Mill Creek’s Lucien E. Blackwell Homes

At the turn of the Millennium, Mill Creek Homes was in a state of neglect and disrepair. The project’s replacement would be the vibrant and radically different Lucien E. Blackwell Homes.

At the turn of the Millennium, the Mill Creek neighborhood was beset by population loss, building abandonment, graffiti, and drug-related crime. A traumatizing mass shooting would lead to a radical reconceptualization of public housing and a new round of urban redevelopment. Stressed by social ills and mismanagement, Mill Creek Homes was in a state of neglect and disrepair. The project’s replacement, begun in the first decade of the new century, was suburban-style Lucien E. Blackwell Homes. The Public Housing Authority’s criteria for selecting eligible residents would disqualify chronically poor families.

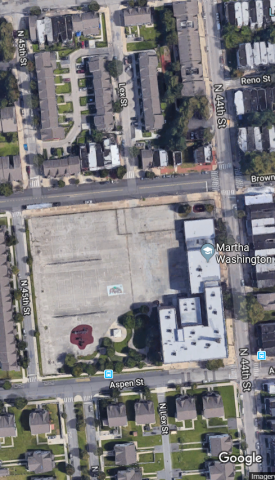

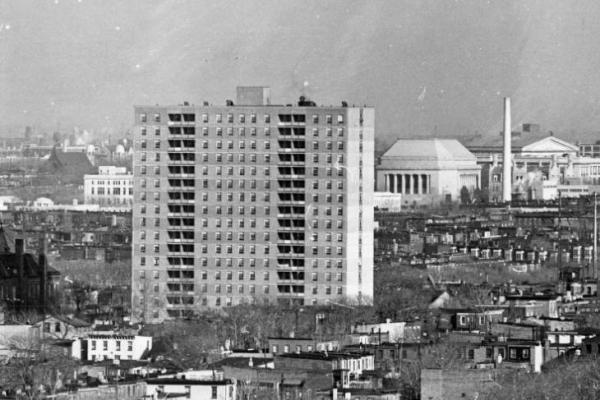

Mill Creek Homes, a public housing project with 444 total units, stood for a half-century in the Mill Creek neighborhood east of the Sulzberger Middle School between Fairmount and Aspen avenues. When completed, Mill Creek Homes consisted of three high-rises and two- and three-story low rises—a total of 444 total units, with 100 percent African American occupancy. At the turn of the Millennium, Mill Creek Homes was in a state of neglect and disrepair. The project’s replacement would be the vibrant and radically different Lucien E. Blackwell Homes.

Background

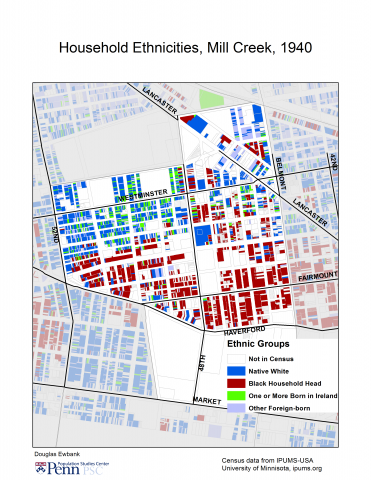

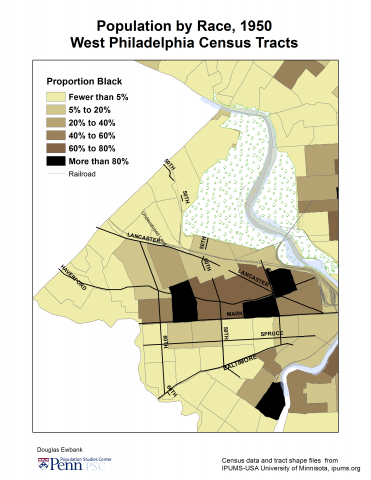

Named for its creek—since the late 1880s an underground sewer—the Mill Creek neighborhood covers about one square mile between Girard and Haverford avenues, 44th and 52d streets. The single U.S. census tract in which the neighborhood was tucked was majority black in 1940 and large-majority black (roughly 73 percent) in 1950. By 1960, when two census tracts enveloped the neighborhood, the eastern and western halves were 94-percent and 85-percent black, respectively. The black proportion of Mill Creek’s population would reach 99 percent in the eastern half and 96 percent in the western half by 1980—percentages that would remain relatively stable into the new Millennium.[1]

Instability, however, was evident in the neighborhood’s loss of population: down from an estimated 15,668 in 1950 to 7,015 in 2000 (figures based on census tract calculations, hence rough approximations), a loss of more than 7,500 over the half-century. The 1950s were marked by the outmigration of more than 2,300 whites in Mill Creek—a precipitous drop from 27 percent of the Mill Creek population to less than 11 percent and a loss that would never be recouped. Between 1990 and 2000, it was blacks who left Mill Creek: their numbers declined 25 percent. In the eastern half of neighborhood, the location of Mill Creek Homes, vacant housing rose from an already high 15.7 percent in 1990 to 23.9 percent in 2000, compared to the citywide rate of 4.7 percent in 2000.

By the turn of the Millennium, the neighborhood was beset by population loss, building abandonment, graffiti, and drug-related crime and violence. The Philadelphia Inquirer described it as “a neighborhood of extremes—well-kept rowhouses with flowers on the porch line one block, while filthy vacant lots litter the next.”[2] Philadelphia’s crack-cocaine crisis had a deadly impact here at the turn of the Millennium and spelled the end of Mill Creek Homes, a project depicted in the local media as crime-infested and deteriorating.[3]

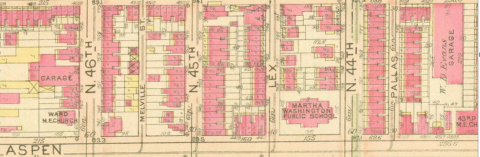

A traumatizing mass shooting would lead to a radical reconceptualization of public housing and a new round of urban redevelopment in Mill Creek. The media labeled this horrific incident the “Lex Street Massacre.” Designated for major redevelopment in the aftermath of the killings were the blocks bounded by Markoe and 44th streets, Aspen and Fairmount avenues. The suburban-style Lucien Blackwell Homes would replace the modernist Mill Creek Homes, whose elevator towers and old low-rise units were demolished.

“Lex Street Massacre”

Photographs show a row of badly deteriorated abandoned houses on Lex Street, which intersects with Aspen Street opposite Martha Washington Elementary School. (The cruel irony of this juxtaposition would not be noted in media reports.) The house at 816 N. Lex St. was a crack house. On the night of 28 December 2000, seven people died and three were wounded in this abandoned rowhouse in what the media called the worst mass murder in Philadelphia’s history. A police officer on the scene would later testify in court: “I noticed there were eight to 10 bodies on the scene. It’s probably one of the worst things I ever saw.” [4]

In the summer of 2000, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, “squatters seized the house and turned 816 N. Lex St. in a 24-hour drugstore. Downstairs, teenage crack dealers paid $25 a day to a squatter landlord to sell their wares. Upstairs, older crack smokers used bedrooms for sex and socializing.”[5] Ten people were in the house on 28 December. They were “lined up on the dining-room floor and shot. Seven bled to death.” Four of the seven were teenagers. The killings were described as “execution style.” The bodies, six men and one woman, lay in a circle around a kerosene heater. The age range of the victims was 15–54.[6]

City bulldozers leveled 57 abandoned houses in the neighborhood, including, on 7 June 2001, 816 N. Lex St. and most of the other houses on the 800 block.[7] Four black male suspects were charged with the murders and were held for 18-months without bail while homicide detectives and prosecutors tried to find hard evidence to prove their case. The investigators believed a small-time turf war for control of the crack trade in the blocks around Lex Street had set the stage for the killings. Their leads, however, were circumstantial and eventually were dead ends. On 10 July 2002, the day the trial was scheduled to begin, District Attorney Lynne Abraham dropped the charges.

Prosecutors’ case against [the four men charged with the crime] was never seen as strong—no physical evidence tied them to the killings at 816 N. Lex St. There is no DNA or fingerprint evidence, and police never recovered the three murder weapons. Instead police made the arrests after eliciting a confession from Lewis. But defense lawyers have argued that police coerced Lewis into making a false confession after an interrogation.[8]

A new line of investigation was undertaken. And it pointed to the guilt of a different quartet of men who would be charged with the killings. Two were the brothers Dawid (also known as Dawud) Faruqi and Khalid Farqui. This time the police had a weapon, a semiautomatic Glock pistol. And a different motive had emerged: The slaughter in the crack house arose from a disputed car deal. According to the police affidavit of the interrogation of Shihean Black, who, apparently uncoerced, confessed to his role, the crime bizarrely unfolded as follows:

Black said he had traded a black Chevrolet Corsica and $300 for victim George Gibson Porter’s gold Dodge Intrepid, according to the police affidavit. When the clutch on the Corsica “went bad,” Porter wanted his Intrepid back, Black told the detectives. In the meantime, Black had traded the Intrepid to Dawid Faruqi for a Glock semiautomatic pistol, and Porter had argued with Faruqi over the car. The night of the killings, Black said in his statement to the police, Dawid Farqui knew where Porter, who was 18, and his associates were. The Faruqi brothers, Black and [Bruce] Veney then drove to the Lex Street rowhouse, donned masks, and corralled the victims. But then—according to Black’s statement—Dawid Faruqi’s mask fell from his face, and he said: “We’ve got to kill these (obscenity). They know where I live. I’ve got kids. Black said that Faruqi began shooting, and that he and the other men joined in.[9]

The assistant DA who headed the prosecution’s team focused on the Faruqi brothers as the primary instigators of the murders. The two were implicated in other violent crimes unrelated to Lex Street, public knowledge of which gave the lead prosecutor considerable heft to single out the brothers for a death-penalty trial. The motive, he said, was “robbery, revenge, and retaliation” for the insult perceived by Porter’s demand for the return of the Intrepid. The 13-day trial concluded with a verdict of guilty against the Farquis. For their part, Black and Veney plea-bargained with the DA’s office for prison sentences to avoid a death-penalty trial; Black received seven consecutive life sentences without parole, Veney 15-to-30 years in prison.[10]

In the end, the Farqui brothers managed to avoid the death penalty by admitting their guilt and giving up their right of appeal and their right to request a pardon, according to the “lengthy written agreement by prosecutors.” In exchange, each brother received seven consecutive life sentences, with an additional 365 years tacked on. “This puts to an end the possibility that these men will ever walk the streets again,” said the DA Office’s homicide chief in an extravagant understatement.[11]

The “Lex Street Massacre” left longstanding open wounds in the Mill Creek neighborhood, even as the events of the night of 28 December 2001, unlike the 1985 police action against MOVE in the Cobb’s Creek neighborhood, receded in the wider public’s memory. “Raw, bitter” emotions remained “exposed.” “Even after seven years, long after the dead have been buried, the dilapidated rowhouses on Lex Street rebuilt and the media refocused on a daily dose of fresh murder and mayhem, there has been little closure for the victims at 816 N. Lex St.”[12]

The “Lex Street Massacre” was the signal and proximate cause for a sweeping urban redevelopment initiative by the Philadelphia Housing Authority in Mill Creek, the dominant component of which was Lucien E. Blackwell Homes.

Lucien E. Blackwell Homes

In 1993, the Clinton administration created the Hope VI housing program in the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The aim of this FHA program was to replace high-density elevator apartment buildings with affordable lower-density mixed-income homes that would be owned by their occupants. Though many working-class blacks qualified for partially subsidized mortgages through HOPE VI, and, later, through President Obama’s America’s Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), most low-income blacks couldn’t afford the new mortgages and, perforce, had to resettle in one of the city’s terribly poor neighborhoods.[13]

In the mid-1990s, Philadelphia began to take advantage of HOPE VI, which was overseen at HUD by the Philadelphia planner Ed Bacon’s daughter, Elinor Bacon[14], “demolishing the oldest public housing units, which had embodied the worst of slum conditions.”[15]

In the early 2000s, the Philadelphia Housing Authority followed HUD’s lead: “The goal is to establish mixed-income neighborhoods where severely distressed housing developments formerly existed.”[16] In other words, “to avoid creating the economic ghettos of the past.”[17]

The PHA’s “New Urbanism” program would restrict assisted homeownership to households earning no more than 80 percent of the city’s median income. Eligible participants would not have a serious felony on their record. Home-seekers of greater means could purchase the PHA’s comparatively inexpensive single-family homes—for example, “a new $155,000 two-story, three-bedroom home with an indoor garage on Brown Street, near 45th”— though without mortgage assistance from the PHA. There was also an income floor—$21,000 in 2007—which disqualified the chronically poor from participation.[18]

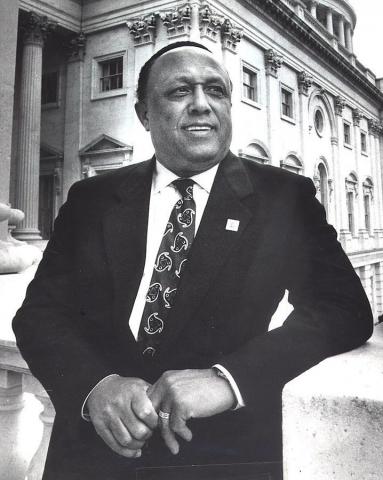

Launched in 2005, Lucien E. Blackwell Homes memorialized the West Philadelphia politician Lucien E. Blackwell (1931–2003). Blackwell was by turns a union leader, a state representative; a “vibrant” 16-year member of the Philadelphia City Council (1975–91), where he was known as “Lucien the Solution”; and U.S. House representative, elected to complete the term of William H. Gray III (1992), then elected to a full term in the House (1993–95). After losing his House seat to Chaka Fattah in 1995, Blackwell chaired the board of a debt-collection agency.[19]

Blackwell, a former Army boxing champion and Korean War veteran, was a towering figure in City Council. A longstanding union leader and old-style ward politician who doled out patronage to his supporters, Blackwell is recalled as a staunch champion of the working class, minorities, and homeless. Yet his “firebrand oratory” and confrontational personality made enemies of Philadelphia’s middle-class reformers, who orchestrated his defeat in the city’s 1991 Democratic mayoral primary, an election won by Ed Rendell. As mayor, Rendell’s neoliberal agenda—union-busting, privatization of social services, and tax abatements for corporate investments in City Center—largely ran counter to Blackwell’s neighborhood priorities and constituent-services orientation.[20]

The PHA built Lucien E. Blackwell Homes in multiple phases: groundbreaking took place in 2003; the first homes were sold in the fall of 2007 and the last ones were constructed in 2011. The total price tag for the 17-block revitalization was about $200 million.[21]

Replacing elevator towers and old low-rise units, the PHA “has built low-rise, low-density homes that mimic the city’s traditional rowhouses and twins, right down to their decorative Victorian cornices and wood-railed front porches. They come with amenities that previous public housing tenants never imagined, such as air-conditioning and dishwashers.” On 45th Street, a not-atypical house (priced at $115,000) “gains its character from its asymmetrical façade. The front door is announced by a covered portico supported by white Doric columns. The living room and master bedroom are thrust forward slightly and marked by a protruding two-story bay.”[22] Perhaps unsurprisingly given the quality of Lucien E. Blackwell Homes and the project’s selectivity of home buyers and renters, the area around the homes saw a 29 percent reduction in major crime in the first decade of new Millennium.[23]

Carl Greene

He was executive director of the PHA from 1998 to 2010. During his controversial tenure, Greene and his staff oversaw more than $1.6 billion in funds for redeveloping public housing in Philadelphia. Greene championed the “New Urbanism” design concept that inspired new low-rise, low-density projects like Lucien E. Blackwell Homes. While Greene is properly credited with the development of six Philadelphia sites that incorporate New Urbanism ideas, his tenure as the city’s housing czar was clouded by accusations of unethical and unprofessional behavior, including, most seriously, repetitive charges of sexual harassment.[24]

PHA’s board of directors fired Greene on 23 September 2010. Undertaking an investigation of issues raised by Greene’s conduct and what it regarded as “out-of-control” spending at PHA, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) demanded the resignations of the PHA board, among whose members was West Philadelphia’s City Council representative, Jannie Blackwell, Lucien Blackwell’s widow, holder of her husband’s former Council seat since 1992, and a “staunch supporter” of Greene. HUD officials were outraged by the revelation that “PHA secretly settled three sexual harassment complaints for $648,000.” And it appears that the department held the PHA board in part responsible for a failure of oversight.[25]

A Note on Public Housing Vs. Poverty

According to an extensive 2018 study of Philadelphia poverty by the Pew Charitable Trusts, “more than a quarter—about 400,000 people—live below the poverty line, which is about $19,700 a year for an adult with two children at home.” Although the study does not directly address public housing, its findings indirectly show that the city’s public housing reforms, and public housing in general, have not uplifted, or for that matter even touched, the large majority of the chronically poor. Startingly, “4 out of 5 poor households in Philadelphia lived in private-market housing with no rent subsidies in 2013, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Housing Survey. Of those households, nearly all were spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent, mortgage, and utility payments, and 80 percent were devoting at least 50 percent to such expenses.”[26]

[1] Population and housing statistics for this article are drawn from U.S. decennial censuses, 1940–2010, https://www.socialexplorer.com/explore-maps.

[2] “’Where Everybody Worked,’ the Trade Turned to Drugs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 23 July 2001. Investigative reporters at the Inquirer published a three-day series of articles on the shooting, providing details about the victims, the shooters, the drug activity at the house, and the subsequent arrests of four alleged perpetrators. These articles were based on evidence collected during the initial discovery period by police investigators and city prosecutors.

[3] Solomon Jones, “Crackup on Lex Street,” Philadelphia Weekly, 14 February 2001; for more recent social media on this subject, see “Buildings Then and Now: From Horror to Hope on Lex Street,” http://ww.phillyliving.com/blog/buildings-then-and-now-lex-street-from horror-to-hope.html.

[4] “Officer Describes Lex St. Killing Scene,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 February 2004.

[5] “’Where Everybody Worked,’ the Trade Turned to Drugs.”

[6] “Life Led 10 People into a Crack House,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 July 2001.

[8] “D.A. Drops Lex St. Murder Charges,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 July 2002.

[9] “Lex Street Killings Tied to Car Dispute,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 27 November 2002. In his statement, Veney said that he was the driver, that he was unarmed and when he heard the shots he was outside the house. The vehicle was a Chevrolet Blazer.

[10] “Brothers Are Found Guilty in Lex St. Killing,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 March 2004.

[11] “Two Brothers Admit to Lex St. Massacre, Get Life Sentences,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 9 March 2004.

[12] Annette John-Hall, “Reconciliation on Lex Street,” editorial, Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 September 2007; “18 Years after ‘Lex Street Massacre,’ City’s Biggest Mass Killing Is Remembered,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 December 2018.

[13] Much of the criticism of HOPE VI— the program left poor people out in the cold—targets the Chicago Housing Authority. See, for example, Pauline Lipman, The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City (New York: Routledge, 2011).

[14] Gregory L. Heller, Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 235.

[15] Roger D. Simon and Brian Alnutt, “Philadelphia, 1982–2007: Toward the Postindustrial City,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 131 no. 4 (2007): 395 – 444, quote from p. 437; Anonymous, “New Development Replaces Old Style Housing,” Journal of Housing and Community Development; Washington 61, no. 2 (2004): 13.

[16] Philadelphia Housing Authority, Moving to Work: Year Seven Report (Philadelphia: PHA, 2008), 34.

[17] Inga Saffron, “Low-Rise, High Hopes,” column, Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 April 2005.

[18] “SAFE HOUSES,” Philadelphia Daily News, 19 February 2008; “Open House Attracts Crowd at PHA’s Blackwell Homes,” Philadelphia Tribune, 11 November 2007.

[19] “Lucien Blackwell, Fighter for the Working Class, Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, obituary, 25 January 2003; “Lucien Blackwell,” https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Blackwell.

[20] Blackwell obituary; Timothy P.R. Weaver, Blazing the Neoliberal Trail: Urban Political Development in the United States and the United Kingdom (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 209–42.

[21] “PHA Opens New Public Housing in Mill Creek,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 April 2011.

[22] Saffron, “Low-Rise, High Hopes.” Saffron notes that while “the human scale is very welcome, . . . brick and history come at a price. It costs the authority an average of $190,000 to build a rowhouse, roughly the same as private construction.” The final phase of the project featured “17 renovated and six new rental homes,” developed at an average cost of $309,000 a home, which was largely paid for with a federal stimulus grant; “PHA Opens New Public Housing in Mill Creek.”

[24] “Carl R. Greene,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_R._Greene.

[25] “Jannie Blackwell Quits PHA Board “To Be Part of the Solution,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 March 2011.

[26] Pew Charitable Trusts, Philadelphia’s Poor: How Financial Well-Being Affects Everything from Health and Housing to Education and Employment (Philadelphia: Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018), key findings.

To note also: HUD Section 8 rental vouchers, which allow low-income individuals and families “to move anywhere in Philadelphia with a guaranteed subsidy limiting their rent payments to 30 percent of their income” have “diminishing value.” Landlord participation is voluntary. Slightly more than two-thirds of Philadelphia landlords have rejected these vouchers. In the city’s “hot” housing market, they charge higher rents and dispense with federal red tape; “With Market Hot, Landlords Slam the Door on Section 8 Tenants,” New York Times, 12 October 2018.