West Philadelphia in the National Eye

The construction of three major venues after 1854 put West Philadelphia in the national eye: the Satterlee General Hospital, the Philadelphia Zoo, and the Centennial Exposition of 1876.

The famous Philadelphia Zoo has been in operation since 1874, just two years before the Centennial Exposition of 1876, whose fairgrounds extended near the Zoo. Over the past 150 years, the Centennial grounds have evolved as a cultural landscape integrated into West Fairmount Park. The other venue of national importance was the Satterlee General Hospital, constructed for soldiers sick or wounded on Civil War battlefields.

Satterlee General Hospital

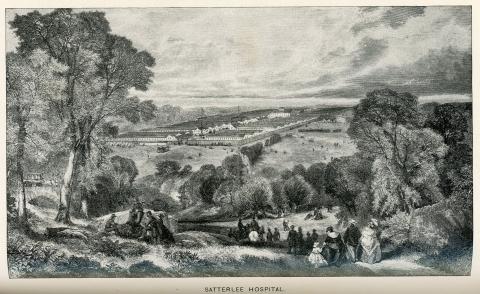

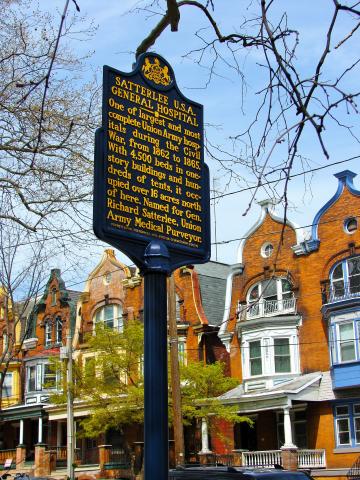

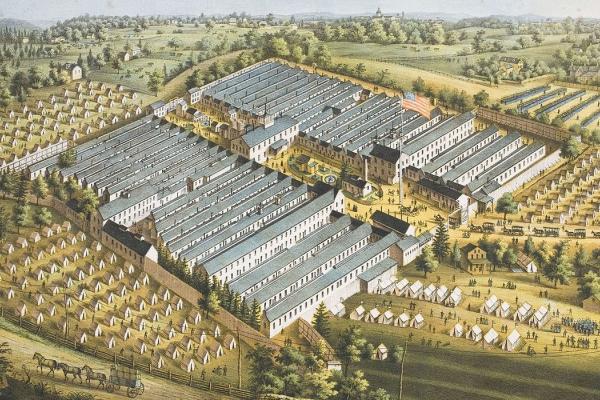

As West Philadelphia developed internally after its incorporation in 1854 into a greater Philadelphia, it also figured in major events in the nation’s history. Armed conflict never came to Philadelphia during the Civil War—although there was always the threat that fighting would spill north to the city—but West Philadelphians did experience the results of warfare directly. Satterlee Hospital, fabricated on a sixteen-acre plot bounded by present-day Baltimore Avenue and Pine, Forty-third, and Forty-sixth Streets, served as the Union Army’s largest hospital facility during the war. The West Philadelphia landscape provided an apt place for a large hospital. The Schuylkill River offered an abundant water supply and a steamboat landing at 42nd Street afforded easy access for bringing wounded soldiers to the facility.1

The United States Army built Satterlee and on May 20, 1862, Surgeon General Hammond made the request for twenty-five Sisters of Charity to take care of the wounded soldiers.2 The hospital could not have functioned efficiently without the hard work and dedication of the Sisters of Charity.3 Patients were well cared for as evidenced by mortality figures. The hospital admitted 12,773 soldiers and only 260 died. In the summer of 1862, the hospital expanded as the numbers of wounded grew. Six additional wards were built with 4,500 available beds.4 The facility closed its doors on May 27, 1864 and the area developed as a residential community, but with little reminder of the history—the suffering and humanity—that had marked the place during the Civil War.

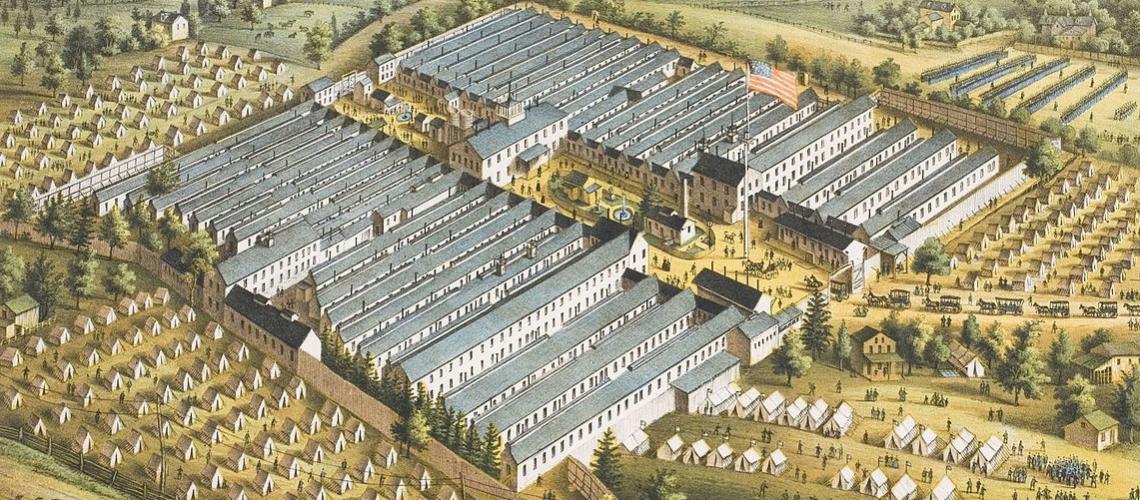

A lithograph printed in 1863 provides the following description:

This is one of the largest army hospitals in the world it is capable of accommodating 3000 men, it has two dining rooms, each 775 feet long, the whole establishment covers twelve acres of ground, and is enclosed by a fence, 14 feet high, the surgeon in charge is Doctor Isaac J. Hays, the distinguished Artic explorer, who was a former companion of the lamented Doctor Kane.5

Philadelphia Zoo

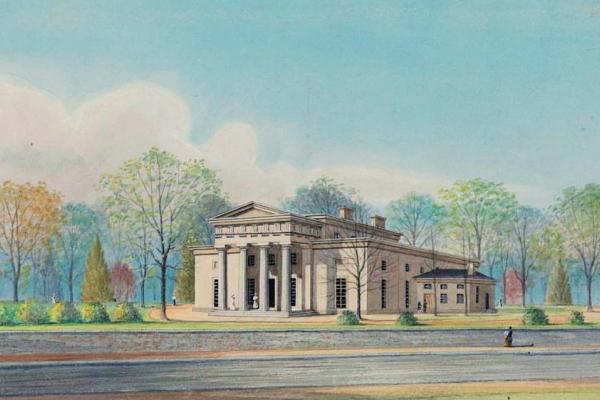

West Philadelphia soon played another kind of role in the nation’s history. The conceiving of America’s first zoo occurred on March 21, 1859, when the Pennsylvania legislature incorporated the Zoological Society of Philadelphia. The incorporation paper reads: "The purpose of this corporation shall be the purchase and collection of living wild and other animals, for the purpose of public exhibition at some suitable place in the City of Philadelphia, for the instruction and recreation of the people."6 Dr. William Camac, the first President of the Philadelphia Zoological Society, considered the West Philadelphia section of Fairmount Park as the most suitable location for the zoo. Despite encouragement from the founding members of the Zoological Society, Philadelphia residents reacted apathetically to the idea of a zoo. Not until 1872, when Camac returned from a trip to Europe, did members feel determined to launch a zoo in Philadelphia. With the help of eight members, Camac raised funds to build a zoo on thirty-three acres of land along the western banks of the Schuylkill River.7

America’s first zoo opened to the public in 1874. Visitors arrived at the easily accessible zoo grounds via horse, horse-drawn carriage, steamboat, streetcar, and foot. Most Philadelphians opted to use the steamboat—the most direct route from downtown. Steamboats departed the zoo every fifteen minutes from a dock near the Fairmount Dam.8 In the first eight months of operation, 227,557 people visited the zoo, exceeding the annual attendance of the world-renowned London Zoo, and fixing the Philadelphia Zoo in the minds of a national public.9 Five years after the opening, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine wrote about the Philadelphia Zoo: "It has the air and general appearance of long-established like institutions in Europe."10 In the late 1900s, the Philadelphia Zoo continued its success and gained recognition for its pioneering work in the study and prevention of disease in animals.

Centennial Exposition of 1876

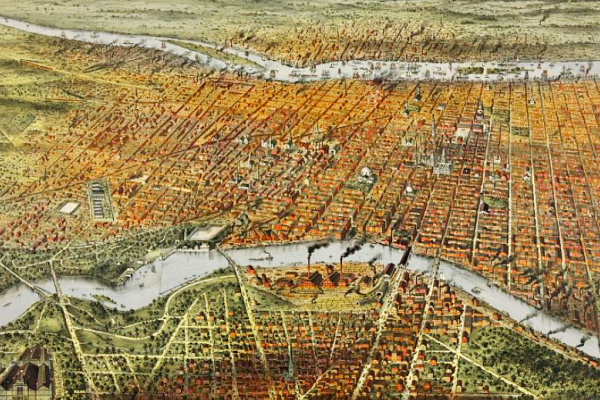

In 1876, not just national, but international attention fixed on West Philadelphia. West Philadelphia hosted on the western grounds of Fairmont Park the great Centennial Exposition celebrating the 100th anniversary of American independence.

For a full description and analysis of this transformative event in Philadelphia’s history and the development of the Centennial Exposition’s former fairgrounds and its environs as a evolving cultural landscape and catalyst for residential development over the next 150 years, see the story collection on the West Philadelphia Collaborative History website: https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/centennial-exposition-1876-evolving-cultural-landscape.

1. M. Laffitte Viera, West Philadelphia Illustrated: Early History of West Philadelphia and Its Environs, Its People, and Its Historical Points(Philadelphia: Avil Print. Co., 1903), 179.

3. "Satterlee Hospital: A Civil War Hospital in West Philadelphia," University City Historical Society.

4. Vieira, West Philadelphia Illustrated, 178.

5. Thomas Sinclair, printer, “United States Army Hospital, Philadelphia,” 1863, Library Company of Philadelphia Digital Collections.

6. As cited in Clark DeLeon, America’s First Zoostory: 125 years at the Philadelphia Zoo (Virginia Beach: Donning Company, 1999), 35.