Drexel and Community Conflict in Unit 5

Drexel unveiled a plan in 1964 for expanding its holdings and building dormitories in Powelton Village and the planned projects were protested by community members until the mid-1970s.

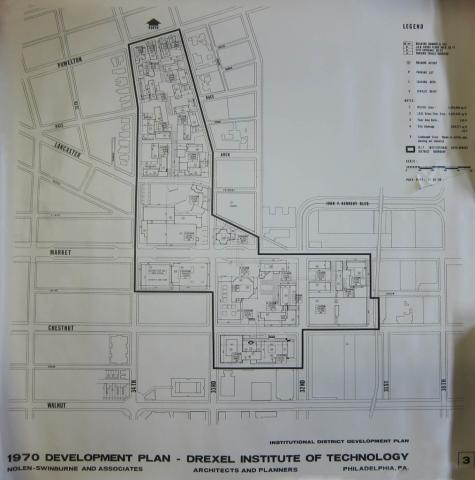

The Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority created Unit 5 of the University Redevelopment Area in 1961, with Drexel as the designated redeveloper. Drexel commissioned the firm of Nolen & Swinburne to design a master plan (called the 1970 Plan, it was completed in 1964), which projected Drexel’s campus expansion into Powelton Village. As construction of the 1970 Plan’s first building, Kelly Hall, Drexel’s first men’s dormitory, proceeded in 1965, the Institute and the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority were at loggerheads with the Powelton Civic Homeowners Association. Other community battles over dormitory placements would follow in the coming decade and disrupt Drexel’s timetable for campus expansion. After the 1970s, community protests abated as Drexel, now a university, slowed its expansion in the face of a mounting financial crisis.

In 1961, Philadelphia’s Redevelopment Authority (RDA) designated Drexel as the redeveloper for Unit 5. This was a continuation of the expansion created during a prosperous era under James Creese, Drexel’s president from 1945–1963.

Creese “is credited with restoring the Institute’s financial stability, boosting enrollments, doubling the size of the physical plant, and garnering federal Cold War dollars for Drexel’s programs.” During World War II, Drexel’s fortunes had declined precipitously. Tuition-dependent Drexel lost about half its students during the conflict, its enrollments declining from 5,000 to 2,600. Benefiting from an infusion of returning veterans, the Institute experienced a postwar resurgence.[1]

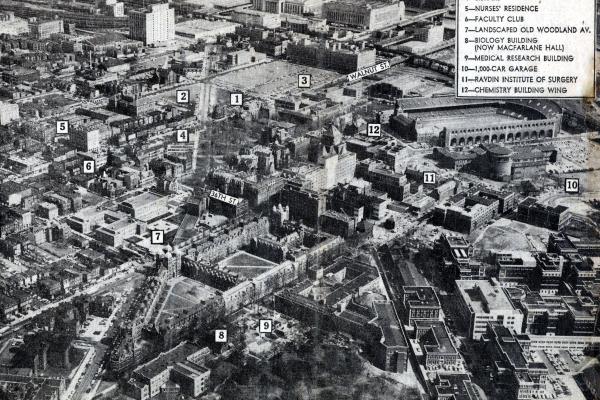

In 1955, Drexel completed Stratton Hall (basic sciences) on the corner of 32nd and Chestnut Streets. It was the Institute’s first expansion. In 1959, it built a new library (now the Korman Center) behind Stratton Hall.[2] Creese’s successor, William W. Hagerty (1963–1984) led Drexel’s advance further west and north of the central campus. Writes Miriam N. Kotzin, “Drexel’s campus grew from ten to nearly forty acres. Student enrollment doubled to 14,000 and the budget grew from 8 to 80 million…20 buildings were either built or acquired for [the] campus.”[3]

For the Unit 5 expansions, Drexel commissioned the firm of Nolen & Swinburne to design a master plan in 1964. The result was the “1970 Plan,” which projected Drexel’s campus expansion “west of Thirty-Third Street and north of Lancaster Avenue into Powelton Village.” At that time, Powelton Village’s boundaries included the blocks between 34th and 38th Streets from Lancaster Avenue to Spring Garden Street. As construction of the 1970 Plan’s first building, Kelly Hall, Drexel’s first men’s dormitory, proceeded in 1965, the Institute and the RDA were at loggerheads with the Powelton Civic Homeowners Association.[4]

Drexel’s plan to demolish, rather than conserve, existing buildings, and to erect new dormitories in their place spurred vigorous opposition in the local community. The Powelton Civic Homeowners Association (PCHA) demanded that the RDA limit Drexel’s expansion to six acres in the rectangle of Lancaster and Powelton Avenues and 33rd and 34th Streets, and oversee housing conservation in the rest of Unit 5. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, community action groups such as the PCHA and the East Powelton Concerned Residents (est. 1969), organized protests in the form of sit-ins, fence-busting forays, legal actions, and bulldozer blockages. At the center of the storm was the construction site for a new women’s dormitory, Calhoun Hall, which after a spate of lawsuits, arrests, and “physical confrontations,” managed to open at 33rd and Arch streets.[5]

After the 1970s, community protests abated as Drexel, now a university, slowed its expansion in the face of a mounting financial crisis: “Drexel built nothing beyond the central campus between 1977 (Meyers Hall) and 1986 (Towers Dormitory), and then not again until 1999 (North Residence Hall)—long decades of quiescence compared to the robust ‘urban renewal’ era of construction (and neighborhood tension) from 1963 to 1972.”[6]

The absence of protests, however, did not signal a reconciliation between Drexel and Powelton Village. Boorish student behavior was a perennial problem. “The placement of the fraternities, and ultimately the dormitories, along the north end of campus placed them between the university and Powelton Village and was a source of ongoing friction with the local residents,” writes David A. Paul in his published dissertation study. In addition to noise and drunkenness, some of the miscreant behavior was overtly racist in nature.[7] Drexel’s neighbor Penn had similar problems with fraternity bad boys in the 1980s and early 1990s.[8]