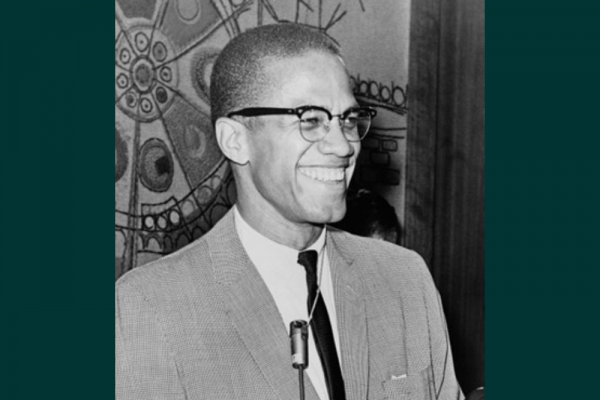

One of many images of Paul Robeson in the New York Public Library Digital Collections, a trove for researchers of the New York Theater.

Paul Robeson was the best known African American of the first half of the 20th century. He was famous as an All-American football player, the world’s finest bass-baritone singer of his time, a pioneering black theatrical and screen actor, and a tireless political activist. He advocated throughout the world for socialism, anticolonialism, and human rights for all oppressed peoples, irrespective of race, religion, or ethnicity. He spent the final decade of his remarkable life in West Philadelphia at 4949 Walnut Street.

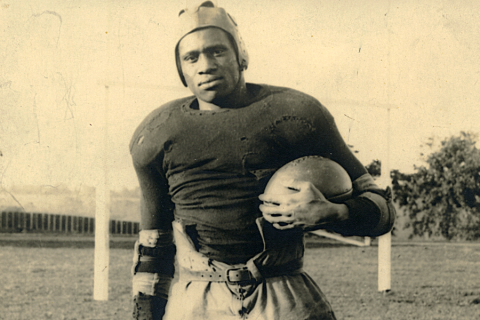

Paul Robeson was born in 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, to a large family marked by tragedy and constrained by the racial mores of northern Jim Crow. Inspired by his indomitable father, a pastor of shifting religious allegiances, Paul surmounted these obstacles to graduate at the top of his class from Rutgers College, achieve All American status as a football player, and develop a remarkable talent as a bass-baritone singer. By the time he was thirty, he held a law degree from Columbia University and was a rising international star as a singer of Black spirituals and actor for stage and screen.

Paul Robeson was the world’s most famous African American in the first half of the twentieth century. Part I of this series looks at Robeson’s background and his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable bass-baritone singer and pioneering African American actor for stage and screen.

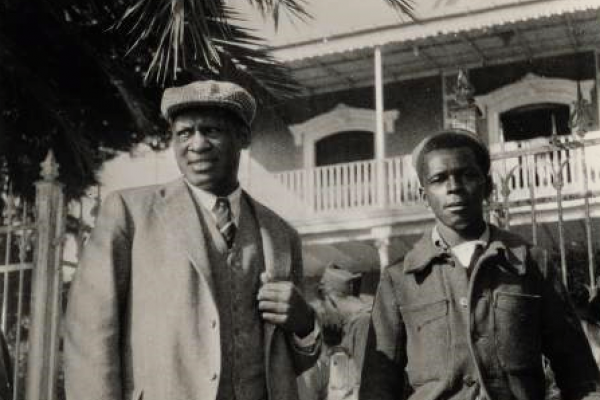

At age 15 in 1860, Paul Robeson’s father, William Drew Robeson (1844–1918), was a fugitive from enslavement on a farm in Martin County, North Carolina. William trekked north to Pennsylvania, found work as a common laborer in the Union Army, and after the Civil War, undertook theology studies at the all-Black Lincoln University, near Philadelphia. In 1878 he married Maria Louisa Bustill, a teacher at Philadelphia’s Robert Vaux School and a member of a prominent family of mixed African, Delaware Indian, and English Quaker descent. By the time their son Paul Leroy Robeson was born on April 9, 1898—the seventh of nine children, five of whom survived infancy—William was pastor of the all-Black Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church in Princeton, New Jersey. In spiritual matters, Princeton was a Jim Crow town, formed by the all-white university that shared its name. In 1846, whites in the First Presbyterian Church had forced their Black members to form their own church, which William subsequently led.

Judged insufficiently servile by Witherspoon’s white sponsors, William was forced to resign his pastorate in 1901. Another tragedy struck three years later: his wife, Louisa, an invalid in poor health, died from burns endured when a stove coal set her dress aflame. At age six, Paul Robeson was a motherless child.1

Paul and his older brother Ben were the only Robeson children to accompany their father to Westfield, New Jersey, where William worked for a time as a coachman and ash hauler. In 1907, at age 62, he managed to organize an A.M.E. Zion church in Westfield, whose white citizens were kinder than Princeton’s and helped care for Paul and Ben. In 1910, with Ben off to Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith University) in Charlotte, North Carolina, William established himself as pastor of an A.M.E. Zion parish in Somerville, New Jersey.

Motivated by his demanding father, a master of oratory and English diction, young Paul excelled at Somerville High School, where he was among a handful of Black students. Paul earned accolades as a public speaker and champion debater. He was an exceptional athlete, especially ferocious as a football player. Despite the efforts by Somerville’s racist principal, Mr. Ackerman, to thwart him, Paul won an academic scholarship to Rutgers College, where he arrived in 1915—only the third African American to formally attend this (at the time private) college since its founding in 1766. As New Brunswick was a segregated town, Paul resided in the town’s Black community. Standing 6’2’’ and weighing a muscular 196 pounds, Paul won applause and respect from white students, first as an All-American defensive end on the school’s talented football team, hailed by many sportswriters as the nation’s best player; second as a gifted scholar, debater, and singer.

Yet intimacy with whites was not in his cards. As Martin Duberman, Robeson’s foremost biographer, has written:

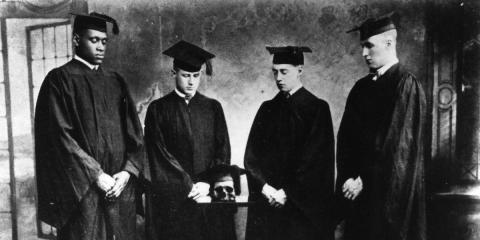

Robeson maintained such a consistently high grade average in his course work that he was one of four undergraduates (in a class of eighty) admitted to Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year. A speaker of exceptional force, he was a member of the varsity debating team and won the class oratorial prize four years in succession. His bass-baritone was the chief adornment of the glee club—but only at its home concerts; he was not invited to be a “traveling” member, and at Rutgers sang only with stipulation that he not attend social functions after the performance.2

Paul’s studies were literary and classical. The prestigious Cap & Skull Society selected him as one of four men best representative of the school’s ideals; he was valedictorian of his graduating class, and he delivered the 1919 Commencement Oration, where he spoke about American race relations in an optimistic, conciliatory tone—a stance he would repudiate in the 1930s.

In the summer of 1919, Paul moved from New Brunswick to Harlem in New York City, where he shared an apartment on 135 Street. While attending law school at Columbia University. Harlem, “the Negro capital of the world,” was the major northeastern terminus of the Great Migration of southern Blacks fleeing Jim Crow in search of freedom and jobs. It was also a hub for returning Black veterans from World War I. That fateful summer Harlem was spared the white-supremacist viciousness that ruthlessly claimed Black lives and property in Chicago’s 1919 race massacre. Such violence was in Harlem’s future, however.

It's difficult to imagine how Paul managed to balance the huge demands on his time and energy. For example, to help pay his law school tuition, he played (well-paying) professional football for the Akron Pros and for the Milwaukee Badgers. It was the winter of 1920–21 when Paul met and courted his future wife and business manager, Eslanda Goode, known to her friends as “Essie,” who worked as a technician in the surgery lab at New York’s Presbyterian Hospital.3 Essie and Paul wed August 17, 1921 (their son, Paul Robeson Jr, was born in Nov. 1927). Essie continued to work at Presbyterian Hospital while Paul balanced his law studies with part-time professional football and singing recitals.

Robeson received his law degree in the winter of 1923. He found employment as the only Black attorney in the law office of a Rutgers alumnus in New York. Robeson soon quit this job at Stokesbury and Associates at Law and his law career altogether when a stenographer refused to take dictation from a Black man; she purportedly used a racial epithet. Fortuitously during his brief employment at the law firm, Paul had taken various roles at Harlem’s storefront theaters, learning the fundamentals of acting. The musical Taboo had a short booking on Broadway and played briefly in England during the summer of 1922 with Paul as the male lead. The English version was called Voodoo. It was the story of a wandering Black minstrel, Tim, who, through his transformation as an African Voodoo King, magically removes a curse on the mute granddaughter of the plantation’s mistress and brings rain to the drought-stricken land.

In 1923 Paul leaped at the offer of a role with the avant-garde Provincetown Players as Jim Harris in Eugene O’Neil’s new play All God’s Chillun Got Wings, which opened in New York in 1924 as one of the repertory theater’s alternating plays. Chillun’s treatment of an interracial marriage undermined by hostile social forces provoked a backlash among white politicos.

The O’Neil play best suited to Paul’s immense talents was The Emperor Jones, with Paul in the role of Brutus Jones, a Pullman porter whose criminal activity lands him in prison and hard labor breaking rocks, which he escapes by killing a guard. Reinventing himself, Jones becomes the emperor of an island in the West Indies whose corruption provokes a revolution that culminates in his death by suicide as drumbeats from the jungle boom offstage.

Incredibly, Robeson had to master two roles simultaneously—Jim in Chillun, Brutus in Emperor Jones—with Essie rehearsing him relentlessly. When the Black press criticized him for playing Emperor Jones, which they said pandered to negative stereotypes of African Americans, Robeson replied that his commanding performance as a tragic Black protagonist was a big step above the lackey “Sambo” roles traditionally assigned to Black actors. He considered it a step toward his ultimate goal of portraying authentic Black characters. Chillun and Emperor Jones had profitable runs in alternate weeks in 1924.

After a performance of Emperor Jones, the young sculptor Antonio Salemmé approached Robeson with a lucrative financial offer to pose for the artist. Intermittently for the next two years, Paul sat for Salemmé. A giant statue of Robeson, completed in 1926, stood for a year in the Palace of the Legion of Honor; in 1930, the Philadelphia Art Alliance rejected Salemmé’s offer of the statue, as the executive committee feared a violent white backlash over the public display of a naked Black man. “We sculptors don’t sell many statues in Philadelphia,” Salemmé told reporters.4

The year 1924–25 saw the birth of the Harlem Renaissance, with Robeson and his accompanist and arranger Lawrence Brown, whom he had met in London, counting themselves among the district’s Black cultural luminaries. The Robesons cultivated deep friendships with Walter White of the NAACP and James Weldon Johnson and his wife, Rosamond. Drawn to the historical roots of contemporary Black culture, he adapted his splendid bass baritone voice to interpret Negro spirituals, which bonded him to the Johnsons. Their circle also included white artists and literati. Entranced by Paul’s singing, one of the Harlem Renaissance’s impresarios, Carl Van Vechten, introduced the Robesons to his inner circle of friends which included, among others, the composer George Gershwin and the writer Theodore Dreiser.

In the 1870s the Fisk Jubilee Singers sang spirituals and folk songs composed by African Americans as part of their fund-raising tours for Black education. After they disbanded, the only exposure whites had to African American music was black-face minstrel shows and reviews that mocked the Black experience. Robeson’s first recitals featuring African American spirituals and folk songs were at Boston’s Copley Plaza and New York’s Greenwich Village in the fall of 1924.

Yet racial prejudice was always an obstacle; for example, Robeson, despite his celebrity, was denied entry to every restaurant between Greenwich Village, where he rehearsed Jones, and Penn Station. From 1927 to 1939, Paul and Essie would maintain their primary residence in England, which they found to be, in Paul’s words, “warm and friendly and unprejudiced.” They enjoyed the company of London’s artistic and literary giants; they also imbibed the culture of Ernest Hemingway’s Paris. Here Paul’s rise to international stardom was meteoric on the strength of concert performances (with Larry Brown) that included European folk songs, classics, and popular ballads. During his productive European sojourn, he occasionally returned to the U.S. to record spirituals and for concert tours, including a fall 1929 Carnegie Hall debut. In the early years of his expatriate sojourn, he also acted on Broadway.

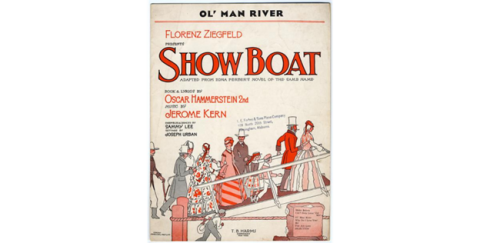

In 1928 he performed on the London stage as Joe the Riverman in the Jerome Kern musical Show Boat, where he sang “Ol’ Man River,” a plaintive song that ran throughout the show. The show was a huge success and a financial boon for Paul and Essie. The Prince of Wales invited Paul to give a command performance of “Ol’ Man River” at Buckingham Palace. Paul and Essie’s new circle of friends and admirers included the cultural icons of progressive Britain—H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and Rebecca West—as well as left-wing members of Parliament.

Marie Seton, Robeson’s British biographer, writing years later, recalled her experience of Show Boat:

Like many other Londoners, I went to see “Show Boat” soon after it opened. [There was] no dramatic build-up for the entrance of the new star, Paul Robeson. The scene shifted from the steamboat to the wharf. Suddenly one realized that Joe the Riverman was Robeson, the silent figure endlessly toting bales of cotton across the stage. [He] filled the whole theater with his presence. Paul Robeson sang about the flowing Mississippi, and the pain of the black [sic] man whose life is like the eternal river rolling toward the open vastness of the ocean. The expression on Robeson’s face was not that of an actor. The pathos of Robeson’s voice called up images of slaves and overseers with whips. How had a man with such a history risen? A most startling quality appeared in Robeson as he accepted the applause. He was visibly touched and yet remote. He seemed to have no greed for applause and he appeared to be a man stripped of mannerisms. The story of romance on a showboat plying the Mississippi suddenly moved into the foreground and Joe, the son of slaves, went back to toting bales of cotton. I have never forgotten the bend in Robeson’s back. It was full of strength, yet it expressed a sorrow which seemed to know no end.”5

1. Part I of Paul Robeson Jr, The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898–1939 (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), is titled “Motherless Child.”

2. Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography (New York: New Press, 1989), 24.

3. For West Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania readers, it’s worth noting that Raymond Pace Alexander, a law school classmate of Robeson’s, later a Philadelphia judge, claimed that he introduced the couple when they were his guests on a voyage on the Hudson River. Alexander would marry Sadie Tanner Mossell, the first African American woman to practice law in Pennsylvania and to earn a Ph.D. in economics, while at Penn; she is the namesake of West Philadelphia’s University of Pennsylvania–Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Partnership School. Of further local interest, Paul’s aunt Gertrude, on his mother’s side, married Nathan F. Mossell, the first African American graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School.

4. Reported in Duberman, Robeson, 69.

5. Marie Seton, Paul Robeson (London: Dobson Books, 1958), 43–44, cited in Robeson Jr., Artist’s Journey, 1898–1939, 151.

A Note on Sources: Martin Duberman’s 800-page Paul Robeson: A Biography expertly charts the course of Robeson’s remarkable life and career and remains the single best and most cited Robeson biography. With Duberman’s careful attention to detail, his book is close to being a definitive biography, notwithstanding the 35-year time lag between its date of publication, 1988, and 21st-century medical advances and the contemporary Black Lives Movement. For my story collection, I have condensed and freely drawn from Duberman what I regard as the essentials of his narrative. Though limited as a historical study that adds to what Duberman describes as the turning points in Paul Sr.’s life, Paul Robeson Jr.’s two-volume biography, The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898–1939 and Quest for Freedom, 1939–1976, provides new, unvarnished details of Eslanda Goode Robeson’s tribulations as Paul’s lifelong business partner and financial manager, and her stressful marriage to Paul amidst his many extramarital affairs. Both Duberman and Paul Jr. are useful guides to Paul Robeson’s 1958 statement of beliefs, Here I Stand, from which I have quoted directly. A biography notable for its succinct identification of the dominant themes in Robeson’s melding of his artistry and radical political activity is Gerald Horne’s The Artist as Revolutionary. The most recent biography at this writing (fall 2022) is 2020’s Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson, skillfully illustrated by Sharon Rudahl and edited by Paul Buhle & Lawrence Ware. This imaginative book interprets Robeson for 21st century audiences.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

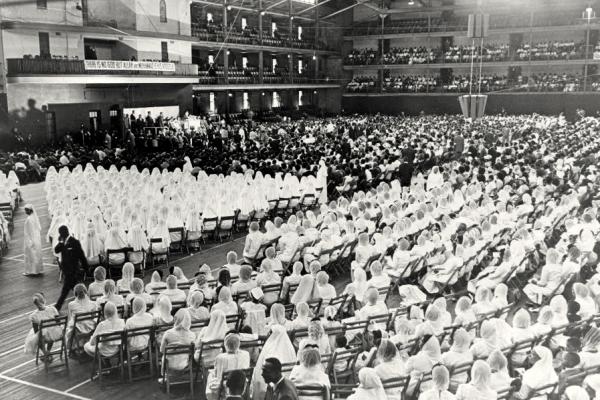

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |