Permanent European Settlement and 18th-Century Estate Building

The 18th century saw the departure of the Lenape and the permanent European settlement of West Philadelphia, at the time called Blockley Township. Large estates were a characteristic development that gave rise to the villages of Hamiltonville and Powelton.

The first settlers in William Penn’s proprietary colony typically built modest log and frame houses. By the end of the 18th century large estates—with two-story brick and stone houses—had been developed along the banks of the Schuylkill River. Of note were the mansions and estates of the Hamilton and Powel families, whose names were assigned to the small villages of Hamilton (or Hamiltonville) and Powelton.

With the departure of the Lenape, British farmers and craftsmen and later, Americans with substantial resources developed West Philadelphia. The first settlers typically built modest log and frame houses, but by the end of the 18th century large estates—with two-story brick and stone houses—had been developed along the banks of the Schuylkill River. William Warner (ca. 1627–1707), a native of the parish of Blockley in Worcestershire, England, led the way.1

William Warner

William Warner is an important figure in the history of West Philadelphia. Warner arrived in the Delaware Valley in the mid-1670s and by 1677 had settled on the west bank of the Schuylkill River. It is said that he negotiated with the Lenape and purchased rights from them to 1,500 acres of land. In any case, in the spring of 1678 he obtained from the Upland Court (located at present-day Chester, Pennsylvania) a formal order confirming his rights to 100 acres of land in West Philadelphia. Two years later he obtained from the same court legal recognition of his rights to a contiguous tract of 200 acres, and in 1681, still another 400 acres. When William Penn took control of Pennsylvania, Warner (and his family) patented a total of 588 acres with the new government. Warner’s will, 1703, divided his Schuylkill estate among four heirs.2

The original farm of 300 acres fronted on the Schuylkill River in present-day Fairmount Park (at the site of Samuel Breck’s 1797 mansion house, "Sweetbriar") and stretched west, between narrow boundaries, as far as 60th and Media Streets. Warner named his farm "Blockley," after his birthplace in England.

Warner was also a community leader in the first years of William Penn’s new colony. He sought election to public office and was rewarded with two terms in the Pennsylvania Assembly, the first in 1683 and the second in 1691. He was also a justice of the peace for Philadelphia County in 1685 and 1686.3 His influence proved lasting, for in 1705, when the entire 14.2 square mile area we know of as West Philadelphia today was first organized as a political entity, it was officially named Blockley Township.

The Blockley name identified West Philadelphia for nearly 150 years. Not until 1854, when the City of Philadelphia expanded and incorporated all the townships in Philadelphia County, did a ward number substitute for Blockley as the designation for West Philadelphia.

John Bartram and his Family

Two miles south and west of the Warner settlement—but also on the west bank of the Schuylkill River—another prominent early Pennsylvanian, John Bartram (1699-1777), made his home. John Bartram is generally recognized as the father of American botany and the first North American to hybridize flowering plants.4

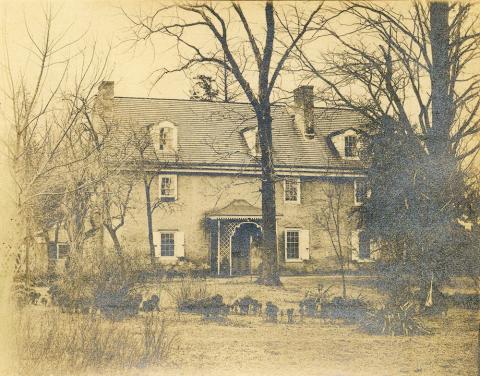

Bartram was born on a farm just west of Philadelphia, in Chester County, Pennsylvania. In 1728 he purchased a farm of 102 acres on the west bank of the Schuylkill and soon thereafter constructed a two-story stone house for himself and his family. He prospered. The origins of Bartram’s interest in flowers are unknown—he perhaps was fascinated by the medicinal powers of plants. In 1736 he traveled upstream on the Schuylkill collecting plants for exchange with Peter Collinson, his British correspondent. Two years later he undertook the first of his North American explorations, traveling more than 1,000 miles up the James River in Virginia to study the natural history of that region.

Bartram discovered several native floras, of which the Franklinia alatamahatree is his most famous. John Bartram’s fame grew throughout the American colonies and in Europe (Bartram maintained correspondence with European botanists and regularly sent them clippings of plants and seeds—all rhododendrons in Europe, for example, date back to Bartram’s shipments). In total, it is believed that Bartram helped to identify, cultivate and preserve more than 200 American plant species.5

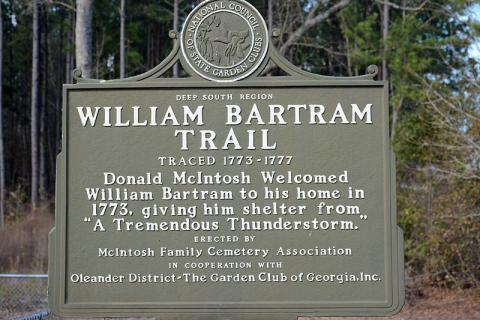

John Bartram’s son, William Bartram (1739-1823), would come into his own as a famous and respected botanist for the documentation of his travels. In 1773, William Bartram began a tour of the southern colonies that lasted four years and he recorded his experience; a published version of his journals with his drawings drew acclaim as an "American natural history classic."

Another of John Bartram’s sons, John Bartram Jr., turned his father’s gardens into a commercial venture. He published one of the first catalogs for the mail-order sale of plants and seeds.6 Such famous American founding fathers as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson purchased flowers and seeds from the Bartrams for their gardens, adding to the renown of John Bartram and his sons.

Today, one can tour Bartram’s Gardens and see various plants Bartram helped to cultivate as well as his home, which serves as a museum. The Garden now occupies forty-five acres, much smaller than the original 102-acre site. The preservation of the Bartrams’ contributions to botany is due to the philanthropy of Andrew Eastwick, a successful railroad executive, who purchased the estate and ceded the grounds to the city of Philadelphia in 1891 for public use. Those interested in the history of West Philadelphia may visit Bartram’s Garden from its entry at 54th Street and Lindbergh Boulevard in southwest Philadelphia.

William Hamilton and the Woodlands

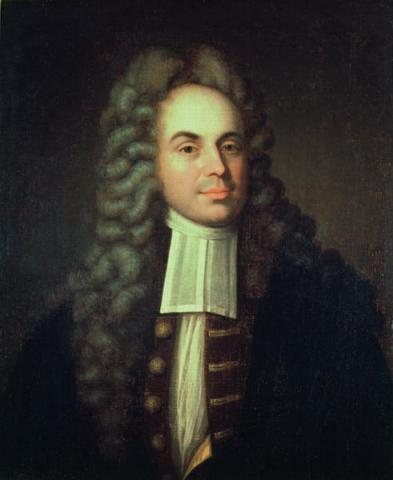

Nearly a century after William Warner, another man, William Hamilton (1745-1813) came to exemplify estate building along the western banks of the Schuylkill River. He was the grandson of the famous Philadelphia lawyer, Andrew Hamilton (ca. 1676–1741), a major legal and political figure in Philadelphia in the first half of the 18th century. Andrew Hamilton, whose British origins are obscure, arrived in Virginia in 1700 and rapidly became a prominent attorney in both Virginia and Maryland.7 He moved to Philadelphia in 1715 and just two years later was named Attorney General of the Province of Pennsylvania. He was also a major investor in Pennsylvania land, including 300 acres on the west bank of the Schuylkill River in Blockley Township, which he purchased in 1735.

In that same year Andrew Hamilton became the most famous lawyer in colonial America when he successfully defended John Peter Zenger, publisher of the New York Weekly Journal, in a landmark free-speech case. New York authorities had accused Zenger of "seditious libels." Andrew Hamilton won an acquittal for Zenger by challenging the law rather than proving his client’s innocence.The case ultimately contributed to the adoption of the principles of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Hamilton’s abilities in litigation at the trial gave rise to the expression "Philadelphia lawyer."

At his death, in 1741, Andrew Hamilton willed his West Philadelphia land to his son, Andrew Jr. The younger Andrew lived only until 1747, when he willed "his Plantation on the West side of the Schuylkill, containing about 356 acres," to his son, William. Nearly thirty years later, in 1776, another son of the elder Andrew Hamilton, James (ca. 1710-1783), purchased an additional 179 acres in West Philadelphia, a tract of land that was contiguous with William Hamilton’s estate. When James Hamilton died in 1783, he bequeathed all 179 acres to William. In this manner—356 acres from his father, Andrew the second, and 179 acres from his uncle, James—William Hamilton, by 1785, came into ownership of approximately 535 acres of West Philadelphia land. William Hamilton’s estate stretched from the Schuylkill River on the east to present-day 43rd Street on the west, and from present-day Market Street on the north to the present-day Woodlands Cemetery on the south.

By 1785, other wealthy Philadelphians were purchasing open land and building grand mansion houses along both the east and west banks of the Schuylkill River. Many of these "country estates" were later purchased by the City of Philadelphia and consolidated within the present-day boundaries of Fairmount Park. On the east side of the river were, for example, John Macpherson’s "Mount Pleasant" (1765) and the Rawle family’s "Laurel Hill" (1767). On the west side were William Peters’ "Belmont" (1744) and on the old Warner farm, the imposing club house of the gentlemen members of the "Schuylkill Fishing Company" (ca. 1747, but now demolished). William Hamilton decided to follow their lead.

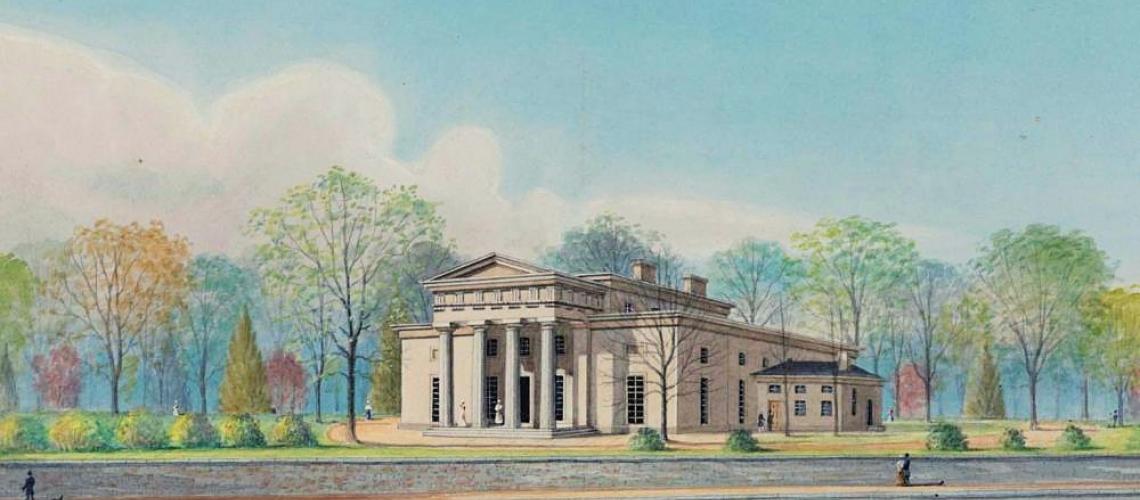

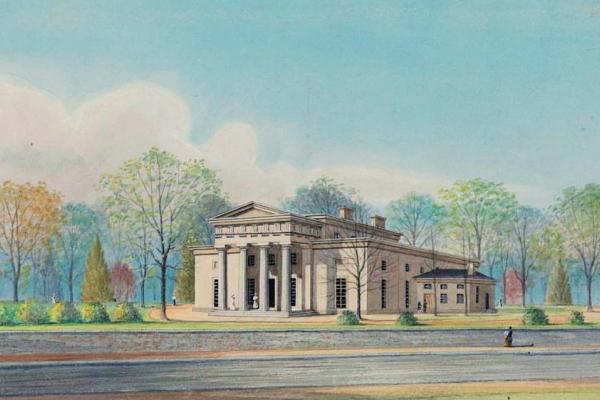

In 1788, near the southwest corner of his inherited estate, William Hamilton built a fashionable, two-story, stone mansion house which featured oval rooms and sweeping views of the Schuylkill River and southwest Philadelphia. He decorated the house with fancy English furniture and fine art. Perhaps most notably, he developed extensive gardens and filled them with native and exotic plants from across America and around the world. In 1798, at the time of that year’s U.S. Direct Tax, the tax assessors described an estate which included not only the 7,100 square foot main house, but also a hot house, greenhouse, seed house, tea house, ice house, coach house and stable, and two porter houses. William Hamilton called his place the "Woodlands" and for a quarter century—until his death in 1813—travelers throughout the English-speaking world came to see it.

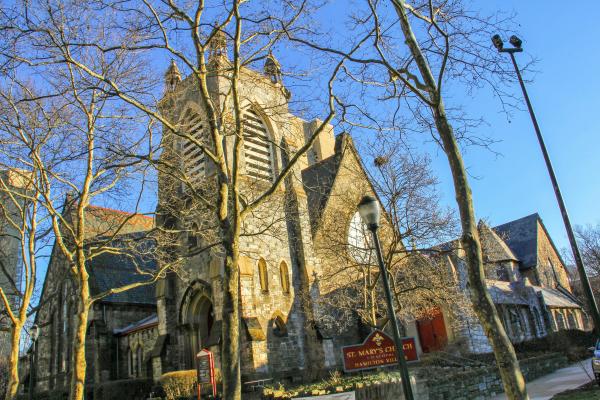

Over several years and in several transactions Hamilton’s heirs sold the Woodlands, but the mansion house itself has survived to the present day as the office and administration building of the Woodlands Cemetery, formed from part of the estate in 1840. Those interested in the history of West Philadelphia may visit the Woodlands through a magnificent gate to the cemetery grounds at 4000 Woodland Avenue.

More Mansions and Estates West of the Schuylkill

North of the Woodlands, that is, north of present-day Market Street, there were, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a series of grand mansion houses and country estates on the west bank of the Schuylkill.

The first of these was the Powel family’s 97-acre "Powelton," followed to the north by:

- A ninety-five-acre property owned by Anne Willing Bingham;

- John Britton’s ferry house and ferry, known as the "Upper Ferry on Schuylkill," which included fifty-eight acres of land (in 1798 Britton sold the ferry house, ferry, and fourteen acres to Adam Siter);

- David Beveridge’s property of twenty-nine acres;

- Judge Richard Peters’ estate "Mantua Farm," which extended to 227½ acres.

By the late 19th century, however, all five of these houses had been demolished and their grounds developed into the present-day neighborhoods of Powelton Village and Mantua. In addition, the land directly on the Schuylkill was taken up by the Pennsylvania Railroad for its rail lines and freight depot.

Still more fancy houses and gardens lined the Schuylkill farther north. Just beyond the Pennsylvania Railroad’s freight yard were:

- John Penn’s "Solitude" (the house still stands on the grounds of the present-day Philadelphia Zoo);

- The Warner family’s "Egglesfield”;

- Samuel Breck’s "Sweetbriar”;

- William Bingham’s showplace, "Lansdowne”;

- The Peters family’s "Belmont."

The last four of these estates were later incorporated into Philadelphia’s present-day Fairmount Park. The houses known as "Belmont" and "Sweetbriar" have survived to the present time and are open for tours at regular hours.

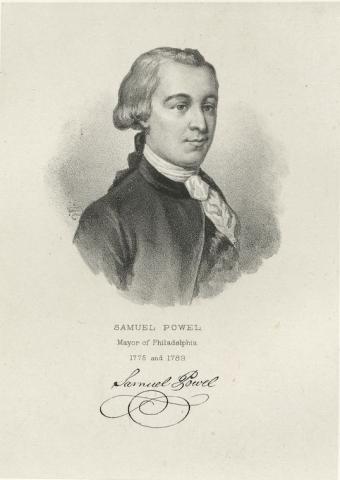

Powelton: A Tale of Three Families

The story of Powelton illustrates the eventual denser, residential development of West Philadelphia as well as any of these country estates. It was home to one of the greatest Greek Revival mansions in the entire Delaware Valley; its ninety-seven acres extended, in present-day terms, from the Schuylkill River on the east, 36th Street on the west, Lancaster Avenue on the southwest, and Powelton or Pearl Street on the north. Samuel Powel (1738–1793) and his wife, Elizabeth (“Eliza”) Willing Powel (1742–1830) purchased the land in 1775 and built a country house there called “Powelton” sometime before 1783.

Eliza Powel was a formidable woman of the late-18th century. She made her mark on the national stage during George Washington’s presidency (April 1789–March 1797), when Philadelphia was the working seat of the federal government and site of the president’s residence. (The Residence Act of 1790 designated the District of Columbia as the nation’s official capital, though it would not become the seat of the federal government until 1800.)

Eliza Powel was a close confidante of the first president. “Married to a twice-elected mayor of Philadelphia who served as a state senator from 1790 until his death in 1793, she was a particular favorite of the president, often ‘eagerly and passionately’ arguing politics with Washington during his tenure in the city,” writes the historian Susan Branson.8 Yet her influence extended beyond political arguments, as the celebrated Washington biographer Ron Chernow notes:

Perhaps the decisive stroke in convincing Washington to run for a second term came after a meeting with Eliza Powel that November, in which Washinton said he might resign. In a masterly seven-page follow-up letter, Powel, a confirmed Federalist, gave Washington the high-toned reasons he needed to stay in office, shrewdly playing on his anxious concern for his historic reputation. If he stepped down now, she wrote, his enemies would say that “ambition had been the moving spring of all your actions—that the enthusiasm of your country had gratified your darling passion to the extent of its ability and that, as they had nothing more to give, you would run no farther risk for them.” She warned that the Jeffersonians would dissolve the Union: “I will venture to assert that, at this time, you are the only man in America that dares to do right on all public occasions.” Evidently she managed to convince Washington, who decided to stand for a second term.9

Samuel Powel died at Powelton House, a victim of the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. His widow began building the grand mansion in May 1800. "Powelton House," as she called it, was completed in December 1801. It stood on ground bounded by present-day Race Street on the south, 32nd Street on the east, Powelton Street on the north, and Natrona Street on the west. Elizabeth Willing Powel adopted her nephew, John Powel Hare, who, in 1808, in accordance with his aunt’s wishes, changed his name to John Hare Powel (1786-1856). As a result, when she died, he inherited her enormous wealth.

In the 1830s and 1840s John Hare Powel enlarged the house until it was an enormous Greek Revival palace, but in 1851, just as soon as the Pennsylvania Railroad began to develop its 30th Street rail center, Powel sold his house and land to the railroad and never returned to West Philadelphia. The railroad partitioned the property, keeping thirty acres of low land along the Schuylkill River and selling sixty-three acres of higher ground for residential development.

Elihu Spencer Miller (1817-1879)—whose wife was Anna Emlen Hare (1833-unk.)—purchased the great house and two acres in 1860. The Miller family occupied the place until 1883, when they sold it to Evert Janson Wendell, whose building firm of Wendell and Smith demolished the house in January and February 1885. Within a year, Wendell and Smith had cut two streets through the property and constructed no fewer than 60 houses on the two-acre site. From open country estate to crowded urban streets took only 35 years.

The Bingham property to the north of "Powelton" was also rapidly developed. William Bingham (1752-1804)—a member of the Continental Congress, trustee of the University of Pennsylvania, director of the Bank of North America, and from March 1795 to March 1801, U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania—was said to be the richest American of his time.10

Bingham was also influential in West Philadelphia. he was president of the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike and it was he, "between 1792 and 1796, [who] oversaw the construction and operation of [this] major commercial artery. . . .The turnpike was modern in its engineering and crushed-stone surface and proved highly profitable as a business."11 Bingham’s daughters married sons of "Sir Francis Baring, head of the British House of Baring . . .,"12 and it was the Barings who gave Baring and Hamilton streets their names and developed the Bingham land between 1850 and 1890.

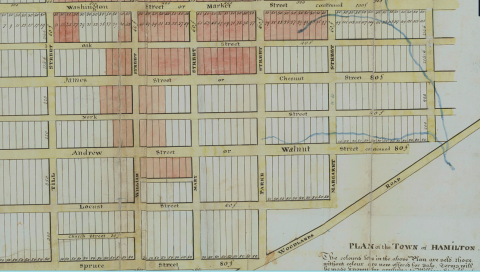

Hamiltonville

South of Market Street, William Hamilton made plans to subdivide his estate as early as 1808. In that year he formally proposed "Hamilton Village," a westward extension of the standard grid of the Philadelphia street system. The Hamilton Village development was triangularly shaped and bounded approximately by the present-day streets of Market on the north, 32nd on the east, Spruce and Woodland Avenue on the south, and 40th on the west. The streets were laid out and houses, churches, and schools began to be built. Rather than a "country" lifestyle, Hamilton Village was "suburban," that is, its residents commuted to work daily over the new Market Street bridge and returned home each evening. In that sense, Hamilton Village may be described as the first suburb of Philadelphia.

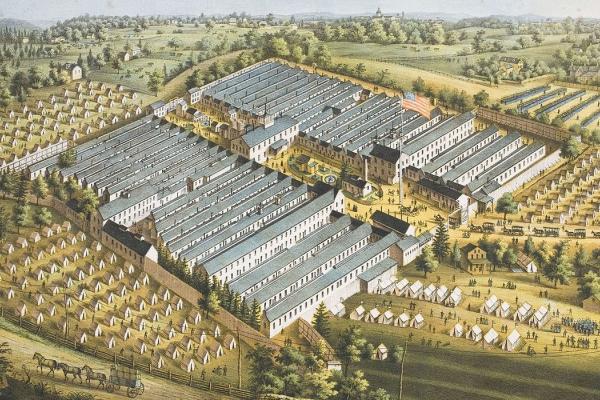

William Hamilton died in 1813 and his heirs began selling the Woodlands in large acreages. The two most important sales were those of 1829 and 1840. In the first of those years, Hamilton’s heirs sold 187 acres to "The Guardians for the Relief and Employment of the Poor of the City of Philadelphia," thereby creating in West Philadelphia a great public institution commonly known as the Philadelphia Almshouse (“Old Blockley”), which was transformed in the early 20th century to become the Philadelphia General Hospital and continued on the site until its closing in 1977.

In the second instance, in 1840, the real estate lawyer Eli K. Price and his brother, Philip, a surveyor, created the Woodlands Cemetery Company, which included the Woodlands mansion house itself and ninety-one acres of surrounding land. By 1850, at about the same time "Powelton" was sold and subdivided, the "Woodlands" as it had been was no more. Nevertheless, the mansion house has survived.

As early as the turn of the 19th century, at least one person imagined this countryside of sizable estates and fashionable mansion houses as a more cosmopolitan place.

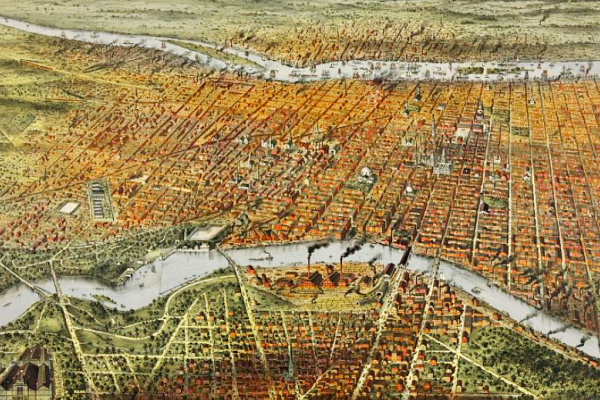

Charles P. Vare and Blockley Township

This was Charles P. Varle, a distinguished cartographer, who, in 1802, published a map for his fellow Philadelphians, entitled To The Citizens of Philadelphia This New Plan Of The City And Its Environs. Varle portrayed a fully developed version of William Penn’s rectangular city, but also a developed Blockley Township, with the street grid system of the city extended across the Schuylkill to the eastern part of Blockley and Market Street, forming a boulevard bridging the river with an esplanade at a western end in the township.

However, Varle’s dream aside, Blockley Township remained—with exceptions like Hamilton Village and Powelton Village—a rural and unpopulated district for more than a hundred years after William Warner purchased land from the Lenape and established his "Willow Grove." This is evident in the first tax assessments and censuses conducted in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Four sources provide another window on life in Blockley Township in the late 18th century. They are the records of the 1783 tax assessment, when the assessors counted the number of residents, buildings, and domesticated animals; the 1790 U.S. census; the 1798 U.S. Direct Tax; and the 1800 U.S. census.

In 1783 the tax assessors counted 644 people in Blockley Township. They also counted 85 houses, 40 barns, 119 horses, 253 horn cattle and sheep. There were two ferries, two grist mills, and one tannery in the Township of Blockley.

In 1790 the U.S. Census takers counted a 40% increase, to 883 residents (423 white males; 434 white females; 22 "other persons," that is, free African Americans; and four slaves).

In 1798, the tax assessors counted 150 houses. In 1800 the U.S. Census takers documented another 20% growth in the general population to 1,091 (549 white males; 507 white females; 33 free African Americans; and two slaves).

Blockley was only sparsely populated but growing rapidly. People lived, on average, seven to a household. Men slightly outnumbered women in these early surveys, but they dominated as property holders. In 1798 only ten of the 150 household owners were women. Official documents thus reveal Blockley Township at the turn of the 19th century as a hinterland rather than a suburb of the city of Philadelphia to the east, which had recently figured so importantly in the American Revolution and creation of a new republic.

1. “William Warner,” Craig W. Horle, Lawmaking and Legislators in Pennsylvania: A Biographical Dictionary, vol. 1:1682-1709. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991), 731–732.

4. Phillip Drennon Thomas, "Bartram, John(1699 – 1777), botanist," American National Biography Online,amb.org, accessed 11 July 2008.

5. “Bartram’s Garden: America’s Birthplace of Gardening,” visitphilly.com, accessed 15 Feb. 2008.

7. “Andrew Hamilton,” Craig W. Horle, Joseph S. Foster, and Jeffrey L. Scheib, eds., Lawmaking and Legislators in Pennsylvania: A Biographical Dictionary, vol 2: 1710–1775 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), 416–49.

8. Susan Branson, These Fiery Frenchified Dames: Women and Political Culture in Early National Philadelphia(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 35.

9. Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life(New York: Penguin, 2010), 683.

10. Robert J. Gough, "Bingham, William(1752–1804), businessman and public official," American National Biography Online, amb.org, accessed 14 July2008.