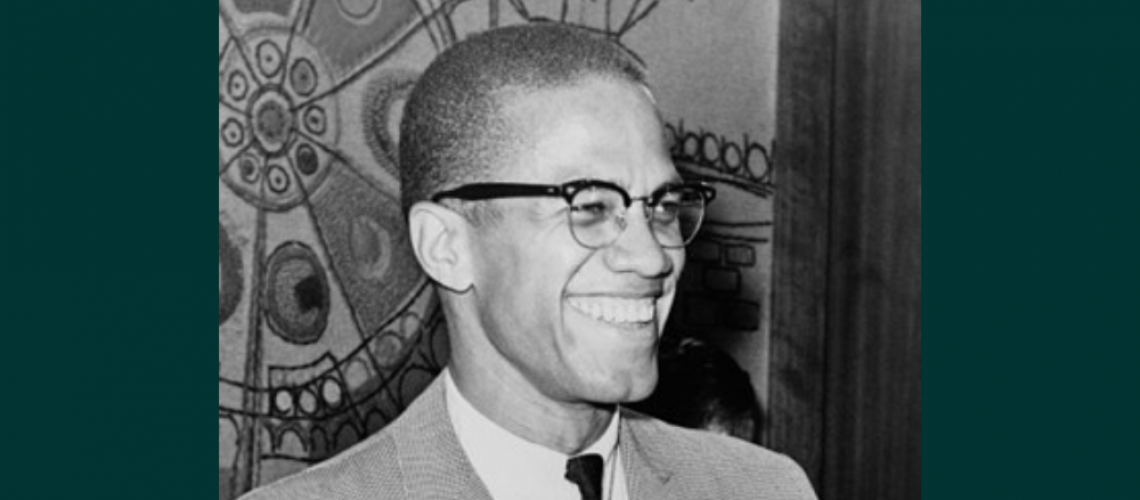

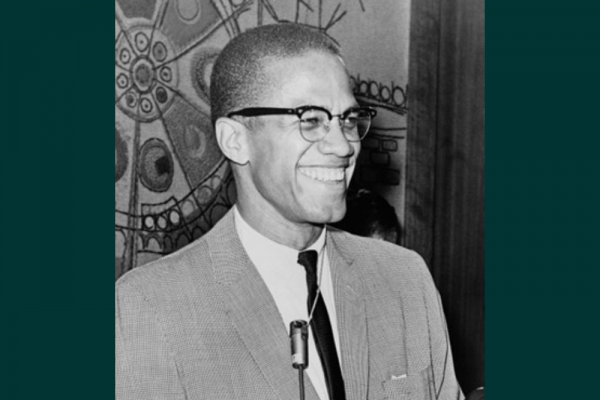

Malcolm X at the height of his international fame.

In the 1950s, Malcolm X was the national representative of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam (NOI). In the 1960s, he became a harsh critic of Elijah’s personal failures and NOI’s rigidly separatist and starkly apolitical theology. In the last years of his life, he converted to orthodox Islam and advocated for pan-Africanism. He is remembered in West Philadelphia as minister of Muhammad Temple of Islam #12.

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little to Louise and Rev. Earl Little in Omaha, NE, in 1925. In 1928, the family settled in Lansing, MI. Malcolm’s parents were followers of Marcus Garvey, with Earl serving as an organizer for Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the Midwest. In Lansing, two tragedies befell the Little Family—Earl’s violent death and Louise’s mental collapse—with dire consequences for young Malcolm, who became a juvenile delinquent, using his natural good looks, rhetorical gifts, and acute intellect for petty criminal escapades. In the early 1940s, Malcolm shuttled from one menial job to another in Boston, where he lived with his half-sister Ella, and in Harlem, New York City.

Malcolm X is the second iconic civil rights activist with an imprint on West Philadelphia. He belongs to a radical civil rights tradition that links him with Paul Robeson and Martin Luther King Jr. Part I looks at Malcolm X’s troubled childhood and youth as Malcolm Little.

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little in a hospital in Omaha, Nebraska on May 19, 1925. His parents were Grenada-born Louise Little (née Norton), a multilingual seamstress by trade, and Georgia-born Earl Little, a Baptist preacher and handyman. Before he married Louise in 1919, Earl had fathered and abandoned his first wife and their three children in Georgia. Malcolm was their fourth-born child. His parents were politically active followers of Marcus Garvey.

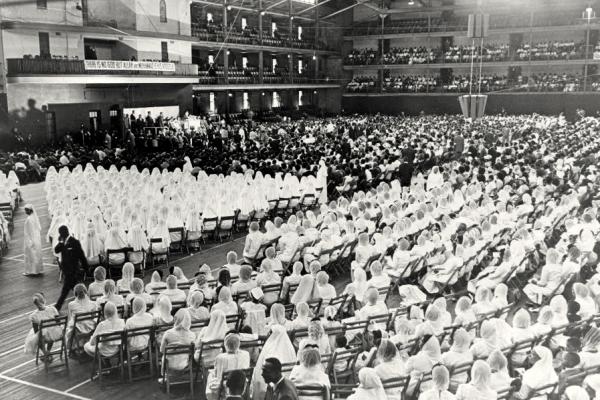

Jamaican expatriate Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) launched in Harlem in 1916. In the 1920s Garvey published the “Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World,” a call for displaced Africans and their descendants around the world to return to their homeland continent, where they would liberate sub-Saharan Africa from its European colonizers. Garvey’s campaign in the U.S. to unite “all people of African ancestry around the world into one great country” opposed the position taken by the NAACP, which regarded the U.S. as Black Americans’ hard-earned homeland. To the NAACP, Black Americans staked the moral high ground in their legislative and judicial struggle for civil rights and sought unimpeded opportunity to participate equally with whites in all venues of power. In 1924, after a surveillance campaign waged against him by the Bureau of Investigation (established in 1908, later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation), Garvey was imprisoned and later deported to Jamaica on a $25 charge of mail fraud. Until his death in 1940, Garvey directed his followers from Jamaica.

Having been threatened by torch-bearing Ku Klux Klanspeople, the Littles left Omaha in 1928, traveling first to Milwaukee, then to Lansing, Michigan. They lost their first house to a fire, after which Earl purchased a six-acre plot just south of the city. Here the family had a big garden and raised chickens and rabbits while Earl attended to UNIA work. During the Great Depression, Earl acted as Garvey’s representative in the Midwest, and the preacher-organizer took young Malcolm with him to UNIA meetings in different people’s houses. At home and on the road, the precocious Malcolm was imbued with a strong sense of Black pride. In 1931, Earl Little was killed by a Lansing streetcar, a bizarre and gruesome mishap that the Lansing coroner ruled accidental—though Malcolm believed his father was murdered by a Ku Klux Klan-like hate group, the Black Legion.

Earl’s first wife, Dorothy Mason, and their three children remained in Georgia. After Earl’s death, Louise, overwhelmed by her own family responsibilities, entered a downward spiral of mental collapse that led to her institutionalization in 1939; her eight children scattered. Malcolm took to Lansing’s streets and drifted into criminal activity (selling reefers, for example). After his arrest and trial, Malcolm was designated a ward of the state in 1939 and assigned to a white family’s supervision in a boarding house/detention home in Mason, a community twelve miles north of Lansing. He was allowed to attend Mason’s junior high school as the only Black child in a student body of some 300 whites; he excelled academically and socially, proving with his characteristic charm and guile, poise, straight talk, and forceful actions, that he was a formidable personality, and he was elected class president. His extraordinary promise notwithstanding, Malcolm’s high aspiration to be a lawyer and “a professional man of respect,”, was destroyed by his English teacher and advisor (gatekeeper), who counseled him to lower his sights, that his dream, as a Negro (the counselor used another word), was simply unrealistic, that white society would only accept someone like him as a carpenter. In 1940, for the 15-year-old Malcolm, this collision of social worlds was a turning point in the road that would lead him one day to regard whites as “white devils.”

That summer Malcolm traveled to Boston to stay with Ella Little-Collins, his mid-twentyish half-sister from Earl’s previous marriage. Ella, a formidable personality who lived in Roxbury, had prosperous hustles in Boston’s underground economy to which Malcolm was no doubt privy. Boston’s Black nightlife dazzled Malcolm. In the fall he moved back to Mason and lived with one of Mason’s few Black families. Likely emboldened by his experience in Boston, he gravitated to Lansing’s west side, where he again took up street life and this time flouted conventional racial norms by openly dating white girls. He also dropped out of school. A court petition led to his removal to a stricter Black household.

Then in 1941 Ella had 16-year-old Malcolm’s state custody transferred to her care in Massachusetts, 800 miles distant. When World War II broke out, Ella was able to shift from the underground economy to legal investments in real estate. Though she was a strict disciplinarian with Malcolm in her Roxbury home, she was unable to shield him from the dangerous lures of that era’s street life. Malcolm finagled a job as a shoeshine boy at the Roseland State Ballroom. Influenced by his shady half brother, Earl Jr., and Ella’s criminally inclined former husband, Malcolm used it as a staging ground for various street hustles. The payouts sufficed, at least for several months, to match Malcolm’s sophisticated sartorial tastes, which, combined with his light complexion, red hair, and tallness (he would reach 6’3”), dazzled Roxbury’s teenage girls. But the Roseland gig was short-lived, and 16-year-old Malcolm found himself ensconced in onerous menial jobs and petty street hustles.

Malcolm’s luck changed when the well-connected Ella arranged a railroad job for him through an official in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Malcolm was working as a sandwich man on the New York, Hartford & New Haven Railroad’s Yankee Clipper from Boston to New York’s Grand Central Station when he discovered Harlem, whose effect on him was mesmerizing. This route and his sandwich truck—he was known on the line as Sandwich Red—became his steady employment, with overnight stays in New York, where he rented rooms in Harlem hostelries and explored the district’s neighborhoods with newfound friends. Though his lodestar was Harlem during the war years (he called it “Seventh Heaven”), Harlem Red continued his ties with his criminal buddies in Boston.

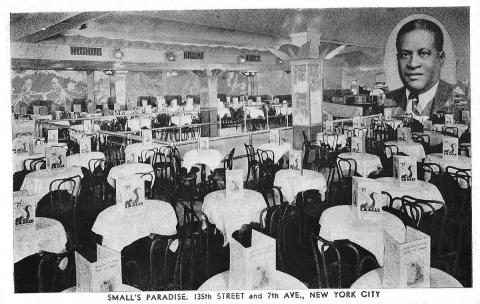

In the fall of 1942, when he had just turned 17, he lost his job with the railroad when his erratic behavior, fueled by alcohol and marijuana, outraged white passengers on the line. Wartime labor shortages allowed him to find another traveling job, this one as a sweeper on the Seaboard Line’s Silver Meteor, from New York to Florida. When he was again fired for misbehavior with passengers, Malcolm returned to Harlem and found work at Small’s Paradise, a popular restaurant on Seventh Avenue, where he learned the nuances of the city’s numbers racket. Malcolm lived in an apartment on Nicholas Avenue where he associated with big-time thieves and prostitutes. Years later, following his religious conversion, he would blame their underground activities on the blatantly racist social system which was engineered to deny Blacks the economic opportunities taken for granted by the controlling race. When Malcolm put Small’s Paradise in jeopardy by introducing a serviceman to one of his prostitute friends (though he was never a pimp), the establishment fired him. It was fall 1943. Malcolm, now 18-years-old and draft-eligible, was on the streets peddling reefers and working a night job at a speakeasy where he was called Detroit Red—a moniker that distinguished him from Chicago Red, a dishwasher and aspiring comedian at the same establishment whose real name was John Sanford, later the famous Redd Foxx of the 1970s sitcom Sanford and Son.

A Note on Sources: Indispensable sources for the WPCH articles on Malcolm X are two Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies—Les Payne & Tamara Payne, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X (New York, 2020); Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York, 2011). These biographies provide additions and corrections to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as Told to Alex Haley (New York, multiple editions from 1966). The most recent authoritative source, also indispensable, is Peniel E. Joseph, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. (New York, 2021), a comparative biography.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |