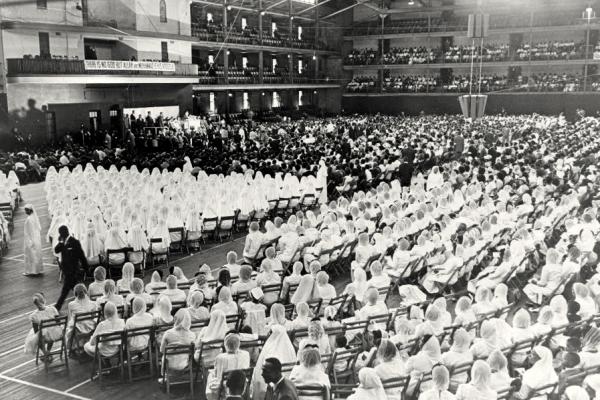

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addresses over 10,000 attendees at the “Freedom Now Rally” at 40th St. and Lancaster Ave., West Philadelphia. King also held “Freedom Now” rallies in Chicago, Cleveland, and Boston.

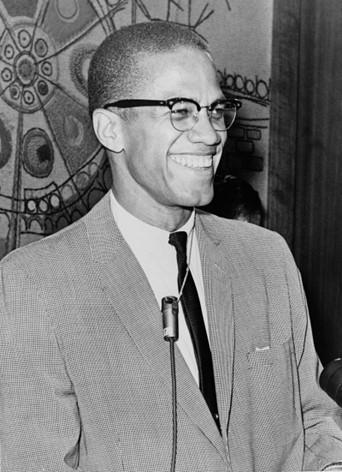

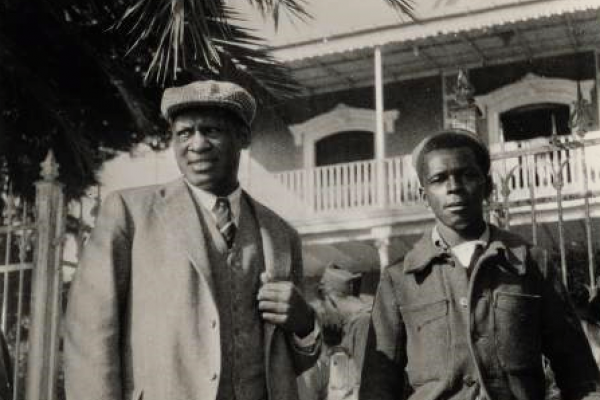

Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. were militant activists who shared common ground as heroic civil rights icons and left their marks on West Philadelphia.

While Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. started from vastly different places in society, by the time of their untimely deaths their profound understandings of historically entrenched structural inequities—tracible to 300 years of Black enslavement and more than a century of white supremacy and stark discrimination in the distribution of social and economic goods—were in close alignment, as were their goals for social justice and beneficial goods in all matters of race. The historian Peniel Joseph offers a robust analysis of this alignment in his 2021 book The Sword and the Shield, arguing that Malcolm and King were at heart radical militants. Joseph’s analysis, however, overlooks the pathbreaking civil rights militancy of their older contemporary, Paul Robeson. This story offers a corrective.

Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were on similar revolutionary trajectories before their untimely deaths, as was Paul Robeson before a vengeful government and unforgiving mainstream media orchestrated his near erasure from the general public’s historical memory. The ninth story in this collection links Robeson, Malcolm, and King to each other and to the 21st century “Black Lives Matter” movement, “The 1619 Project” of The New York Times, and the juries that condemned the white murderers of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery in 2021 and 2022.

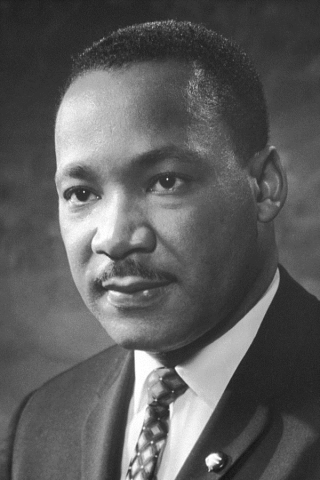

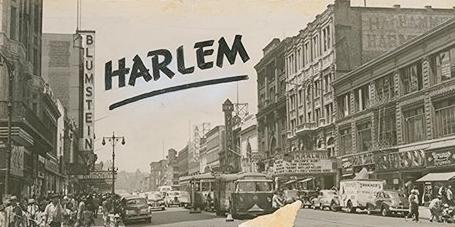

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Philadelphia

King made multiple visits to North Philadelphia and West Philadelphia. While he was a student at Crozer Theological Seminar in Chester, PA, 1948–1951, King audited courses in philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. From the mid-1950s to mid-1960s, he made several appearances at Convention Hall and Irvine Auditorium. King’s close friendship with Rev. William H. Gray II, pastor of North Philadelphia’s Bright Hope Baptist Church, made that church his most frequented Philadelphia venue. His most celebrated West Philadelphia event was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference-sponsored “Freedom Now Rally” at 40th Street and Lancaster Avenue, August 3, 1965. Commemorating this event are a state historical marker, mural, and MLK sculpture. At the time of this writing (fall 2022), the King mural is in jeopardy of being replaced by a developer.

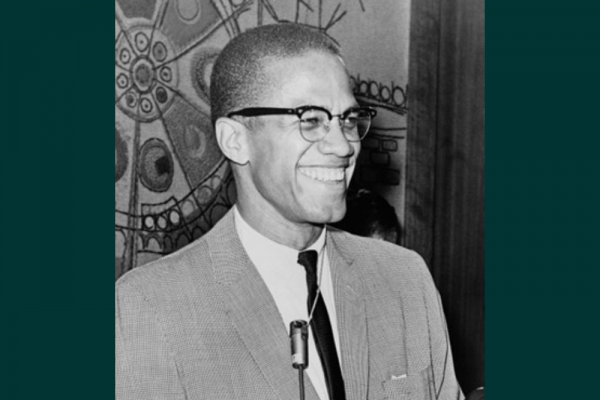

Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The conventional wisdom of civil rights historiography casts Malcom X as the militant avatar of Black Power and self-defense and King as the saintly prophet of nonviolent direct action. In his 2021 book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., the historian Peniel Joseph argues that these two men “represented dual sides of the same revolutionary coin and should not be viewed as warring ideological souls.” A noted historian of Black Power in America, Joseph presents a scrupulously detailed analysis and comparative biography to support this argument.

Joseph holds that their ideals and methods were converging in the first half of the 1960s as King took up the banner of “radical citizenship” in his militant confrontation with segregated northern and midwestern cities. Shaken by the murderous white violence leveled against civil rights demonstrators across Mississippi and Alabama in 1963 and 1964, Malcolm finally accepted King’s campaign for Black voting rights as a necessary step toward achieving his own goal of “radical Black dignity.” In the end, says Joseph, the two privately admired and inspired each other.

While Sword and Shield is a landmark contribution to the historiography of Black freedom struggles, Joseph’s comparative biography of Malcolm X and King nonetheless perpetuates a post-1960s trend among civil rights historians that obscures the militant campaign for human dignity and self-determination for all oppressed people bravely waged by Robeson and his close allies from the 1930s–1950s. In fact, Robeson is only mentioned once in Sword and Shield. Robeson’s biographers remark on the main Civil Rights Movement’s aversion to Robeson’s unrepentant allegiance to the ideals embodied in the founding of the Soviet Union, which he believed would someday be realized. Cold War exigencies may explain why King, his Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and other mainstream civil rights groups—the NAACP and CORE—chose to ignore Robeson.

Unlike Malcolm X and King, Robeson’s militant political agenda had no institutional base. Entering the 1960s, Malcolm was the de facto commander of the lower echelon of the Nation of Islam (NOI), and as such, a threat to Elijah Muhammad and his family’s leadership. King commanded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. From the mid-1930s to the 1960s. Although he had allies who were rooted in religious and cultural organizations, Robeson pledged allegiance only to his own conscience. In the 1960s, Malcolm and King gravitated toward causes that were focal points of Robeson’s earlier militancy.

King never publicly debated Malcolm, leaving that task to close allies such as Bayard Rustin. In November 1961, in the wake of the Freedom Rides to test the validity of the Supreme Court’s ban on racial segregation in travel facilities across the South, Rustin, acting as King’s proxy, debated Malcolm at Howard University. SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael had a front row seat at the debate. He recalled Malcolm’s public charge that King’s goal of racial integration was anathema to Black dignity as an “inflection point” in SNCC’s turn to Black nationalism. Joseph writes, “The Muslim leader’s talk of racial pride, political self-determination, and Black solidarity motivated a generation of young activists to imbibe large quantities of Black history, investigate the significance of African decolonization and reimagine the meaning of African American identity in Western culture.” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 118).

Debating another racial integrationist, James Farmer of CORE, in the spring of 1962, Malcolm, holding in view King’s civil rights campaign in Albany, Georgia, renounced integration in favor of separation. Notably, Malcolm, echoing Paul Robeson’s stance and predating Black Power, the 21st-century Black Lives Matter movement, and The New York Times 1619 Project, viewed Black enslavement and its Jim Crow legacy as integral to the nation’s founding and the driver of American capitalism. “We have been giving slave labor for 400 years and we’re not going to get sufficient repayment through any Jackie Robinsons [the Black athlete who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947] or Marian Andersons [the Black singer who violated a Jim Crow taboo by performing at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939] or a cup of coffee [referring to the student sit-ins to integrate Southern lunch counters].” Claiming to represent working-class Blacks’ struggles for collective Black dignity, he said, “I don’t think that an integrated cup of coffee is sufficient payment for 310 years of slave labor.” Joseph argues that despite their heated disagreements about political tactics, Malcolm and the civil rights activists shared the core value of “human dignity” as a goal (Joseph, Sword and Shield, pp. 124–125).

Malcolm advocates for Black self-defense; King goes to jail

The April 1962 police shooting of NOI member Ronald Stokes in Los Angeles was a turning point in Malcolm’s advocacy for Black self-defense and motivated his break with the NOI policy of eschewing political activism. Malcolm was inspired by Third World revolutionary activists, especially those who adopted guerilla tactics, accepting violence as sometimes a necessary means for building a just society. At this time, King rejected Malcolm’s project and continued to advocate for nonviolence in the struggle for Black equality and to lead civil rights activities within the existing political system. Events in Birmingham, Alabama, from spring–fall 1963, however, brought the two militant activists into closer alignment. Birmingham was a notoriously segregated city scarred by a history of anti-Black hostility and violence. Here King’s leadership of an Easter-season boycott of Birmingham’s white stores, in defiance of a court-ordered injunction, landed him in the city jail. Eight prominent white clergymen harshly criticized King for this and other demonstrations; King adroitly responded to their criticisms in his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

King’s campaign to desegregate Birmingham is notable for comparative purposes with Malcom X in two ways. First, in his “Letter,” King not only castigated the failure of the South’s white ministers, priests, and rabbis to declare before their congregations the moral righteousness of racial justice, he also contrasted the “horse-and-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter” in America to the “jet-like speed” of the movements for independence and self-determination then under way in Africa and Asia. An emotionally charged paragraph in “Letter from Birmingham Jail” relays as powerful and vindictive a condemnation of historic modes of white suppression of Blacks as one finds in Malcolm’s speeches short of his pre-Mecca hajj fulminations about “white devils.”

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.1

The year 1963 is exceptionally memorable, on the one hand, for the King-led March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August, which Malcolm X disparaged as peaceful kowtowing to whites; on the other hand, for the vicious white violence directed against Blacks in Mississippi and Alabama: the murder of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers in June, the Birmingham church bombing that killed four Black girls in September. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November of that year. In June the President had sent a forceful civil rights bill to Capitol Hill; Malcolm notoriously described the President’s death as “chickens coming home to roost” in a speech, “God’s Judgment of White America” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 168).

In 1964 Malcolm endorsed Black power at the ballot box, for the first time, to hold presidential candidates accountable. This signaled his willingness to work toward legislative changes to ensure Black voting rights—which was one of King’s signature goals. Elijah Muhammad did not agree. By that point, Malcolm was convinced that the Black vote was essential to achieving racial justice in America, and he envisioned Black power gains in the U.S. as a powerful impetus to Third World movements for “radical political self-determination, anti-colonialism, and human rights” (Joseph, Sword & Shield, p. 182). Yet he continued his advocacy for Black self-defense (preventive violence), which King continued to publicly condemn.

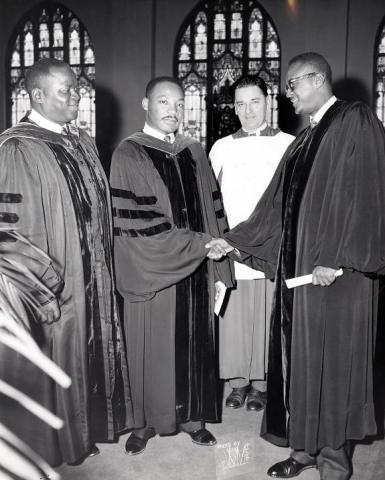

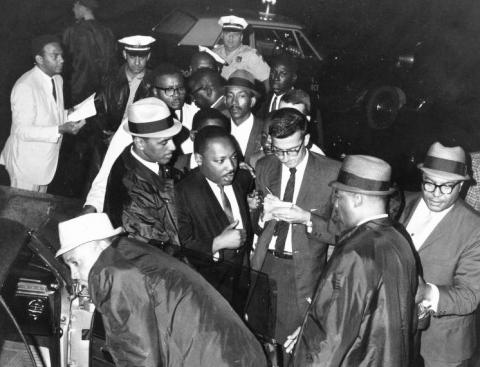

Malcolm X meets Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In March 1964, Malcolm and King met for the first and only time, at the U.S. Capitol. The occasion was the Democratic Party’s (ultimately failed) Senate filibuster of the 1964 Civil Rights Act; Malcolm and King exchanged greetings, shook hands, and smiled for photographers. Malcolm now regarded civil rights as part of a larger international struggle for human rights, while defending the morality and legality of self-defense.

In April, Malcolm undertook his famous hajj to Mecca, where he encountered the full range of the Muslim faithful, “from blue-eyed blonds to Black skin Africans.” “I have never before seen sincere and true brotherhood practiced by all colors together, irrespective of their color,” he wrote (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 188). Malcolm became committed to serving a global Black movement, “pan-Africanism”, for universal Black dignity, one founded on the religious tenets of orthodox Islam. An April–May tour of several post-colonial African nations followed his hajj; Malcolm wore a reddish-brown goatee in the style of orthodox Muslims, another affront to the Nation of Islam. The colors and dress of Africa inspired Malcolm’s vision of an “African-centered cultural renaissance” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 261).

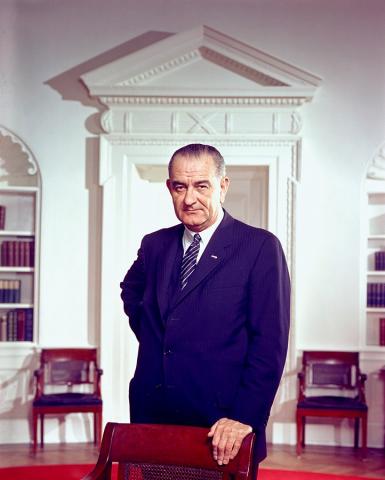

On the U.S. domestic front, the summer of 1964 was marked by police-incited race riots in North Philadelphia and Harlem; the KKK’s lynching of three civil rights activists in Neshoba County, MS (which drew national media attention only because two of the victims were northern whites); and the debacle of the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, NJ. The latter event marked the beginning of King’s disillusion with Lyndon Johnson; to King’s chagrin Johnson held an impromptu news conference intended to interrupt the broadcast of activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s pitch to have the delegates of the SNCC-organized Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) seated at the convention in lieu of the state’s all-white delegation. Confronted with the limitations of Johnson’s Great Society legislation, much of which the Eighty-Ninth Congress passed in 1964, albeit without an accompanying voting rights bill, King targeted Selma, AL for the voting rights campaign he would mount in that city in 1965.

King’s visit to Harlem in the stressful days that immediately preceded the 1964 riot and the horrific events in Mississippi had pushed him to the point that enough was finally enough, an argument he made in a speech in London in December declaring that the nation’s poor Black majority would never be free of the straitjacket of racial segregation without the political voice that was only achievable through the ballot box, and never truly free without a forging of Black citizenship that “would require ‘massive retraining programs, massive public works programs’ to provide jobs, education, decent housing, and ‘adequate health facilities’” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, pp. 216–217). Malcom shared King’s emergent radical view of economic justice as indispensable to racial justice—although Malcolm still refused to retrench on his advocacy of Black self-defense, and for that reason, King turned down several of Malcolm’s requests for meetings.

Malcolm X’s assassination

Malcolm’s assassination by NOI operatives on February 21, 1965 tragically terminated what might have become a friendship with King. An admiring essay King wrote following Malcolm’s death, where King first publicly acknowledged Malcolm’s deep religious faith and his political integrity, suggests as much. “King recognized the convergence between Malcolm’s struggle for Black dignity and his own quest for radical Black citizenship” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 233). Their only meaningful divergence was Malcolm’s refusal to abjure violence in defense of Black lives and property. They never reconciled their differences on this issue.

During the buildup to the SCLC’s voting-rights march from Selma to Montgomery, AL, Malcolm, just before his death, visited Selma, the site of demonstrations, as a gesture of outreach to civil rights groups. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, Alabama state troopers, assisted by Sheriff Jim Clark’s police, violently dispersed the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. In the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday,” Lyndon Johnson sent his Voting Rights Act to the Congress, which after passage in both houses, Johnson signed into federal law on 5 August 1965. Five days later, the Black neighborhood of Watts, in Los Angeles, erupted in fatal mayhem, flames, and looting. Now, King understood viscerally what he had only rationalized the previous December, that Black dignity and human rights had to be the core components of “radical Black citizenship.” While his analysis of “the depth and breadth of racial segregation, poverty, and anti-Black violence,” manifested horrifically in distressed urban neighborhoods like Watts, now more closely aligned him with Malcolm X, and while he understood that “the uprising in Watts represented one direction that the Black freedom struggle might pursue if nonviolence failed,” King was now intent on ramping up nonviolent protest to be a “peaceful sword” throughout America.

King, now more forcefully than ever before, called for massive civil disobedience to be used as a political tool in service of a Black revolution. . . . Watts gave King his clearest understanding to date that Black citizenship required the raw power to not only change hearts and minds but fundamentally alter power relations between Blacks and whites. This meant utilizing Black bodies to change the status quo of American race relations and make the beloved community a reality. (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 247)

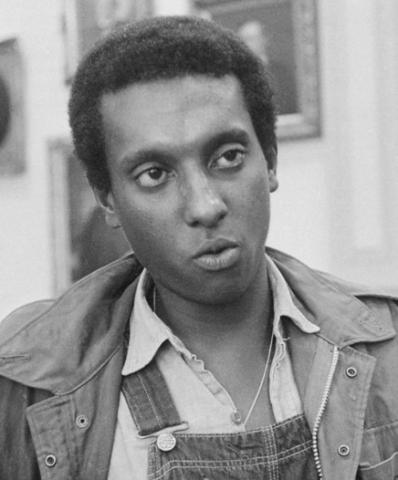

In 1966, the radical SNNC leader Stokely Carmichael took up Malcolm X’s mantle as the avatar of Black identity, self-determination, and political power—now evoked by the phrase “Black Power,” the title of Carmichael’s famous book with Charles Hamilton. As the year progressed, Carmichael joined with King in the latter’s 1966 nonviolent campaign for open (racially integrated) housing in Chicago, which triggered violent white resistance and exposed virulent anti-Black racism in the North.

Guns versus Butter

By 1967, America’s escalation of the Vietnam War and its threat to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs were uppermost in King’s mind: “guns and butter” were incompatible agendas. Carmichael was ahead of King on this issue, having condemned the war as racist and immoral in an August 1966 broadcast of Meet the Press; he encouraged Blacks to resist the draft. King broke his public silence on Vietnam in an emotional sermon at New York City’s Riverside Church, on April 4, 1967. Speaking as a “citizen of the world,” King connected the threads of his opposition to the war and hinted at his profound disappointment in Lyndon Johnson:

Since I am a preacher by calling, I suppose it is not surprising that I have seven major reasons for bringing Vietnam into the field of my moral vision. There is at the outset a very obvious and almost facile connection between the war in Vietnam and the struggle I, and others, have been waging in America. A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor—both black and white—through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings. Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated, as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war, and I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube. So, I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.

King lamented the disproportionate number of African American youth fighting and dying in Vietnam, fighting, he said, for liberties in Southeast Asia that were denied to them at home. He cited the shackles of enslavement that continued to bind African Americans of his generation, and he stipulated that Black violence in Northern ghettoes was understandable. King sketched Vietnam’s history in prescient terms, foreshadowing late 20th- and 21st-century historians’ understanding of terrible mistakes in the nation’s Southeast Asian policy. He called the war a “horrible, clumsy, and deadly game, with ominous consequences for the soul of America.”

This business of burning human beings with napalm, of filling our nation's homes with orphans and widows, of injecting poisonous drugs of hate into the veins of peoples normally humane, of sending men home from dark and bloody battlefields physically handicapped and psychologically deranged, cannot be reconciled with wisdom, justice, and love. A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.2

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s anti-war stance did not make him popular

After Riverside, King was persona non grata in the eyes of the Johnson administration, the mainstream media, and a majority of the American public, according to polls. He was criticized as being little different than Stokely Carmichael, who “scared the hell out of white folks” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 274). Indeed, Carmichael and King, the latter now the nation’s foremost antiwar activist, were united in their opposition to the Vietnam War. They were headliners at the nation’s largest antiwar rally the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam held in Central Park on April 15 with four hundred thousand demonstrators packed into the Sheep Meadow. From the park King and Carmichael marched arm-in-arm accompanied by most of these demonstrators to the United Nations. In a speech that followed Carmichael’s, King called for all military-age young men to seek conscientious objector status. On April 30,

King delivered his definitive anti-war speech [at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta]. . . . King praised Muhammad Ali’s controversial draft refusal as an act of moral courage. He spoke eloquently of Ali’s sacrifice “in order to stand up for what his conscience tells him is right,” as if commenting on his own path. At the conclusion of King’s sermon, Carmichael jumped up from the front-row pew to lead a standing ovation, the third round of applause during the sermon, which recognized the transformation of King from a preacher and movement leader into a revolutionary. . . . Martin loved Stokely and treated him like a younger brother. They bonded over their shared reputation as charismatic orators, mischievous sense of humor, and unapologetic love for Black people. Now, King and Carmichael shared a message against the war abroad for the sake of justice at home (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 275).

In the summer of 1967, King published Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, a book that found common ground with Carmichael on the importance of Black history, culture, and racial pride, yet took issue with the Black Power movement’s disregard of King’s vision of “a coalition of Negroes and liberal whites that will work to make both [national political] parties truly responsive to the needs of the poor.”3 Oakland’s Black Panthers, inspired by the late Malcolm X and Carmichael’s political organizing in Alabama, weren’t taking note of King when developing a ”revolutionary persona based on a ten-point program calling for a political revolution that necessitated grassroots organizing and guns” (Joseph, Sword & Shield, p. 279).

The disastrous July 1967 riots in Newark (disturbingly photographed by Life Magazine) and Detroit (the latter leaving 43 dead and over 300 injured) left King shaken. Whereas Carmichael called for an uprising of urban guerrillas to defend Black neighborhoods, King advocated for nonviolent demonstrations of an even greater magnitude. His proposed antidote to Black Power violence was the Poor People’s Campaign, which “would leverage the power of the poor through strategic political alliances with whites, Native Americans, Latino farm workers, and Black sharecroppers, who King dreamed would descend on Washington and unleash demonstrations in numbers too big to ignore” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 285).

Denouement

Five days after Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek another term as president, King was assassinated in the early evening of April 4, 1968 in Memphis, where he had come to march with striking Black sanitation workers. King was killed by a single bullet fired by an escaped white convict, James Earl Ray, as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in conversation with several close associates. King’s death unleashed rioting and political upheaval in 125 cities, including the nation’s capital, where 4,000 military personnel were sent to protect the White House.

It is important for the current generation of Americans to know that King at the time of his death was reviled and harassed by young Black nationalists. They lacked the experience King shared with Carmichael in the southern civil rights struggle, and the respect Carmichael accorded King. Hardly the Uncle Tom denounced by the young nationalists, King advocated for “radical Black citizenship that comprised a living wage, federally guaranteed income, decent and racially integrated housing and public schools, and a wholesale reconsideration of foreign and domestic policy. It meant leveraging America’s financial might on behalf of the poor, ending racism, and obliterating poverty and injustice through guaranteed economic benefits for all, especially those left out of an era of national prosperity. The very man booed in certain quarters as insufficiently radical now candidly admitted that ‘most Americans are unconscious racists’” (Joseph, Sword and Shield, p. 289).

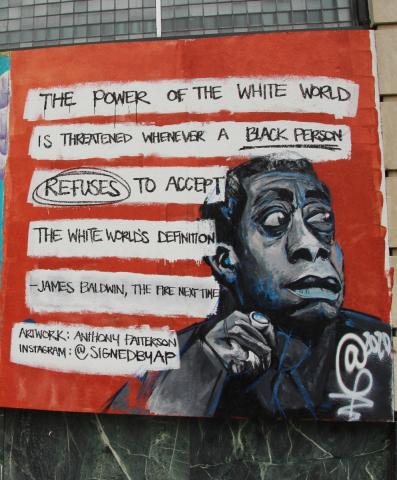

In 1972, James Baldwin, who was a close friend to both Malcolm and King, memorably wrote that while the two civil rights icons started from vastly different places in society, by the time of their untimely deaths their profound understandings of historically entrenched structural inequities—tracible to 300 years of Black enslavement and more than a century of white supremacy and anti-Black discrimination in housing, education, employment, transportation, healthcare, law enforcement, and voting rights—were in alignment, as were their goals for social justice and beneficial goods in all matters of race. Black dignity (Malcolm’s aim) and radical Black citizenship (King’s aim) were two sides of the same coin.

In November 1983, President Ronald Reagan, his earlier hostility to King notwithstanding, signed the bill that authorized King’s birthday as a national holiday. Today the holiday honors King’s memory as a day of national service. Though King came to be known as a peacemaker, and is often contrasted with Malcolm X, it is clear that King came to share many of his ideas. Both men owe a debt of gratitude to Paul Robeson, who laid the foundation for both civil rights leaders to pursue change.

1. “Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Atlantic, August 1963, originally published under the headline “The Negro is Your Brother,” reprinted in the magazine’s celebration of MLK’s legacy, 4 August 2018, accessed from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/02/letter-from-a-birmingham-jail/552461/, 16 May 2022.

2. Martin Luther King Jr., “Beyond Vietnam—A Time to Break Silence,” delivered at Riverside Church 4 April 1967, accessed from American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkatimetobreaksilence.htm, 20 February 2022.

3. Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go from Here? Chaos or Community? (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), p. 50.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |