A Streetcar Suburb in the City, 1854–1900: Part I

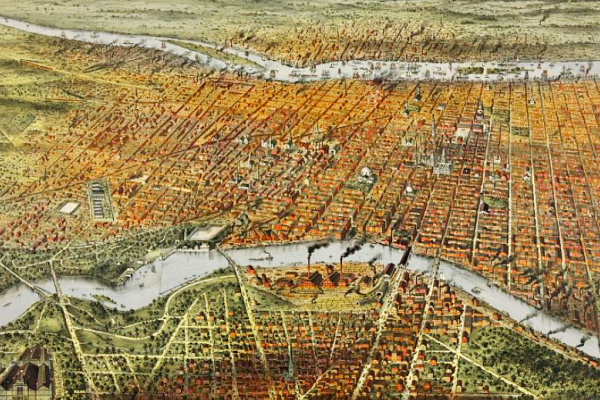

Transportation innovation and real estate development cumulated in the creation of a streetcar suburb in the city by the end of the 19th century. Part I primarily looks at the emergent neighborhoods of Hamilton Village, Powelton Village, Mantua, and Hestonville.

Transportation innovation and real estate speculation enabled a new residential West Philadelphia to emerge. By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. And even within pockets of development, the filling-in of home building occurred gradually. The primary foci of Part I are the emergent neighborhoods of Hamilton Village, Powelton Village, Mantua, and Hestonville.

Transportation innovation prior to 1854 largely aimed at connecting William Penn’s Philadelphia with agricultural settlements far west of the city. Citizens of Blockley Township were served by the four main wagonways blazed in the 1700s—Lancaster Pike heading slightly northwest, Market Street due west, and Baltimore Pike and Darby Road southwest—but these thoroughfares mainly handled the transport of farm goods from counties west of Blockley to Philadelphia via the ferries and bridges that traversed the Schuylkill River. Individual residents could travel back and forth to Philadelphia on horseback or by wagon, but the roadways were not meant for daily mass commuting. Even the Pennsylvania Railroad, which came to occupy sizable terrain in West Philadelphia, was intended for the long-distance transport of goods and people from Philadelphia to points far west.

The permanent bridges constructed across the Schuylkill in the first decades of the nineteenth century did provide the potential for commuting, and horse-drawn omnibuses soon began to carry the first commuters (who were charged substantial fares by private operators, the cost amounting to more than 10 percent of the daily wage of most workers).1 A more public-friendly form of transportation emerged after 1854, a mark of the promise of political consolidation for an expanded metropolis with efficient services (progress not handicapped, for example, by a labyrinth of political jurisdictions).

In 1865, Robert D. Work, a hat and cap merchant, bought a home in West Philadelphia at 3803 Locust Street for $5,000. Work operated a store at 51 N. 3rd Street in downtown Philadelphia, more than three miles from his new residence. Previously, he had lived on 4th Street and Callowhill, in easy walking distance to his business. Robert Work was now a commuter.2

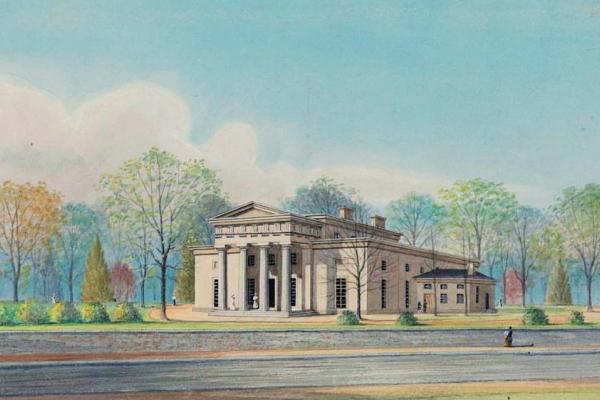

Robert Work was not the first person of means to establish a residence in West Philadelphia on a house-size lot of land at a distance from his work. As early as 1808, William Hamilton had subdivided his family’s estate to create a village of potential commuters with a grid of streets that extended on Philadelphia’s street system. By 1850, formidable mansions lined Chestnut, Walnut, Locust, and Spruce Streets between 34th and 40th Streets—with smaller row houses on the numbered streets of Hamilton Village (Robert Work’s home in West Philadelphia was built a decade before he occupied it by real estate investors Samuel A. Harrison, a tile manufacturer, and Nathaniel B. Brown, a lawyer and local landowner; they commissioned Samuel Sloan to design the Gothic Revival cottage that still stands today on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania).3

Hamilton Village had become so developed that in 1852, it could be described by local officials in these words:

As a place of residence, it may be safely said that no other location in the vicinity of Philadelphia offers superior attractions. The ground in general is elevated and remarkably healthy; the streets are wide, and may of them, bordered with handsome shade trees; a large portion of the District has been covered with costly and highly ornamental dwellings. New streets are being opened, graded, and paved; footwalks have been laid and gas introduced, and arrangements will soon be made for an ample supply of water. Omnibus lines have been established, which run constantly, day and evening, thus enabling residents to transact business in the City of Philadelphia and adjoining districts without inconvenience. A number of wealthy and influential citizens now reside in the District, and there is every indication that the tide of population will flow into it with unexampled rapidity.4

Robert Work was among the pioneer home owners of a new residential West Philadelphia and he would soon be joined by tens of thousands of others. West Philadelphia’s population stood at 13,265 in 1850 and 23,738 ten years later, on the eve of the Civil War. And then in a tenfold increase across the second half of the nineteenth century, the area’s population mushroomed to 129,110 by 1900.5 Although the great majority of these "suburbanites within a city" could afford private residences and the costs of commuting, people from all walks of life, native and foreign-born, comprised the whole. Businessmen, such as Robert Work, doctors, lawyers, and other professionals and members of the middle class claimed West Philadelphia as their home as did craftsmen and lesser skilled workers who served the better off.

A small community of 36 African American families (with their own church) had even emerged by the 1850s in Hamilton Village near 40th Street, and the African American presence in West Philadelphia would grow to 7,137 by 1900.6

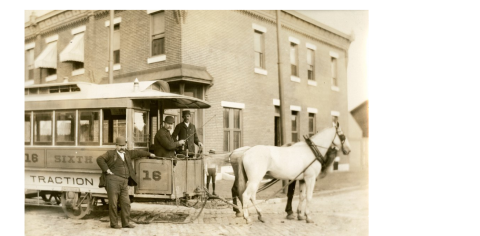

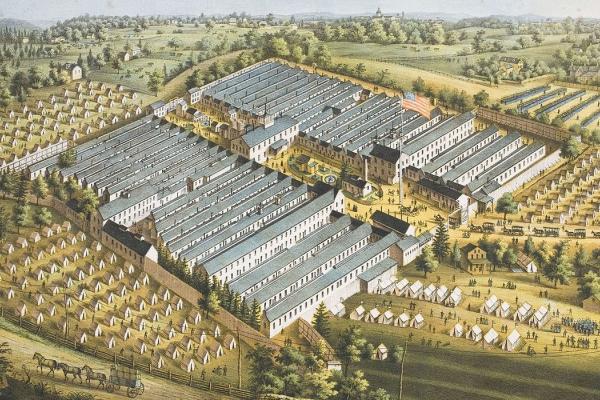

Horsedrawn Street Cars

On 2 July 1858, the West Philadelphia Passenger Railroad opened for business after the completion of the laying of tracks from 3rd Street along Market across the Permanent Bridge to 41st in West Philadelphia; further track extended north to a depot at Haverford Avenue and along Haverford to the city’s western boundary.7 Horse-drawn omnibuses on the tracks now carried numbers of passengers in a regular and swift fashion.

Within months, other lines opened serving other parts of West Philadelphia. In late 1858, the Philadelphia and Darby Railroad Company began transporting commuters along Darby Road (today’s Woodland Avenue) and the Hestonville, Mantua, and Fairmont Passenger Railway along Lancaster Pike (the former crossed the Schuylkill at Market Street, the latter at Spring Garden).

In 1866, another bridge would be built across the river at Chestnut Street. This bridge included the tracks of the Philadelphia City Passenger Railway (with the completion of a bridge at Girard Avenue in the mid-1870s—constructed to handle visitors to the 1876 Centennial Exhibition—another track-based, horse-drawn omnibus line would facilitate commuting). Although the railways ran east and west, the West Philadelphia Passenger Railroad instituted the first lateral line running north and south along 40th Street from Market to Baltimore Pike (however, to this day, public transportation routes in West Philadelphia better serve east-west travel).8

Horse-drawn wagons on tracks (horsecars) may not appear as a great innovation. Steam-powered locomotives had been suggested, but widespread opposition existed in Philadelphia to their adoption; they were considered too dangerous as sparks from the engine frequently set buildings along the tracks on fire and the speeds of the engines threatened pedestrians and animals in downtown streets.9 The horse-drawn omnibuses served the first generation of urban commuters well in Philadelphia; with their numbers relatively low due to the high cost of fares, little pressure prevailed for a mass transportation system. In the 1890s, electric trolleys would replace horses on the urban railway tracks of West Philadelphia (and other urban areas) ushering in a next stage in commuting and residential dispersion.10

Transportation innovations enabled commuting, but it was real estate developers who provided the actual lures: pleasant, stately (though not palatial) homes in pleasant environs. The developers included a host of actors: estate owners ready to divide and sell their family properties, land speculators, building contractors, building tradesmen, and government officials (the buyers of the new suburban homes can be added to the mix). Complicated financing and mortgage arrangements shaped the process.

Charles Leslie and Woodland Terrace Development

Charles M.S. Leslie provides an interesting example. In 1857, Leslie began purchasing land west of 40th Street and south of Darby Road (the future Woodland Avenue), most likely in anticipation of the completion of track construction for the Philadelphia and Darby Railroad and following the lead of Samuel Harrison, who commissioned the carpenter Samuel Sloan to design a set of elegant homes for commuters a block westward—“the western side of S. 41st Street between Baltimore Avenue and Chester Avenue”—which Harrison named Hamilton Terrace in 1856.11

Subsequent to his securing title to the land, Leslie successfully petitioned the State General Assembly to close 40th Street which at the time angled southwest through his property and lay out a new north-south street between Darby Road and Baltimore Pike (which he named Woodland Terrace). Public officials in this way played an important role in the residential development of West Philadelphia through the securing of land for street thoroughfares and their construction and maintenance, thus extending the city’s grid of streets.

Leslie worked with the architect Samuel Sloan to design 20 impressive Italianate villas along Woodland Terrace, but with a deceptive look. What appeared as single mansions were actually twin houses with separate entrances and porches on the sides. Leslie oversaw the building of the homes between April 1861 and June 1862, during the Civil War and at time of high interest rates on loans. He financed the project by temporarily selling the properties to the building contractor or even tradesmen (individual carpenters, for example). These men remained responsible for the costs of construction and could sell the buildings on their own if Leslie could not find real estate investors or direct occupiers and had to default on payment to the builders.

Risks were thus hedged, and Leslie operated as a developer without great personal investment. In spite of the complexity of financing, Woodland Terrace had a unified look and the families who came initially to live on the street were also homogeneous in social standing, the majority of households headed by merchants who owned and managed stores in downtown Philadelphia.12

Annesley Govett and Walnut Street Houses East of 34th Street

Annesley R. Govett, a lumber merchant, also developed a whole block project, but in a different manner. In 1866, he purchased land between 34th and 36th Streets and Walnut and Sansom. He parceled lots so that large homes graced Walnut Street and smaller row houses on Sansom and the numbered streets (thus appealing to different segments of the middle class). Govett then sold small numbers of lots to builders. Rather than a unified look, the streets in Govett’s plan included series of three and four homes that had different designs (ones determined by the builders)—that pattern became typical throughout West Philadelphia. Govett’s mixed-home plan shaped the social composition of the residents on Walnut and Sansom between 34th and 36th Streets. On Sansom Street in 1880, for example, bookkeepers, salesmen, and other white collar workers were among the heads of households, while on Walnut, men of more upper middle-class status, as on Woodland Terrace, owned homes.13

Charles Leslie and Annesley Govett represent unusual cases of real estate development in West Philadelphia in the second half of the nineteenth century. They initiated entire block complexes. The construction of pockets of homes by real estate investors was the norm (few developers had the means or access to credit for larger projects). The unevenness of home building—within blocks and across West Philadelphia—can be illustrated and appreciated by studying street maps and atlases of the period.

Mapping Post-1854 West Philadelphia

The detailed mapping of West Philadelphia accompanied the area’s development as a dense residential community in the last half of the nineteenth century. City agencies as well as private companies published maps for planning and insurance purposes. Several maps created during the period are particularly illustrative of the dynamics of urban growth (and can be viewed and studied macro- and microscopically in digital Maps publicly available through the Free Library of Philadelphia, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network, and the University of Pennsylvania Archives, and linked to West Philadelphia Collaborative History, as follows:

- Charles Ellet’s 1843 Map of the County of Philadelphia https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/ellet.

- S.M. Rea and J. Miller’s ca. 1851 Map of the Blockley Township https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/Islandora%3A6171.

- R.L. Barnes’ 1855 New Map of the Consolidated City of Philadelphia https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/FF-Maps_Consolidation.

- Samuel L. Smedley’s 1862 Atlas of the City of Philadelphia https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/SMD1860.Phila.031.PlateIndex.

- G.M. Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas of West Philadelphia https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/46231.

- J.D. Scott’s 1878 Atlas of West Philadelphia https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/SCT1878.PhilaWards24_27.003.MapIndex

- G. William Baist’s 1886 Atlas of West Philadelphia https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/BST1886.WPhila.003.IndexMap

- George W. and Walter S. Bromley’s 1892 Atlas of the City of Philadelphia https://westphillyhistory.archives.upenn.edu/maps/1892-atlas-bromley-24-34.

- Elvino V. Smith’s 1909 Atlas of the 27th and 46th Wards of the City of Philadelphia (West Philadelphia south of Market Street) https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/EVS1909.PhilaWards27_46.004.MapIndex.

- J.L. Smith’s 1911 Atlas of the 24th, 34th, and 44th Wards of the City of Philadelphia (West Philadelphia north of Market Street) https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/JLS1911.PhilaWards24_34_44.003.MapIndex.

Four communities are surveyed in Part I: Hamilton Village, Powelton Village, and Mantua, in close proximity to the bridges across the Schuylkill River; and Hestonville, now called Cathedral Park (though one still hears “Hestonville” in local discourse), along Lancaster Pike between 48th and 52nd Streets.

Hamiltonville (or Hamilton Village)

Ellet's 1843 Map, and then Rea & Miller’s ca. 1851 Map, reveal Hamiltonville, or Hamilton Village, a community laid out by William Hamilton in 1808, as a definitive suburban community by the mid-nineteenth century with nearly one hundred houses in the area bounded by the modern streets of 34th, Spruce, and 42nd to just north of Market Street. Plate C of Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas documented the rapid development of Hamilton Village in the twenty years between 1850 and 1870. Houses—both row and detached—lined every street in the Village and churches, public schools, and retail shops anchored the neighborhood. Two horse-drawn, trolley-car railways served the Village, one on Market Street and the other on Chestnut. Development was more intense on the north and east sides of the Village, that is, along Market Street and the numbered streets towards the Schuylkill River. While a few lots were still undeveloped, little open space remained in Hamilton Village. The direction in Hamilton Village toward full urbanization was certainly confirmed by plates 3 and 4 of Bromley’s 1892 Atlas, 27th Ward, which showed that every street was built up solidly with row, twin, and detached houses.

A few of the mid-19th century mansions survived—such as the Drexel family compound at 39th and Walnut Streets—but most had given way to smaller brick houses. The local churches and schools thrived, including the newly relocated campus of the University of Pennsylvania, which was just beginning to expand south of Spruce Street and east of 34th.

Penn’s expansion accelerated over the next twenty years as clearly evident in E.V. Smith’s 1909 Atlas. Between 1892 and 1909, Penn built eight new buildings east of 34th Street and six more south of Spruce Street, manifesting the University’s emerging dominant presence in William Hamilton’s original suburban haven. The remainder of Hamilton Village—already filled in by 1892—remained largely unchanged. Brick residences continued to be the most common form of building. A harbinger of things to come, however, was evident in the first construction of apartment houses, particularly Hamilton Court, at 39th and Chestnut Streets, and modern, multi-story hotels, including the "Normandie" at 36th and Chestnut Streets and the "Bartram" on Woodland Avenue, near the corner of 33rd Street.

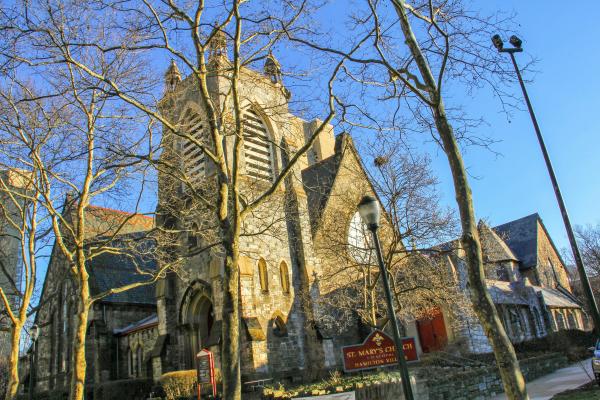

An analysis of a four-block area of Hamilton Village—bounded by present-day 38th Street on the east, present-day Walnut Street on the north, present-day 40th Street on the west, and present-day Spruce Street on the south—further helps to tell the story of the Village. At the center of this area was the intersection of 39th and Locust Streets and St. Mary’s Episcopal Church. When William Hamilton first laid out the streets of the "Town of Hamilton," he stipulated that building lots be set aside for two churches, one Episcopalian and one Presbyterian. Philadelphia’s Episcopalians responded and St. Mary’s Church was established in 1824. In the first years after the Civil War the neighborhood developed to the point that St. Mary’s congregation outgrew its original church building. In 1871 plans for the present-day building were set forth and by 1873 construction was complete.

Four-Block Sample of Hamilton Village

Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas showed sixty-three houses on the four blocks, nearly half of which were single (or detached) family dwellings on suburban-sized lots of ground. The neighborhood was served by the "Philadelphia City Horse Car Passenger Railway," which came west on Chestnut Street as far as 41st Street, and by the "Market Street Horse Car Passenger Railway," which came west on Market Street to 41st Street and then turned north on 41st Street as far as Haverford Avenue. Bromley’s 1892 Atlas showed an increase to 108 houses on the four-block area. Virtually all the new houses were twins, constructed on what had been open space in 1872. St. Mary’s continued as the only institutional presence, with no commercial or industrial use anywhere on the four blocks. Seventeen years later, the total number of houses stood at 124 and E.V. Smith’s 1909 Atlas showed the Free Library of Philadelphia’s West Philadelphia branch at the southeast corner of 40th and Walnut Streets, as well as the "Avondale" apartments at the northwest corner of 39th and Locust Streets. Though the four blocks bounded by 38th, Walnut, 40th, and Spruce Streets remained otherwise owner-occupied residential, the appearance of the first apartment house signaled an essential change, one that would steadily accelerate in the twentieth century.

Powelton (also Powelton Village)

Ellet’s 1843 Map and the Rea & Miller ca. 1851 Map indicate that Powelton, just to the north and east of Hamilton Village, was hardly developed by the mid-nineteenth century; only a handful of streets had been laid out and land had not yet been divided into building lots. The Pennsylvania Railroad had purchased a ninety-seven-acre property fronting on the Schuylkill River, but residential development would not occur until John Hare Powel began to sell his inherited estate in the early 1850s.

Change is evident in Smedley’s 1862 Atlas. Houses now lined Spring Garden Street and Presbyterians had constructed a church building at the southwest corner of 35th Street and Spring Garden. There were also houses on Hamilton and Baring streets, but fewer in number than those on Spring Garden. South of Baring, there was as yet little development.

Ten years later, Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas showed a markedly different picture. Powelton Village was now clearly outlined by the boundaries of Market Street on the south, Lancaster Avenue on the southwest, 38th Street on the west, and Spring Garden Street on the north. Within this area was a picturesque residential community of substantial single and twin houses placed on generous-sized building lots. There were, by this time, four churches serving the community: St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, a German Reformed church, a Methodist church, and the Presbyterian church. No other land use had intruded on the uniform residential development.

Baist’s 1886 Atlas and Bromley’s 1892 Atlas showed that this pattern continued to at least the end of the nineteenth century, as the building lots which remained available in the 1870s continued to be developed solely with high-end housing. Three other churches also appeared in these later years: a Baptist church, a Lutheran church, and a Roman Catholic church. For quiet, secluded living, Powelton Village was the most attractive neighborhood in West Philadelphia. Even by the time of J.L. Smith’s 1911 Atlas little had changed. A large house, however, on the east side of 35th Street, between Race and Powelton, had been converted to apartments and named "Hampton Court." Likewise, the Rush Hospital had taken the place of houses at the northwest corner of 33rd Street and Lancaster Avenue. Still, Powelton Village was virtually uniform in its residential character until the 1920s.

Four-Block Sample of Powelton Village

An analysis of a four-block rectangle at the heart of Powelton helps depict the neighborhood’s different evolution if compared to Hamilton Village. Bounded by Hamilton Street on the north, 34th Street on the east, Powelton Avenue on the south, and 36th Street on the west, this small area was anchored by the Northminster Presbyterian Church, located on the southwest corner of 35th and Baring streets. Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas showed that these blocks hosted just fourteen single family houses and sixteen twin houses. In that year, between one-quarter and one-third of the land was still open for development. Eight more twin houses were constructed by the time of Scott’s 1878 Atlas and three single houses by the time of Baist’s 1886 Atlas. When Bromley published his 1892 Atlas, the totals were twenty single family dwellings, thirty-six twin houses, and the church. Three large building lots remained. J.L. Smith’s 1911 Atlas showed twenty-four single-family dwellings, the same thirty-six twin houses, and the church. The three building lots which had been open in 1892 had been developed with single-family dwellings. In the first decades of the twentieth century, Powelton thus remained a stable, residential neighborhood with gracious homes.

Mantua

Mantua, to the north of Powelton Village, bounded by present-day Spring Garden Street on the south, Lancaster Pike on the southwest, present-day 40th Street on the west, present-day Girard Avenue on the north, and the Schuylkill River on the east, was developed in the 1830s and like Hamilton Village had taken shape by 1850. Ellet’s 1843 Map showed eight streets laid out in Mantua, with home building along the north side of Spring Garden Street and on three of the side streets. The Rea & Miller ca. 1851 Map indicated four east-west streets: present-day Spring Garden Street, Brandywine Street, Haverford Avenue, and Mt. Vernon Street. There were also nine north-south streets laid out at present-day 31st to 39th Streets. Mantua was not as well populated as Hamilton Village in 1850, but perhaps as many as fifty houses dotted the map.

Twelve years later, Smedley’s 1862 Atlas details extensive building and growth in Mantua, with additional streets north of Mt. Vernon and west of 39th. There were also churches—Episcopal, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Roman Catholic—and public schools. In 1872, Hopkins’ Atlas showed row houses being built on vacant lots, as open space began to disappear.

By 1892, Bromley’s Atlas confirmed that Mantua was fully developed, with virtually all ground spoken for. By that year Mantua was also home to three charitable and benevolent institutions: the Friends Home for Children, an orphanage at the northeast corner of Aspen and Preston Streets; the House of the Good Shepherd, which offered social services to unmarried mothers in the 3500 block of Fairmount Avenue; and the West Philadelphia Hospital for Women, which, despite its name, was a general hospital on the north side of the 4000 block of Parrish Street.

J.L. Smith’s 1911 Atlas showed a neighborhood virtually unchanged from that of 1892. Dominated by brick row houses, Mantua was also home to six churches, three public schools, and the three social service institutions just noted. Mantua emerged differently than Hamilton Village and Powelton Village just south and west; it was not suburban in character, but rather a modern urban neighborhood. Urban deterioration would also come to mark the area in the twentieth century earlier and more visibly than its two neighboring communities.

In 1872, when the City of Philadelphia selected a central location in Mantua for the new building of the Mantua Primary School, it chose the northeast corner of 38th and Mt. Vernon (then Story) Streets. The history of the four city blocks that surround this intersection is instructive in understanding the development of Mantua generally. Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas was the first to contain detailed renderings of property lines and land use. It showed that the Mantua Primary School shared its block—bounded by present-day Mt. Vernon Street on the south, 37th Street on the east, present-day Wallace Street (then Eadine or Elm Street) on the north, and 38th Street on the west—with two single or detached houses, one twin house, and ten row houses. Immediately to the south, the block bounded by Mt. Vernon Street on the north, 37th Street on the east, Haverford Avenue on the south, and 38th Street on the west, contained the building of the Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church and five detached houses, three twin houses, and eight row houses. Haverford Avenue was serviced by the "Race and Vine Street Horse Car Passenger Railway," which ran from center city Philadelphia across the Spring Garden Street bridge, through Mantua, and as far west as 41st Street and Lancaster Avenue. Looking across 38th Street to the west—the block bounded by Mt. Vernon Street on the north, 38th Street on the east, Haverford Avenue on the south, and 39th Street on the west—there was an open lot on the northwest corner of 38th and Haverford Avenue, but otherwise the block was filled with fifty-three row houses. Here was the first indication that dense urbanization had reached Mantua as early as the first decade after the Civil War. The northwest block in the quadrant was bounded by Mt. Vernon Street on the south, 38th Street on the east, Wallace Street on the north, and 39th Street on the west. This block contained four twin houses facing 38th Street, but otherwise was built up with thirty row houses. On the west end of the block were buildings of light industry, "A. Gross & Bro."

Two decades later, Bromley’s 1892 Atlas showed these four Mantua blocks squeezed to capacity, with just eight single or twin houses and no fewer than 172 row houses. The Mantua Primary School still stood on the northeast corner of 38th and Mt. Vernon Streets and the Gross family still owned the industrial buildings at 39th and Wallace Streets. The 1900 U.S. Federal census showed that the community was ethnically mixed, with Germans, Irish, Italians, and Jews living side by side in the crowded neighborhood. There were only two African American families, however, and they lived side by side in the 3700 block of Mt. Vernon Street. Ten years later, the U.S. census seemed to document a pattern of racial segregation in the neighborhood. By this time more than two dozen black families lived in these four blocks of Mantua, but all of them on the 3700 and 3800 blocks of Mt. Vernon. None of the surrounding blocks housed any African Americans. It would be interesting to know if the Mantua Primary School became segregated as well. J.L. Smith’s 1911 Atlas showed little or no physical change from 1892. The school, now called the Mantua Public School, still stood at 38th and Mt. Vernon Streets and the light industrial buildings were still present at 39th and Wallace Streets. The closely built row houses continued to define these four blocks. With the available land completely built up, investment in new housing or other buildings came to a standstill. Mantua’s identity as a crowded urban community was fully established.

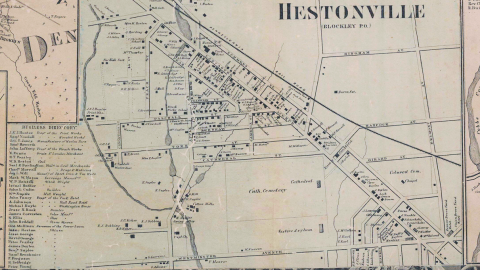

Hestonville

Transportation corridors anchored residential community building in West Philadelphia during the nineteenth century (providing a different dynamic to Hamilton Village, Powelton Village and Mantua). Development along the Lancaster Pike began almost immediately after its construction in the mid-1790s. One of the major landowners along its path through West Philadelphia was Edward W. Heston (1745-1824). Heston was a great-grandson of William Warner, the first European settler of West Philadelphia and he, Heston, inherited nearly 100 acres of land which William Penn had patented to his ancestor in the 1680s. Hestonville took shape in the early nineteenth century.

Ellet’s 1843 Map documented Hestonville as a small, crossroads community of perhaps one or two dozen buildings at the three-point intersection of present-day 52nd Street, Lancaster Pike, and the "Old Lancaster Road" (present-day 54th Street). Smedley’s 1862 Atlas contained an inset, which detailed the streets and residents of Hestonville. The village lined Lancaster Avenue from present-day 49th Street to present-day 53rd Street. The "Hestonville, Mantua, and Fairmount Horse Car Passenger Railway" came through Mantua and up Lancaster Avenue as far as a depot at present-day 52nd Street. The tollgate stood on Lancaster Avenue just above the intersection of present-day 53rd Street.

In 1862 there was little beyond the tollgate other than farm land. The main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad paralleled Lancaster Avenue on the northeast. The "Park Hotel" stood at the intersection of Lancaster Avenue and present-day 52nd Street. In 1862 there were forty buildings that fronted on Lancaster Avenue between 49th and 53rd Streets and an equal or greater number on the intersecting and adjacent streets.

Ten years later, Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas showed that Hestonville was quite built up, with nearly twice as many houses as had existed in 1862. The "Sheep Brokers Association" had taken over the depot and hotel at 52nd Street and the Pennsylvania Railroad had established a "Hestonville Depot" abutting the railroad tracks just north of 52nd Street. The Hestonville Public School now stood on the east side of 54th Street, just north of Lansdowne Avenue. The First Presbyterian Church of Hestonville occupied land on the southwest side of Lancaster Avenue between 51st and 52nd Streets. Just a few doors away stood the Fletcher Methodist Church. The built-up section of the Lancaster Pike had expanded to the southeast as far as the Rising Sun Hotel at the six-point intersection of Lancaster, 48th Street, and Girard Avenue. As the growth of housing and commerce advanced west and north from the Schuylkill River, Lancaster Avenue served as a vector, with intense development clinging to its path throughout West Philadelphia.

Twenty years later, when Bromley’s 1892 Atlas was published, development covered all five corners of the intersection of Lancaster Avenue, 52nd Street, and Lansdowne Avenue. Two streets which paralleled Lancaster, Warren to the southwest and Merion to the northeast, were also heavily developed. The Sheep Brokers Association and the First Presbyterian Church of Hestonville remained on Lancaster Avenue and 52nd, but the Fletcher Methodist Church had moved off the busy thoroughfare and relocated nearby to the quieter corner of 54th and Master Streets. Hestonville was still a distinct neighborhood, but it was being rapidly surrounded by the surging development of West Philadelphia.

J.L. Smith’s 1911 Atlas showed that the city block formerly owned by the Sheep Brokers Association, bounded by 52nd Street on the west, Merion Avenue on the northeast, 51st Street on the east, and Lancaster Avenue on the southwest, had been sold and developed with fifty-three row houses and a Philadelphia Rapid Transit power house for the new electric trolleys. One block to the southwest, the former property of the First Presbyterian Church was now occupied by St. Gregory’s Roman Catholic Church and the former property of the Fletcher Methodist Church was now occupied by the George Institute, a neighborhood library open to the public. Southeast, along Lancaster Avenue as far as 48th Street, the streetscape was a dense mix of commercial and residential. Only the Heston Public School retained the name of the community’s founder. What had once been a village unto itself was now fully engulfed by the huge urban sprawl of West Philadelphia. The force behind development, though, was the wagon-turned-rail thoroughfare of Lancaster Pike-turned-Avenue.

1. Walter Licht, Getting Work: Philadelphia, 1840–1950 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 53.

2. Roger Miller and Joseph Siry, "The Emerging Suburb: West Philadelphia, 1850-1880," Pennsylvania History 46 (April 1980): 114–115.

5. Mark Frazier Lloyd, “Notes on the Historical Development of Population in West Philadelphia,” University of Pennsylvania Archives, 2008.

6. Lloyd, “Notes on Historical Development of Population”; Miller and Siry, “Emerging Suburb,” 106–107.

7. Robert Carl Jackle, “Philadelphia Across the Schuylkill: Work, Transportation and Residence in West Philadelphia, 1860–1910” (Ph.D. diss., Temple University, 1985), 43.

8. Jackle, “Philadelphia Across Schuylkill,” 43, 93–94.

9. John Henry Hepp, The Middle Class: Transforming Space and Time in Philadelphia, 1876–1926 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 30.

11. University City Historical Society, “West Philadelphia Streetcar Suburb Historic District,” accessed from http://www.uchs.net/HistoricDistricts/wpsshd.html, 11 February 2020.