Bridging the Schuylkill: Early- to Mid-19th Century

Bridges built at strategic ferry crossings spanned the Schuylkill in the early- to mid-19th century, making West Philadelphia a thriving conduit for trade between the city and its western hinterland area and spurring the economic and residential development of Blockley Township.

Improvements in transportation in the first half of the 19th century included the replacement of ferries with horse-carriage and railway bridges that crossed the Schuylkill. These bridges facilitated a more efficient flow of agricultural and artisan goods between the city and its western hinterland area. The signficance for Blockley Township was economic and residential growth.

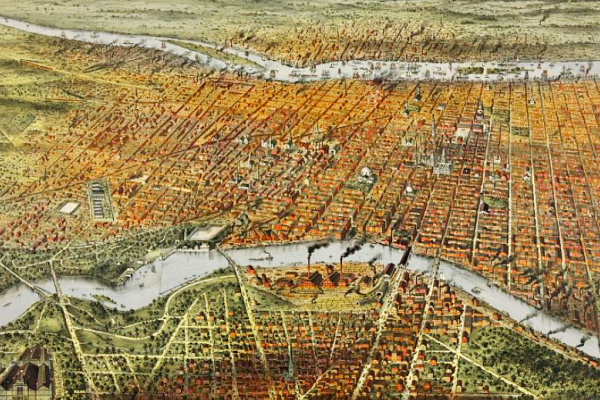

In the nineteenth century, West Philadelphia transformed from a countryside of family farms and "gentlemen’s" estates to a collection of residential communities. The building of bridges across the Schuylkill River promoted development. Traffic of goods and people between Philadelphia and the city’s hinterland west of the Schuylkill had greatly increased over the course of the 18th century with the growth of agricultural production, but until the first decade of the nineteenth century, traffic across the river was chiefly handled by three ferries: "Gray’s Ferry" on the south; the "Middle Ferry" at present-day Market Street; and the "Upper Ferry" at present-day Spring Garden Street. But even before a more efficient means of bridging the river came of issue, the greater settlement of Philadelphia’s western hinterland area rested on the building and improvement of road and wagon ways.1

As early as 1683, work had begun on what was variously called "Blockley and Merion Turnpike" or "Plank Road," a route used by Welsh Friends of Merion to go from their meeting house to the Upper Ferry on the Schuylkill. Part of this road evolved into present-day 54th Street and Lancaster Avenue.2 In 1722, a committee was appointed to plan further road connections from points in Blockley Township to the river.3 In 1786, a large project was initiated to construct the "First Long Turnpike in the United States."4 This "first important public improvement in the state" was completed by the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road Company. The turnpike was completed for public use in 1795 and extended from Philadelphia to Lancaster.5

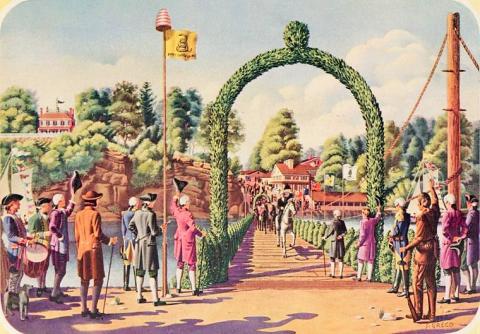

Improvement of roads and increased wagon traffic did not force innovations in bridging the Schuylkill River. War did. In 1776 at the outset of the American Revolution, George Washington, military leader of the colonial uprising, ordered the erection of a bridge connecting Philadelphia to the west and General Israel Putnam supervised its construction. This bridge, jury-rigged at the Middle (High St.) Ferry, was a primitive construction involving floating logs and scows (a type of flat-bottomed boat); with the later British occupation of Philadelphia, the bridge was destroyed and the scows were hidden in the marshes.6 The British oversaw a second bridge project at Gray’s Ferry. In 1777, Lord William Howe deputed Captain John Montressor to construct a bridge across the Schuylkill. However, the bridge was hastily built and was destroyed by the rushing water shortly after its completion. Montressor and a team of engineers then gathered the debris and built a third bridge in the same location. The Gray’s Ferry bridge remained after the British evacuated the area. The English traveler Henry Wansey described the bridge as:

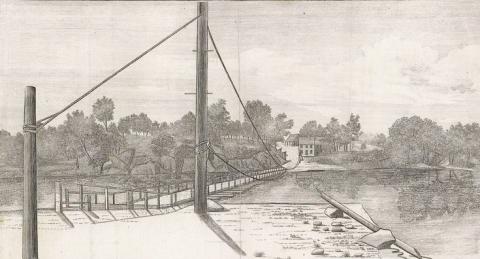

[two iron chains] strained across the river parallel to each other, about six feet distance; on it are placed flat planks, fastened to each chain; and in this the horses and carriages pass over. As the horses stepped on the boards they sank under the pressure and the water rose between them; no railing on either side, it really looked very frightful and dangerous.7

See more below on Gray’s Ferry

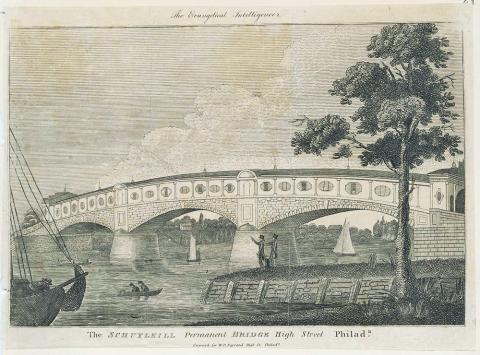

In the 1780s, Thomas Paine, the famed author of the revolutionary tract Common Sense and a leading figure in the American Revolution, rendered plans for the construction of an iron bridge across the Schuylkill. However, the project lay idle and in 1798 a design by Timothy Palmer for a wooden bridge was selected over Paine’s model. On 18 October 1800, construction began on Palmer’s Permanent Bridge at Market Street. The Permanent Bridge opened to the public in 1805. The covered bridge spanned the 550-foot length of the river with a series of arches and was 1300 feet long in total construction.8

The Permanent Bridge facilitated expanding traffic across the Schuylkill until 1850, when it was engulfed and destroyed by fire. The bridge was then reconstructed and widened to incorporate tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad (the mainline tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad and its successors connecting Philadelphia and Pittsburgh and points further west runs through a wide swathe of West Philadelphia to this very day).9 Fire would also destroy this bridge in 1875; a truly permanent Market Street Bridge constructed with iron spans and stone fortifications would open in 1887.10

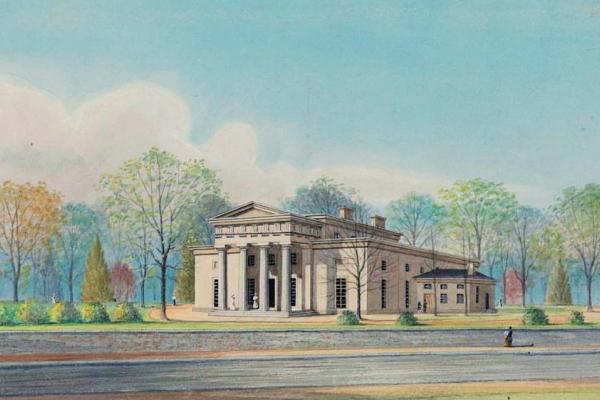

No sooner than the completion of the first standing bridge across Schuylkill in 1805, pressure mounted for another span—this time with residential community-building west of the Schuylkill in mind. In 1809, Judge Richard Peters, owner of the Belmont estate along the northwest banks of the Schuylkill in Blockley Township, announced a plan to subdivide his lands and build suburban homes.

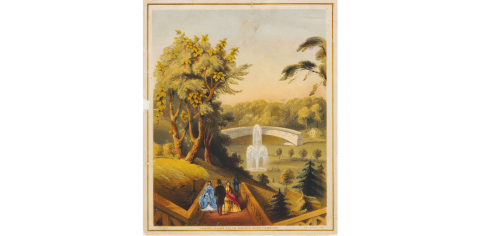

The neighborhood of Mantua would thus emerge.11 To allow eased access to the community from Philadelphia, petitions to the state legislature soon were filed for public construction of a bridge at Spring Garden/Fairmount (to replace private ferry service at that location). The German engineer, Lewis Wernwag, proposed a splendid design for the bridge. The state legislature then contracted with Wernwag’s company, and the wooden Wernwag Bridge, hailed as the “Colossus Bridge,” opened in 1812. The bridge was the longest single-span bridge in the world. It had a single arch that spanned 343 feet, ninety feet longer than any other bridge.

The Spring Garden Bridge spurred immediate real estate development in Mantua. Following Judge Peters’ lead, John Britton, Jr., a local developer, announced in April of 1813 his plan to sell lots in Mantua for suburban home building and Philadelphians quickly responded.12 By the time the doors of the newly constructed First Presbyterian Church of Mantua opened in 1846, Mantua was a budding neighborhood of streets and homes with little evidence of the estates that had marked the area a few decades before.13

The Wernwag Bridge burned in 1838 and was replaced by a wire suspension bridge built in 1842 by Charles Ellet. “This was the first successful wire suspension bridge in America.” The bridge conveyed pedestrians, horsecars, and horse-drawn carts. It was replaced in 1875 by an iron truss bridge named the Callowhill Street Bridge, built by the Keystone Bridge Co. A “double-decker bridge,” it carried streetcars and horse-drawn carts on the upper deck and trains (later removed) on the lower deck. With some improvements, this bridge would remain in use until 1964.14

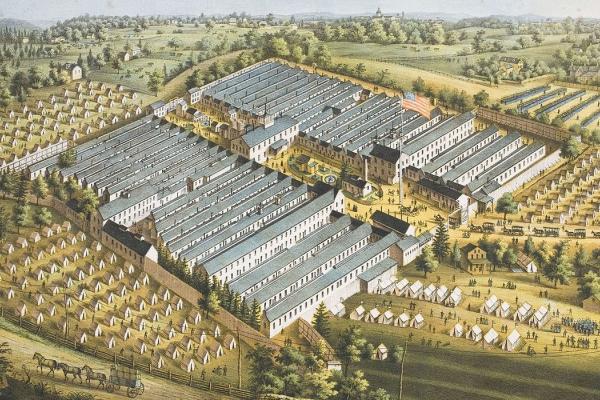

The fourth bridge of the National Period was a permanent bridge at Gray’s Ferry, where, until 1838, the Schuylkill was crossed by a series of unstable floating bridges. That year, the Newkirk Viaduct, a railroad bridge, opened at Gray’s Ferry, providing rail transport between Wilmington and Philadelphia; the new bridge was “a covered truss structure supported by five piers”; it featured a section that could be swiveled to allow passage of ship and boat traffic. As the century closed, a new bridge was needed to meet the demand for trolley service between the neighborhoods of Gray’s Ferry and Kingsessing and the central city.15

1. The “Middle Ferry” at High St. (today’s Market St.) was likely in operation by 1683. “Schuylkill ferries were rigged with ropes running from shore to shore, by means of which the boats were drawn across.” J. Thomas Scharf and Wescott Thompson, History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts, 1884), 2139–40.

2. Tello J. Apery, Overbrook Farms: Its Historical Background, Growth and Community(Philadelphia: Magee Press, 1936), 38, 49–50.

3. M. Lafitte Vieira, West Philadelphia Illustrated(Philadelphia: Avil Printing Co., 1903), 37.

6. Bennett Nolan, The Schuylkill(New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1951), 249–50. See also & cf. Scharf and Thompson’s 1884 account in History of Philadelphia.

8. John Lewis, The Reputation of the Lower Schuylkill(Philadelphia: Enterprise Publishing Co., 1924), 3.

9. Viera, West Philadelphia Illustrated, 36.

11. Leon Rosenthal, “Mantua: The Real Estate Promotion That Grew and Grew,” A History of Philadelphia’s University City(Philadelphia: Printing Office of the University of Pennsylvania, 1963), unpaginated.

13. Preston Thayer and Jed Porter, Workshop of the World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990), https://www.workshopoftheworld.com/west_phila/west_phila.html, accessed 20 Feb. 2008.