Migration and Immigration

Two large migration streams fed West Philadelphia’s population growth in the first half the 20th century: The “Great Migration” of southern blacks to northern cities, and a wave of “new immigrants” from eastern and southern Europe.

The first half of the 20th century witnessed dramatic shifts in the population composition of West Philadelphia. These changes were the result of two large migration streams. One stream was the “Great Migration,” which brought large numbers of African-Americans from southern states into northern cities. By 1960, African Americans were the majority race in West Philadelphia. The other migration stream consisted largely of “new immigrants” arriving from eastern and southern Europe prior to 1920, largely Russian-born Jews and Italians.

In 1900, 83% of the population of West Philadelphia consisted of whites who were born in the U.S. Over the next 40 years, there were dramatic shifts in the population composition. These changes were the result of two large migration streams. One stream was the “Great Migration,” which brought large numbers of African-Americans from southern states into northern cities. During the period 1900 to 1940, the black population of West Philadelphia rose from 5% of the total to 18%.

The other stream was European immigrants. When the 20th century started, the overwhelming majority of West Philadelphia’s foreign-born population was drawn from northwestern Europe, especially Ireland, Germany, and England. While the proportion of foreign-born in West Philadelphia would remain relatively stable at 20–25%, there would be a significant change in the countries of origin of the foreign-born population. This shift was skewed toward immigrants from eastern and southern Europe.

The Great Migration

A combination of push and pull factors spurred the Great Migration. Push factors were the injustices and deprivations imposed on southern blacks by Jim Crow laws and customs. The hardships meted out by Jim Crow differed in kind depending on the region, but not in degree. While some regions were less prone to antiblack violence than others, subordination of African Americans was uniform across the South. A black sharecropper in Bolivar County, Miss.; a black teacher in Monroe, La.; a black fruit picker in Eustis, Fla.--all endured subordination, though Bolivar County and Eustis, Fla. were more violently anti-black.1

In 1900, 83% of the population of West Philadelphia consisted of whites who were born in the U.S. Over the next 40 years, there were dramatic shifts in the population composition. These changes were the result of two large migration streams. One was the “Great Migration,” which brought large numbers of African-Americans from southern states into northern cities. During the period 1900 to 1940, the black population of West Philadelphia increased from 5% of the total to 18%. Yet the prospect of good jobs and freedom from Jim Crow restrictions proved illusory:

The great migration that was spurred by World War I and continued into the 1920s contributed some 140,000 southern blacks to Philadelphia’s total population, fostering the growth of three sizable black districts: the southern tier of Center City, North and West Philadelphia (the old 24th Ward, Market Street to Girard Avenue, 32nd to 44th). Relegated to the bottom rung of the city’s economic ladder, with the exception of a small middle class of African American doctors, lawyers, teachers and caterers (“Old Philadelphians” like the attorneys Raymond Pace Alexander and his wife, the precocious Sadie Mossell Alexander), blacks encountered wretched housing conditions in a rent-profiteering market and entrenched hostility, denigration, harassment, and violence at the hands of Philadelphia’s Irish, Italian, and “old-stock” Euro-American groups. African American employment gains during World War I, primarily in the railroad and steel industries, dissipated after the war: “domestic service and unskilled labor” were the only jobs available for the large majority of Philadelphia blacks, many of whom were unemployed. In the city’s heavily segregated textile industry, blacks could only find jobs as janitors.2

By 1960, Cobb’s Creek, the area’s largest neighborhood, was large-majority African American.

Immigration

When the 20th century dawned, the overwhelming majority of West Philadelphia’s foreign-born population was drawn from northwestern Europe, especially Ireland, Germany, and England. While the proportion of foreign-born in West Philadelphia would remain relatively stable at 16-17% for the first three decades, there would be a significant change in the countries of origin of the foreign-born population. This shift was skewed toward immigrants arriving from eastern and southern Europe.

Not all of these “new immigrants” who arrived at the Port of Philadelphia settled in Philadelphia. For example, immigrants from Poland once landed tended to bypass Philadelphia, moving in large numbers to other cities. Only 10% of Polish immigrants in the U.S. settled in Philadelphia. Two groups that did choose Philadelphia in large numbers were eastern European Jews, born in what was then part of Russia, and Italians. From 1900 to 1920, the Jewish population in West Philadelphia increased from 241 to about 12,000, and in 1930 the number was over 18,000. Most of this increase probably occurred before 1924, when Congress limited immigration from Eastern Europe.

Among the “old immigrant groups,” the Irish continued to be an important source of immigration to West Philadelphia. Collectively, immigrant groups played an important role in the development of West Philadelphia in the decades before World War II. Their impact was especially important to the development of several neighborhoods north of Market St. and west of S. 40th St.

What U.S. Census Maps and Graphs Tell Us

Here we provide an interpretation for each numbered image (map or graph) in the Related Media column of this story.

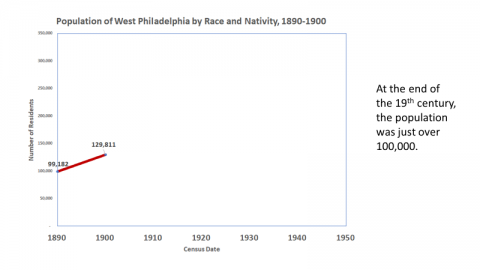

#1. Population of West Philadelphia by Race & Nativity, 1890-1900

At the end of the 19th century, the population of West Philadelphia was just over 100,000.

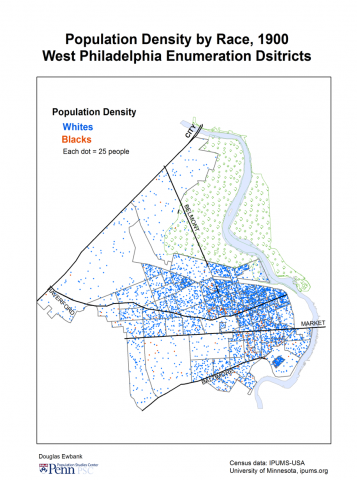

#2. Population Density by Race, 1900, West Philadelphia Enumeration Districts

At the turn of the last century, the population was heavily concentrated at the east end of West Philadelphia, near the bridges to Center City. At the west end, many large estates and farms were to be found. Whites were overwhelmingly the dominant racial group, concentrated in West Philadelphia’s streetcar suburbs. Much of the area shown at the center of the map below Market St. was what the urban historian Kenneth Jackson calls a “crabgrass frontier”; its development awaited the coming of the Market St. Elevated.

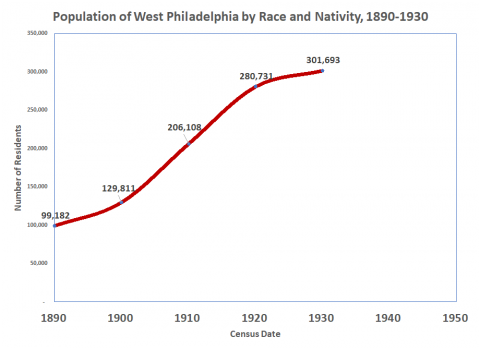

#3. Population of West Phialdelphia by Race and Nativity, 1890-1930

Between 1900 and 1920, West Philadelphia’s population more than doubled. In 1930, it leveled off at three times the population in 1890.

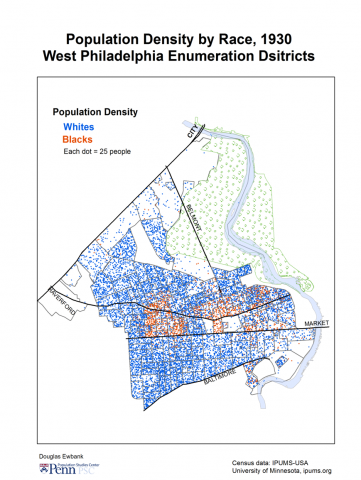

#4. Population Density by Race, 1930, West Philadelphia Enumeration Districts

By 1930, West Philadelphia’s population had increased to fill in the southern and most of the western areas. The black population consisted of 14.4 percent of the total. The largest numbers lived in Haddington (34%), Mill Creek (19%), and Mantua (12%).

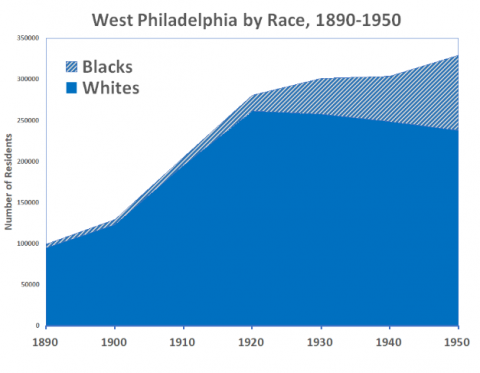

#5. West Philadelphia by Race, 1890-1950

This graph shows the steady growth of the black population in West Philadelphia between 1920 and 1950, paralleling a gradual but steady decline of the white population. In 1950, despite their reduction, whites remained the large-majority racial group, totaling 71.9% vs. 27.9% for blacks, and .2% for “other." (Calculations from 1950 U.S. Census reported in westphillyhistory.archives.upenn.edu/statistics/census.)

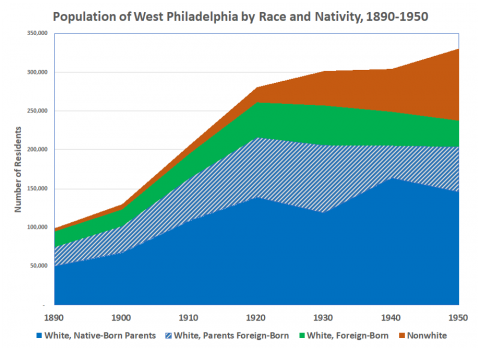

#6. Population of West Philadelphia by Race and Nativity, 1890-1950

During this 60-year period, West Philadelphia’s population more than tripled—an average growth rate of 3.8% per year. Note that in 1920, the foreign-born and the children of immigrants comprised almost half of West Philadelphia’s population. This graph also depicts the steady growth of the area’s black population between 1920 and 1950.

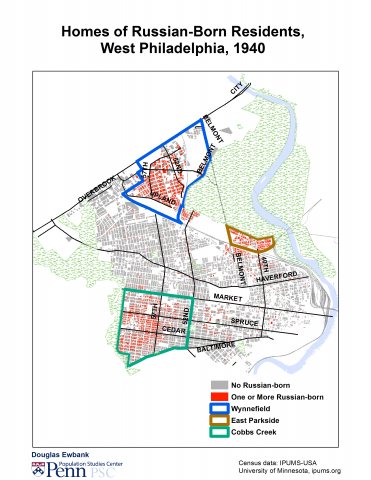

#7. Homes of Russian-Born Residents, West Philadelphia, 1940

Russians were one of the largest immigrant groups in West Philadelphia in 1940. They accounted for about 7% of adults. We know from the 1930 Census that almost all individuals in West Philadelphia who were born in Russia were Jews who spoke Yiddish. Not all Jews in West Philadelphia were born in Russia. For example, 64% of immigrants from Poland reported speaking Yiddish.

The Jewish population of West Philadelphia increased rapidly after the turn of the century. In 1900, there were only 241 Immigrants from Russia. By 1920, this had increased to about 12,000, and in 1930 it was over 18,000. Most of this increase probably occurred before 1924, when Congress limited immigration from Eastern Europe. Despite the concentration of Jews in parts of West Philadelphia, more than three quarters of Yiddish-speakers in Philadelphia lived in other parts of the city.

The largest concentration of Yiddish-speakers in West Philadelphia was in Cobbs Creek—about 6,500 in 1930. The other prominent concentrations were in Wynnefield and Wynnefield Heights (4,750), and East Parkside and northern Belmont (3,936).

Note A: The 1930 census asked the main language spoken by all foreign-born individuals. This was important for identifying ethnic groups because of the large number of border changes after World War I. The 1940 census only asked this question of a sample of about 6% individuals. The data from the 1940 sample on the language spoken by Russian-born individuals is consistent with the 1930 data.

Note B: The base maps for the current properties are from the City of Philadelphia. J. M. Duffin mapped the properties absorbed by the University City Science Center. The other historic properties were mapped by Douglas Ewbank.

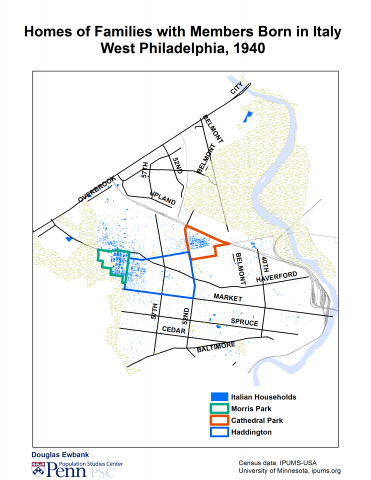

#8. Homes of Families with Members Born in Italy, West Philadelphia, 1940

In 1940, 6,600 Italians immigrants lived in West Philadelphia, second only to Russian-born Jews in the immigrant population. They settled in two areas. Half lived in Morris Park and the neighboring areas of Haddington west of 60th St. and southern Overbrook west of Wynnewood Rd. One-fourth of adults in this area were born in Italy; 40% were either born in Italy or had a parent born there.

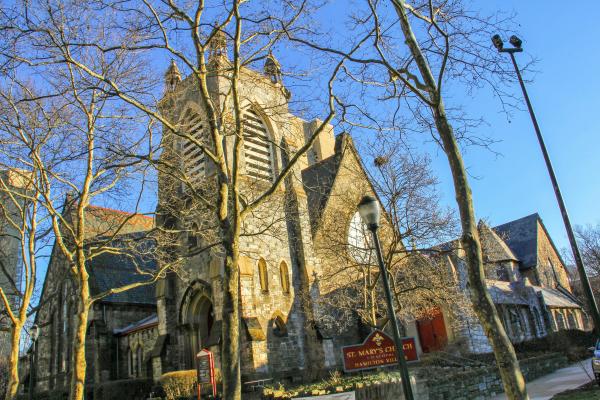

The other area was in Cathedral Park which was the home to another one-fifth of West Philadelphia’s Italians. That neighborhood was split into two sections on opposite sides of Cathedral Cemetery. South of the cemetery was predominately Irish. North of the cemetery was predominately Italian. Between the cemetery and Lancaster Ave., 23% of adults were born in Italy—37% were either born there or had a parent who was.

Note A. The base maps for the current properties are from the City of Philadelphia. J. M. Duffin mapped the properties absorbed by the University City Science Center. The other historic properties were mapped by Douglas Ewbank.

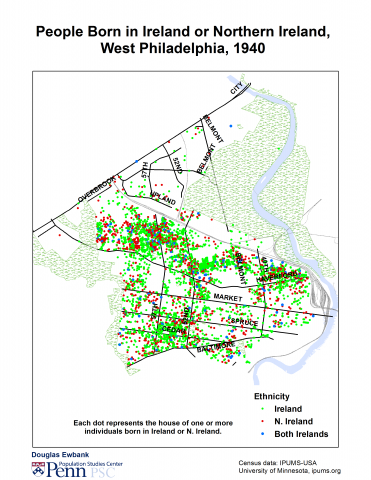

#9. People Born in Ireland or Northern Ireland, West Philadelphia, 1940

In 1940, households with one or more members born in either the Irish Republic or Northern Ireland were dispersed throughout West Philadelphia. A relative handful of households represented “both Irelands,” where at least one person in the dwelling unit (a house or apartment) was born in the Republic and one in Northern Ireland.

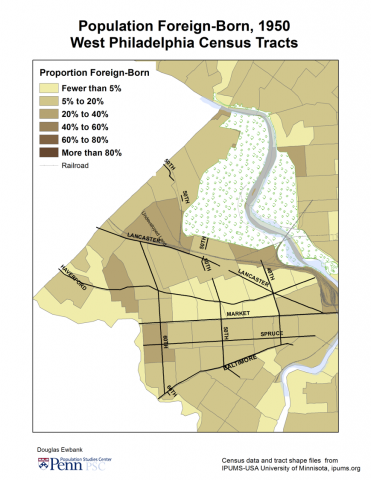

#10. Population, Foreign-Born, 1950, West Philadelphia Census Tracts

In 1950, West Philadelphia’s population still included 10% who were immigrants and many whose parents were foreign-born. In some neighborhoods, more than 20% were born abroad.

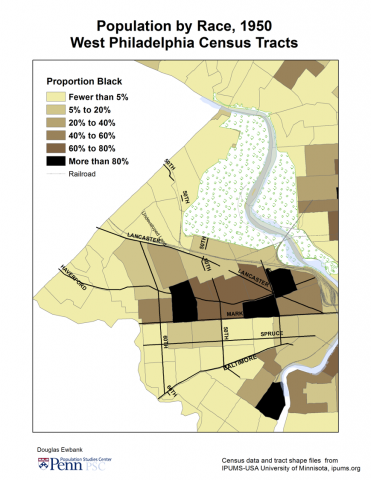

#11.

In 1950, the black population of West Philadelphia remained concentrated north of Market St., with some areas more than 80% black. (This map also shows an African American neighborhood in Southwest Philadelphia.)

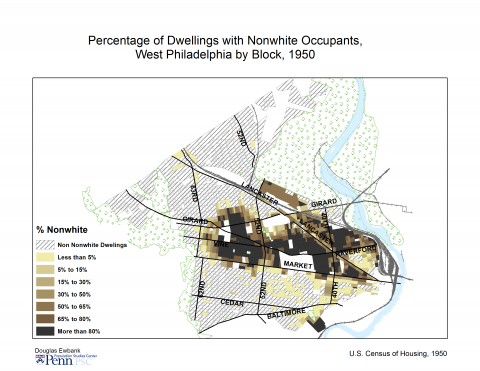

#12. Percentage of Dwellings with Nonwhite Occupants, West Philadelphia by Block, 1950

Nonwhite housing occupancy is another indicator of the concentration of West Philadelphia’s black population north of Market St. in 1950.

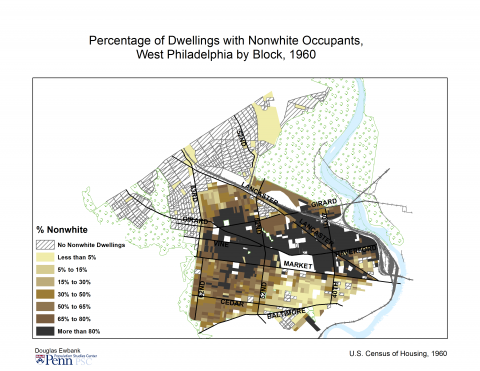

#13. Percentage of Dwellings with Nonwhite Occupants, West Philadelphia by Block, 1960

West Philadelphia’s population shifted from majority-white to majority-black between 1950 and 1960. In 1960, the black and white shares were 52.4% and 47.2%, respectively. West Philadelphia’s total population was 301,830, with blacks numbering 158,176; whites, 142,368. (U.S. Census compilations for 1950 and 1960 in westphillyhistory.archives.upenn.edu/statistics/census.)

The decade was one of overall population decline. While the black population increased by 72%, the white population declined by 40%. The “nonwhite” population was 99.2 percent black.

This map indicates surging black growth south of Market St., in the Cobb’s Creek neighborhood, which accounted for much of this shift.

[1] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration(New York: Vintage, 2010).

[2] John L. Puckett and Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950-2000(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2015). The authors draw from James Wolfinger, Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 11-35.