadium prior to traveling by train to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where he collapsed from heat exhaustion and needed a month to recuperate. The Robesons returned to London in the fall, where Paul gave a historic recital at St. Paul’s Cathedral during Evensong, the storied church’s first such break with a centuries-old tradition. Back in Moscow on New Year’s Eve, he joined W.E.B. Du Bois at a formal New Year’s Eve celebration in the Kremlin hosted by the Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev led the applause for the two great civil rights activists. But suffering from exhaustion, Paul Robeson spent the next two months, first at a Moscow hospital, then at the Barvikha Sanitorium for government officials and notable foreign diplomats.

Robeson reappeared in England in the spring of 1959 as the lead in a new production of Othello at Stratford-on-Avon, which included, among other rising stars, Albert Finney, and in crowd-scene roles Diana Rigg and Vanessa Redgrave; the production would run periodically through the fall. Robeson was hardly his robust self of earlier decades, and director Tony Richardson cut his weekly schedule from four performances to two.

1959 was the year of South Africa’s Sharpsville Massacre, and Robeson, despite some bad days, continued to advocate for social justice for that apartheid country’s oppressed Black population; he traveled on the Continent to attend socialist and peace conferences; and he undertook a 32-city concert tour across Britain.

A dozen African nations declared their independence in 1960. There was a growing militancy in the Black struggle for social justice in the U.S., with the spread of student sit-ins, the formation of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and growing support from Northern white liberals. Robeson was skeptical that the newly elected Kennedy-Johnson administration would improve conditions for southern Blacks. Preparatory to what Essie called Paul’s “rat race” of commitments, he shed 40 pounds in 40 days after his weight had ballooned to 285 pounds. Then he embarked on a grueling schedule of concerts starting in East Germany.

Paul arrived in East Berlin on October 4, 1960, together with his pianist Bruno Raikin. German authorities had organized a tightly packed itinerary of meetings, concerts, and official ceremonies for the first nationally celebrated Black activist to visit their country. Robeson received an honorary doctorate from the Humboldt University and a prize from the East German Peace Council, performed for the members of the Free German Youth (FDJ), attended a reception with high-ranking politicians, visited a state-owned enterprise, and held a press conference. Judging by Robeson’s public statements, the trip exceeded his expectations. For instance, at the concert for the Free German Youth, Robeson said: “This has been without question [. . .] one of the most moving days of a long 62 year old life. And I want to thank you here in the German Democratic Republic for your warm welcome to me, not only to me, but to the people from whom I spring, from the Negro people of America.”4

Australia and New Zealand were next on his itinerary. Provoked by unfriendly Australian reporters, Robeson furiously vented his pent-up rage over his decades-long harassment by the U.S. government, vowing that in a war with Russia, he would support the Russians. This was an early harbinger of his mental unraveling.

While in Moscow, on March 27, 1961, a week before his 63rd birthday, Robeson slashed his wrists, although not with deep cuts. He was hospitalized and diagnosed as suffering from paranoia and extreme anxiety. Robeson’s son Paul Jr. speculated, though without hard evidence, that his father was drugged by the CIA, which he alleged conspired to prevent his father from making a planned trip to Cuba. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion by Cuban exiles to topple Castro’s communist regime, which was backed by the Kennedy administration, took place on April 17. After a three-month convalescence at the Barvikha Sanitorium, he returned to London, where he underwent a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); the treatment offered some relief. But in the spring of 1963, Essie, dissatisfied with the progress of Paul’s recovery, had him flown to a clinic in East Berlin where the preferred mode of treatment was psychotherapy. Paul remained there through the late fall before returning with Essie to the U.S.

Robeson’s health was now irreparably broken. He and Essie returned to a house they had purchased years before at Jumel Terrace in Harlem, and Paul spent the early months of 1964 there and at his sister Marian Robeson Forsythe’s house at 4951 Walnut Street, in West Philadelphia. In his first public statement to the press, he applauded the militant Black activists of the civil rights movement and their white allies, hailing the integrative quality of the turn toward militancy.

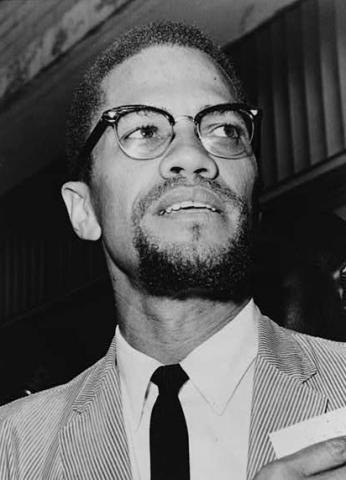

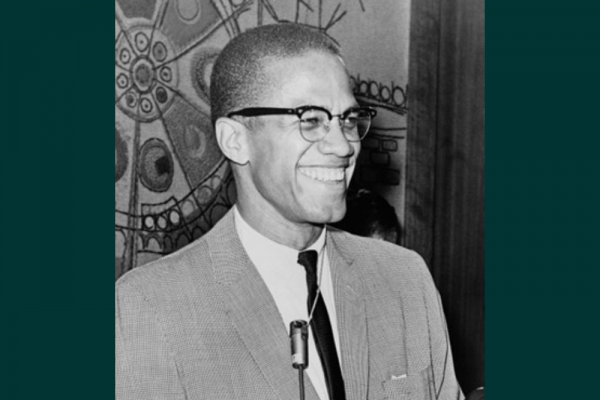

For the first time, in January 1965, his path almost crossed with Malcolm X, whom Paul admired for the internationalist stance that Malcom adopted after his visit to Mecca. Malcolm in turn admired Robeson for his 1949 stand against Blacks rallying to the defense of a country that “treated them with such open contempt and bestial brutality.”5 The occasion was the Harlem funeral of the Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Paul Jr. arranged for the two men to delay their first meeting until after tensions eased between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad and the separatist Nation of Islam (NOI). The meeting never happened. A month after Hansberry’s funeral, Malcolm was assassinated by NOI operatives.

Suffering a severe psychiatric relapse, Robeson made a second unsuccessful attempt at suicide. On June 11, 1965, he was admitted to Gracie Square psychiatric hospital. He was deeply angered at being ignored by the current generation of civil rights activists and the lack of recognition accorded his role as a pioneer of the civil rights movement from the 1920s–1940s. Perhaps compounding his depression was the loss of his audience and the human contact and adulation he had enjoyed with so-called ordinary people through his singing, stage performances, and political speeches.

By now Essie Robeson, Paul’s beleaguered mainstay support for 43 years, was hospitalized. She died of metastatic breast cancer on December 12, 1965 at Beth Israel Hospital on the eve of her 70th birthday.6 Paul was too distraught to attend her funeral.

Paul Robeson’s final decade (1966–1976) was spent in the care of his older sister, Marian Forsythe, at her home at 4951 Walnut Street in West Philadelphia. Marian had been educated at the Scotia Seminary for young Black women, founded in 1867 in Concord, North Carolina (now Barbara Scotia College). Widowed since 1959, she was a retired Philadelphia school teacher who lived with her daughter Paulina. Marian was overly optimistic that she could nurse Paul to recovery. Paul Jr. would later write that the drugs Paul Sr. received at Gracie Square had a toxic effect that contributed to his decline.

As for the underlying cause of Paul’s mental disorders—one that may have underlain other bouts of depression and anxiety—"insecurity in early childhood, [the] burden of representing an entire race, more than a decade of government persecution, heartbreak at the failures of communism”:

In Robeson’s time people were secretive about mental disorders. Only his close friends knew how impaired he became. But early in the twenty-first century retired athletes came out about memory loss, depression, anxiety. Too many took their own lives. Dozens donated their brains for study after death. A 2017 study of the brains of 111 National Football League players had the damage now diagnosed as CTE—chronic traumatic encephalopathy [as reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association.]

Paul Robeson played fierce tackle football from boyhood. Maybe there is no mystery. Maybe like many a Black man before him and since, he simply took too many blows to this head.7

In 1967, Who’s Who in American History included his biography. Rutgers University founded the Paul Robeson Cultural Center, the first Black cultural center on a U.S. campus. Paul’s 70th birthday was celebrated in New York and Moscow via a radio hookup. As part of its elaborate celebration, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) established a Paul Robeson Archive.7 Distinguished British artists, including Peter O’Toole, Michael Redgrave, and Peggy Ashcroft, paid tribute to Paul in an evening of music, poetry, and drama at an annex of London’s Royal Festival Hall; artists who could not attend, such as John Gielgud and Yehudi Menuhin, sent glowing messages.

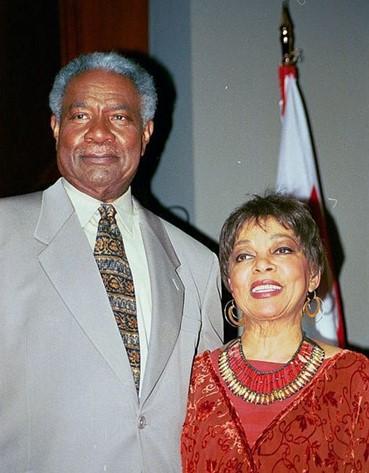

Though Robeson was no longer a household name, he was honored in select circles and, in the 1970s, presented with some major awards. Although his weak health precluded his father’s attendance, Paul Jr. and Harry Belafonte organized a gala celebration for Robeson’s 75th birthday at Carnegie Hall; the multi-media program was attended by luminaries such as Odetta, Leon Bibb, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte (the program’s producer), James Earle Jones, Roscoe Lee Brown, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee; Pete Seeger sang honoring Paul’s courageous performances for Republican soldiers during the Spanish Civil War; Delores Huerta of the Farm Workers Union gave a rousing speech honoring Paul’s legacy for migrant farm workers; Coretta Scott King spoke of the common ground Paul shared with her husband as warriors of the civil rights movement.

Paul Robeson died at West Philadelphia’s Presbyterian Hospital (today’s Penn–Presbyterian Medical Center), from complications of a stroke, on January 23, 1976. His funeral service at Mother A.M.E. Zion Church in Harlem, where Paul’s brother Ben had pastored for 27 years, drew thousands to the rain-drenched streets outside the historic church. Inside the church, writes Martin Duberman, were:

Old Left and New, theater people and trade-unionists, white and black, Communists and conservatives, dear friends, old adversaries, complete strangers. A Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin showed up; so did Harry Belafonte; Uta Hagen; Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz; and Paul’s Rutgers sweetheart, Maimie Neale Bledsoe; do did Steve Nelson of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and Harry Winston, national chairman of the CPUSA . . . and hundreds of Harlem’s so-called ordinary people.8

1. Quoted in Gerald Horne, Paul Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary (London, UK: Pluto Press, 2016), 3–4.

2. Mark Naison, “Americans Through Their Labor: Paul Robeson’s Vision of Cultural and Economic Democracy,” Ominira 1, no. 1 (1999), accessed from http://www.pipeline.com/~rgibson/paulrobeson.htm, 6 February 2022.

3. Paul Von Blum, “Paul Robeson: The Quintessential Public Intellectual,” lecture at the Lafayette College (Easton, PA), Paul Robeson Conference, 7 April 2005, as a part of the three-day Paul Robeson Conference on the history and culture of civil rights and civil liberties.

4. Maria Schubert, “Allies Across Cold War Boundaries?” Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte 33, no. 1 (2020): 61.

5. Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography (New York: New Press, 1989), 527–28.

6. In Eslanda: The Large and Remarkable Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2013), Essie’s biographer, Barbara Ransby, summarizes this remarkable woman’s achievements outside of her marriage to Paul:

College educated when most Black women were working as domestics, Essie in the 1920s became the first Black women [sic] chemist to work in a pathology laboratory at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City and the first Black woman to head such a unit. In the 1930s, she studied with renowned anthropologist Branislaw Malinowski at the London School of Economics and later pursued a Ph.D. in anthropology. She published three books, one of which was co-authored with the Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl Buck. For nearly twenty years, she worked as a freelance journalist, a U.N. correspondent, and a writer, analyzing international affairs and domestic politics. She wrote hundreds of essays and articles and delivered hundreds of lectures throughout the United States and around the world in which she spoke out against racism and injustice. By the 1940s, she had become an uncompromising voice for a range of progressive and left-wing causes, most notably independence for African nations still suffering under colonial rule. She publicly allied herself with militant anti-colonial campaigns, and with the world communist movement, at a time when such stances were both controversial and dangerous. (p. 2)

7. Sharon Rudahl, illustrator; Paul Buhle & Lawrence Ware, eds., Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020), 117.

A Note on Sources: Martin Duberman’s 800-page Paul Robeson: A Biography expertly charts the course of Robeson’s remarkable life and career and remains the single best and most cited Robeson biography. With Duberman’s careful attention to detail, his book is close to being a definitive biography, notwithstanding the 35-year time lag between its date of publication, 1988, and 21st-century medical advances and the contemporary Black Lives Movement. For my story collection, I have condensed and freely drawn from Duberman what I regard as the essentials of his narrative. Though limited as a historical study that adds to what Duberman describes as the turning points in Paul Sr.’s life, Paul Robeson Jr.’s two-volume biography, The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898–1939 and Quest for Freedom, 1939–1976, provides new, unvarnished details of Eslanda Goode Robeson’s tribulations as Paul’s lifelong business partner and financial manager, and her stressful marriage to Paul amidst his many extramarital affairs. Both Duberman and Paul Jr. are useful guides to Paul Robeson’s 1958 statement of beliefs, Here I Stand, from which I have quoted directly. A biography notable for its succinct identification of the dominant themes in Robeson’s melding of his artistry and radical political activity is Gerald Horne’s The Artist as Revolutionary. The most recent biography, at this writing (fall 2022) is 2020’s Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson, skillfully illustrated by Sharon Rudahl and edited by Paul Buhle & Lawrence Ware. This imaginative book interprets Robeson for 21st century audiences.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |