Institution Building in the 19th Century

In the 19th century, West Philadelphia saw the rise of many institutions: a private hospital for the insane and a public almshouse, institutions of higher learning, hospitals, schools, and benevolent and charitable institutions.

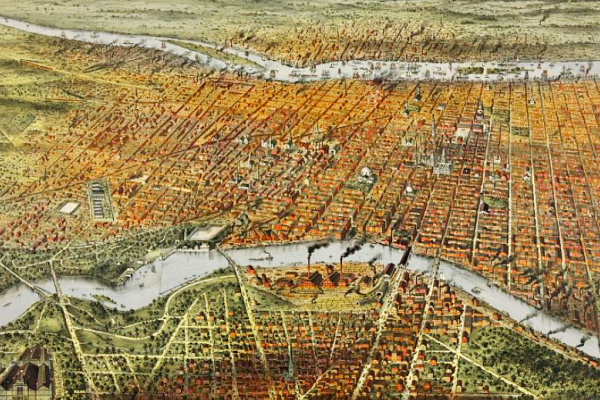

In the National Period, Philadelphia was a leader in religiously inspired innovations for the rehabilitation of indigent, criminal, and mentally ill persons. West Philadelphia was the site of two of the most prominent innovations: the Blockley Almshouse (later the Philadelphia General Hospital) and the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane. As the 19th century wore on, West Philadelphia saw the rise of institutions of higher learning (the University of Pennsylvania and the Drexel Institute), private hospitals (the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Presbyterian Hospital), communities of faith, sundry elementary schools, and benevolent and charitable institutions.

Before West Philadelphia transformed into a dense residential community, the area housed formidable institutions, such as the Blockley Almshouse and the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane. Institution building continued to be a critical facet of West Philadelphia’s history after 1854. In the late nineteenth century this involved, as in the past, the migration of institutions that had been established in center-city Philadelphia, but also the creation of entire new ones by community members. By the turn of the twentieth century, institutions of higher learning, major hospitals, a myriad of churches, public and parochial schools, and benevolent societies shared the landscape of West Philadelphia with the graceful homes and rowhouses of the area.

As the first pockets of residential neighborhoods emerged in Blockley Township in the first decades of the nineteenth century with the bridging of the Schuylkill River, another kind of development occurred at the same time—the product of social disorders in William Penn’s utopian city of Philadelphia to the east.

With growing concern for the numbers of ill, homeless, and unstable people roaming the streets of Philadelphia in the mid-1700s, Benjamin Franklin and other founders of Pennsylvania Hospital made provision for the admission of psychiatric patients when the hospital opened in February 1751 at 8th and Spruce Streets (the first hospital established in North America).1 Benjamin Rush, a physician at the hospital and a leading man of science of his age, instituted humane treatments of the insane, believing that they could be cured in bright surroundings and through recreational and occupational therapies.

The early- to mid-19th century, the National Period, witnessed a surge in Protestant revivalism—the so-called Second Great Awakening. Religion-inspired reformers, many associated with the new Whig party, effectively lobbied northern state legislatures to create what they believed were humane institutions for the rehabilitation of indigent, criminal, and mentally ill persons—individuals the reformers deemed otherwise destined to be outcasts from a rapidly industrializing society. Philadelphia was a leader in such innovations.2

Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane

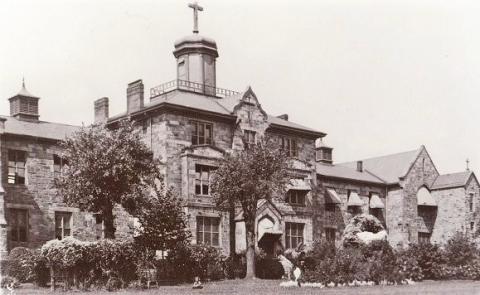

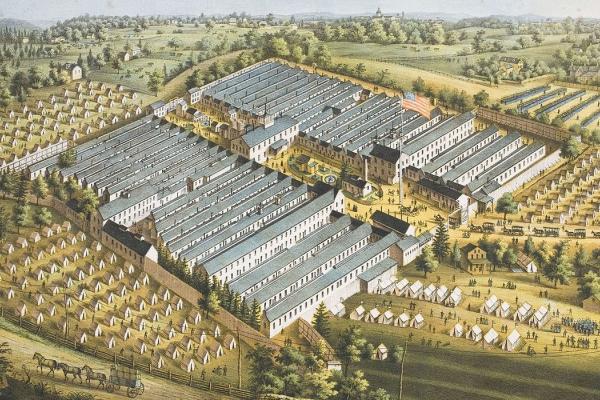

By the first decades of the nineteenth century, however, the population of psychiatric patients swelled beyond the Pennsylvania Hospital’s capacities. Hospital officials then decided to create a separate asylum in a bucolic setting, and a 130-acre tract of land was purchased in Blockley Township (at the current 49th and Market streets). The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane opened in 1841 under the progressive superintendency of Thomas Story Kirkbride, who oversaw its expansion and the construction of a formidable building complex in the late 1850s that stands to this day in the service of psychiatric care.3

During his tenure as superintendent, Kirkbride gained international recognition for his approaches to the treatment of the insane. Patients at the hospital resided unchained in private, sanitary, and well-lit rooms; worked outdoors; enjoyed recreational activities, including lectures and the use of a library; and received medical attention. The psychiatric hospital established in West Philadelphia in the 1840s, eventually renamed as the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, remained in operation until 1997, when declining revenues from insurance providers forced the closing and sale of the facility and the re-opening of a treatment center at the Pennsylvania Hospital’s 8th Street location.

The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane served private patients, those who could afford to pay the costs of hospitalization. The number of indigent, ill, and unstable people in William Penn’s Philadelphia demanded a public response as well. As early as 1684, Penn had designated two lots in his new city for the building of an almshouse for the care of what he termed the "distressed." The first almshouse established there served only Quakers. In 1731, the city opened an inclusive facility at 4th and Pine Streets—the first of its kind in North America—affording shelter, employment, and medical attention to the poor, sick, and insane who had no means of support.4

Blockley Almshouse

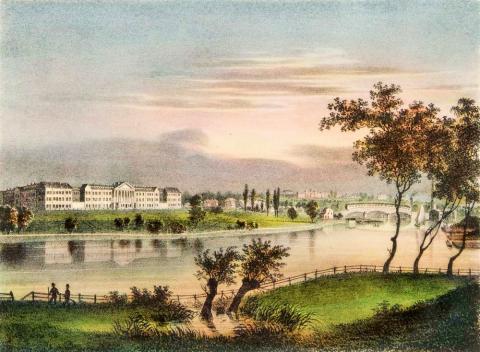

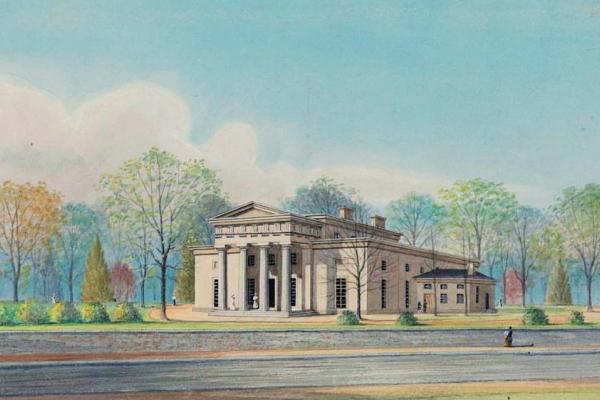

Philadelphia’s public almshouse developed as a multifunctional institute, part shelter, workhouse, orphanage, and hospital (the facility, not coincidentally, had various names associated with it—as the Philadelphia Almshouse and the Philadelphia General Hospital). Housing growing numbers of public wards, the cramped original and expanded buildings could not fill the need. In similar fashion to the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, guardians of the almshouse looked to establish a larger facility in the open, bucolic setting of the city’s hinterland. Accordingly, city officials in 1832 purchased 187 acres of the remaining Woodlands estate from the heirs of Andrew Hamilton—an area stretching from today’s 34th Street to University Avenue and Spruce Street to Civic Center Boulevard, terrain now encompassing the University of Pennsylvania.5

(For a history of the Blockley Almshouse and its evolution into the Philadelphia General Hospital, see on this website: https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/philadelphia-general-hospital-almshouse-public-hospital-and-beyond)

Institutions of Higher Learning

University of Pennsylvania: 1870–1900

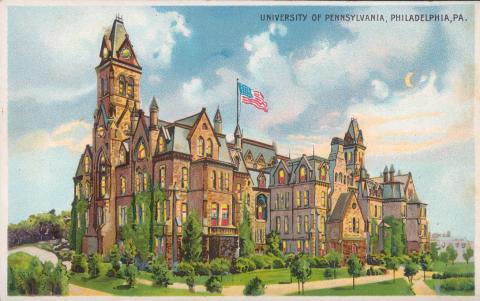

The relocation of the University of Pennsylvania to West Philadelphia after the Civil War was a key development. Benjamin Franklin had founded the University in Colonial Philadelphia in 1749 and originally located it in a single building on 4th Street, just below Arch. In 1802, looking for better facilities and more space, the trustees moved the University to the west side of 9th Street, between Market and Chestnut streets.

By the mid-1860s, however, the area around the 9th Street campus had become highly congested with commercial and industrial activity and traffic. The trustees again looked for open space and the opportunity to build better, more modern facilities. They soon decided on City-owned land at 34th and Walnut Streets, in suburban-like West Philadelphia.

The University’s partnership with the City proved very fruitful. Penn was able to expand its campus, slowly at first but significantly by the end of the 19th century. In 1870 the trustees purchased ten acres of land on Woodland Avenue, just south and west of 34th and Walnut streets. A year later they laid the cornerstone for a huge, new College Hall and in 1872 they opened the building to faculty and students.

Also. in 1872 the Trustees purchased an additional seven acres from the City, this land located at the southwest corner of 34th and Spruce Streets. There they intended to build the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. The School of Medicine now followed the College to West Philadelphia, building the second major building on campus, Medical Hall (once Logan, now Claudia Cohen Hall), which opened in 1873. The Hospital followed a year later.

Additional purchases grew the campus rapidly in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1882, the trustees acquired thirteen and one-quarter acres on the south side of Spruce Street, on the west end of the Hospital plot. This purchase nearly doubled the size of campus and provided adequate space for the Quadrangle dormitories, which were built in 1895 and 1896 at 37th and Spruce Streets.

In 1889 the University purchased another 10 acres from the City, this land located east of 34th Street and south of Walnut. Within two decades five buildings were constructed on the 1889 purchase: the Department of Hygiene in 1892 (replaced in 1996 by the Vagelos Laboratories); Franklin Field in 1895 (rebuilt in 1922, with the upper deck added in 1925); Hayden Hall in 1896; Weightman Hall in 1904; and the White Training House in 1907 (today remodeled and renamed the Dunning Coaches’ Center).

In 1890, one of the University’s great benefactors, Joseph M. Bennett, donated land and townhouses at the southeast corner of 34th and Walnut Streets with the stipulation that they be used to educate women. The trustees converted the houses to a women’s student center and dormitory and named the buildings "Bennett Hall."

In 1894 the City sold the University another eight acres, this located at the southeast corner of 34th and Spruce Streets. There the trustees built the University Museum. By the end of the century, the campus of the University of Pennsylvania extended to 50 acres and the trustees had constructed on it nearly 30 buildings.6

Thomas Webb Richards, professor of drawing and architecture, designed the first four University buildings: College Hall, Medical Hall, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Hare Laboratories, this last building erected at the northeast corner of 36th and Spruce Streets (now demolished and replaced by Williams Hall). College Hall, the first building on the University of Pennsylvania's new campus, housed all the functions of the College, including the library, classrooms, laboratories, and offices. Directly west of College Hall was Logan (now Cohen) Hall, which was built for the School of Medicine in 1873 and which later, in 1906, after the Medical School moved to Hamilton Walk, was remodeled for the Wharton School.

Frank Furness, the renowned 19th century Philadelphia architect, designed an architectural masterpiece, University Library (now renamed the Fisher Fine Arts Library), located immediately east of College Hall; it opened in 1891. Nearby, Houston Hall, the first student union in the United States, was completed in 1895.7

For full discussion of the University of Pennsylvania’s development in the 20th century, see on this website: https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/penn-and-almshouse; https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/university-of-pennsylvania#after-content-container

Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry

A newly established institution of higher learning would adjoin the re-relocated University of Pennsylvania during Penn’s building boom of the 1890s. In 1892, the doors of the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry opened at 32nd and Chestnut Streets; an old inn, the "Black Castle," and the Kean homestead had occupied the site. Anthony J. Drexel, a powerful Philadelphia financier, and George W. Childs, a well-known philanthropist, provided the initial endowment. Drexel separately donated $2 million dollars for construction of the still-standing Renaissance-style Main Building of Drexel Institute. The school aimed at improving employment prospects for both young men and women by providing technical and liberal arts instruction with day and night time classes.8

The first president of Drexel, James MacAlister served from 1891 to his retirement in 1913. MacAlister was an immigrant from Scotland and graduate of Brown University and Albany Law School. Prior to being appointed the president of Drexel Institute, he had served as the superintendent of the Milwaukee public schools and later as the first superintendent of the Philadelphia public school system; he was also a member of the board of trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. MacAlister was chosen because he believed that practical training in an industry was inherently valuable and he remained a proponent for technical and vocational education throughout his term.

During MacAlister's tenure, Drexel Institute offered courses for the public in art and illustration, mechanical arts, domestic arts and sciences, commerce and finance, teacher training, physical education, and librarianship. Drexel was the third university in America to offer training for librarians.

During MacAlister’s presidency, well known Philadelphians, such as the artist Thomas Eakins, taught at Drexel. In 1900, the curriculum was expanded with classes in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. In 1905, Drexel expanded to other buildings on Chestnut and 32nd Streets. The graduation rate also grew in the first decade of the institution and increased from approximately 70 in the early 1890s to more than 500 in 1913.

Drexel University (as it is now called) has played a valuable role in offering technical training to students from all social classes, and in the twentieth century it led the way in cooperative education programs, with students learning simultaneously in classrooms and employment settings.8

Hospitals

The placement of institutions of higher learning was new to West Philadelphia; locating hospitals there in the late nineteenth century followed earlier precedents. Two new large hospitals, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) and Presbyterian Hospital, further identified West Philadelphia with institutions for the care of the sick and injured.

As previously noted, HUP opened in 1874 on Spruce Street, situated on property purchased from the Blockley Almshouse. It was the nation’s first university-owned teaching hospital. At the same time, the University transferred its Medical School from the central city to Logan Hall, the green serpentine-stone Gothic structure built next to College Hall, on the ridge above 34th and Walnut streets. In the first half of the 20th century, HUP and the Philadelphia General Hospital would stand cheek-by-jowl.

In 1870, the same year that the University of Pennsylvania Trustees decided to move to West Philadelphia, the Presbyterian Alliance appointed a committee to investigate a site for the building of a hospital. Dr. E.D. Sanders offered his property stretching from Powelton Avenue to Filbert Street and from Saunders Avenue to 39th Street.

The next year, John A. Brown donated $300,000 to make the hospital a reality. Opened on July 1, 1872, Presbyterian Hospital operated as a charity hospital under the aegis of the Presbyterian Church. In 1875, a single-story pavilion ward was completed as a surgical ward for men. In 1878, a second pavilion opened for women.10

Presbyterian Hospital is currently part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

In another significant development, the publicly governed Blockley Almshouse was officially renamed the General Hospital of Philadelphia (PGH) in 1902.

Also notable in this history is the West Philadelphia Hospital for Women, described as follows:

Founded by Dr. Elizabeth Comly-Howell in 1889, the West Philadelphia Hospital for Women was established in order to provide a place in West Philadelphia where women could be treated by women. . . . In April 1891, the Hospital purchased a house at 4035 Parrish Street as a result of a “generous donation by Anna T. Jeanes of $10,000 from the estate of her sister, Mary Jeanes.” Another donation by Jeanes resulted in the purchase of a building on Odgen Street [next to the Hospital] for a dispensary.

In 1894, Anna P. Sharpless built and furnished an operating room and by 1903, a maternity ward was built. Almost immediately after the West Philadelphia Hospital for Women was established, a training school for nurses was begun. According to Elizabeth Peck, the first physician-in-charge who donated her services and time, "the very general testimony of physicians and patients to the character of the work done by [the graduate nurses] … convinced [the Hospital] of the value of the careful training that may be given in small hospitals.” An Auxiliary Committee, also established soon after the opening of the Hospital, aided with fundraising, donations, and support.

In 1929, the hospital merged with the Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia. At the time of the merger, it was arranged that all maternity cases would be sent to the West Philadelphia Hospital, and surgical cases would be kept at the Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia.

The Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia continued in existence until 1964 when it was absorbed by the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.11

The University of Pennsylvania and Drexel Institute were large entities with corporate charters and governance by powerful trustees. Smaller institutions also came to be situated in West Philadelphia in the late nineteenth century, many directly built by and serving community members. Houses of worship are the most notable; they became linchpins of neighborhoods, and also reflections of the ethno-religious and emerging racial diversity of West Philadelphia’s population.

Houses of Worship

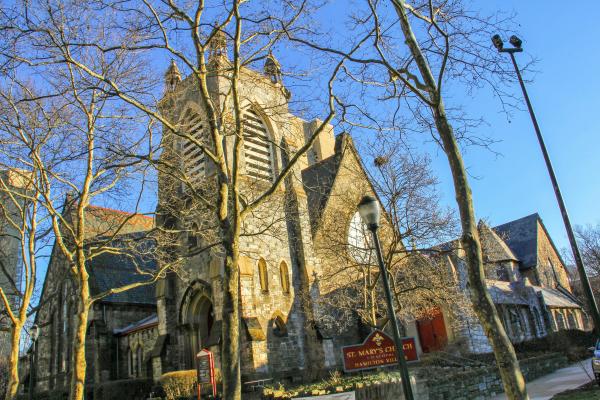

Between 1850 and 1900, more than 100 neighborhood houses of worship were built in West Philadelphia. Protestant Christians led the way with more than 70 churches, Roman Catholics added nine of their own. Among the Protestants, the Presbyterians planted 16 churches and the Episcopalians, 15. Lutherans, Methodists, and Baptists also contributed liberally to the total number.

Other Protestant churches emerged as well: a handful of German Reformed congregations; two, possibly three, African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches, serving the growing African American population in West Philadelphia, which had to practice religion separately;12 two small Quaker meeting houses; and a Reformed Episcopal church building of monumental proportions (with an accompanying theological seminary).

Non-Christians also contributed to the building of religious institutions in West Philadelphia. By 1850, Philadelphia had a relatively sizable Jewish population and Jewish people also moved to West Philadelphia as it developed residentially.13 These suburbanites in a city founded the area’s first synagogue, Congregation B’nai Israel, in the mid-1850s at 65th Street and Kingsessing Avenue.14

In 1904, a second West Philadelphia synagogue, Beth El, opened at 58th and Walnut Streets. Beth El had the largest Hebrew school in the city with more than 1,000 enrolled students.15 The synagogue also had a large sitting capacity and could accommodate 2,000 people. With a declining Jewish population, Beth El would close its doors in West Philadelphia in the 1960s and reopen in a true suburban location.

West Philadelphians built fine edifices for their houses of worship, many of architectural note. Yet, stone buildings did not necessarily translate into stability. Congregations migrated in and migrated out (as in the case of Beth El). Buildings deteriorated or were destroyed. The Protestant Episcopal Church of the Savior, for example, located at 38th Street north of Chestnut Street, opened its doors in 1855. The building featured a grand tower and spire and was considered for years the handsomest church in West Philadelphia. The congregation grew in number and the church was enlarged in 1888. However, a fire destroyed the edifice on the night of April 16, 1902, and its rebuilding would take many years.16

The Belmont Avenue Presbyterian Church, completed in 1860, suffered a different fate. The congregation lost members shortly after its inauguration. Episcopalians used the church building, but they too struggled with membership. Then, Methodists took hold of the church and soon they also experienced declining church attendance. Catholics eventually bought the church and a priest commented on the building, "Alone and forsaken it stands, a pathetic picture of old age, without friends."17

Houses of worship in West Philadelphia were, in some instances, protean institutions with changing denominations, altered spatial arrangements, and shifting ethnic and, as would be seen in the twentieth century, racial compositions.

Yet, the houses of worship built in West Philadelphia in the nineteenth century formed a thick lasting web. Tiny Hamilton Village had seven churches by 1850: St. Mary’s, Hamilton Village, Episcopal Church (1827); Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church (1827); Mt. Pisgah AME Church (1833); the African Baptist Church of Blockley Township (1826); First Presbyterian Church, Hamiltonville and Mantua (1840); First Baptist Church, West Philadelphia (1843); and St. James Roman Catholic Church (1850).

Two of the seven, African Baptist and Mt. Pisgah, notably were African American congregations. Nearby Powelton Village and Mantua had by the 1870s Episcopal, Presbyterian, Lutheran, German Reformed, Methodist, Baptist, and Roman Catholic churches, a pattern of church building replicated in other developing residential communities in West Philadelphia.18

Several churches have operated under different names at the same site for the past 150 years. One of these, Monumental Baptist Church, stands at the southeast corner of 49th and Locust streets. “Monumental Baptist Church has gone by three names: the African Baptist Church of Blockley Township (1826–1848), Oak Street Baptist Church (1884–1884), and Monumental Baptist Church from 1884 to present. The current building dates from an 1884 design by David Gendell, repaired after a fire, and a section built in 1914.”19

Perhaps the most energetic of all the dominations was the Presbyterian. Between 1840 and 1907, Presbyterians established 15 new churches in West Philadelphia. In addition, three other Presbyterian churches relocated from center city Philadelphia to West Philadelphia. Building initially in Hamilton Village, Powelton Village, and Mantua, Presbyterians immediately began expanding throughout West Philadelphia.

Presbyterians established a church at Hestonville in 1859 and another one at Haddington in 1880. In the 1880s and 1890s, as new West Philadelphia neighborhoods began to infill, Presbyterian churches seemed to spring up almost everywhere. By 1907, there were Presbyterian churches in the 3700 block of Walnut Street, in the 200 block of North 52nd Street, at the corner of Lancaster and City Line Avenues, at 42nd Street and Girard Avenue, at 60th and Master Streets, at 56th and Wyalusing Streets, on Walnut Street below 60th Street, and at 51st and Pine Streets.

Presbyterians had also established three churches marching westward along the Baltimore Avenue corridor—transportation and residential development and church building thus integral elements of the streetcar suburbanization of West Philadelphia.

The Roman Catholic church presence also grew. Beginning with St. James Church in 1850, Roman Catholics expanded their numbers and institutions in West Philadelphia over the next 75 years, gradually at first, then quite rapidly in the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth.

New churches were established near Hestonville and in Powelton Village in 1852 and 1865, respectively. In 1886 and continuing through West Philadelphia’s experience as a street-car suburb in the city, new Roman Catholic churches were built in rapid succession. A total of eight Roman Catholic churches were established in the 20 years ending in 1907 (and rapid expansion continued through the 1920s). Most of these churches also established parochial schools, thereby creating a very close-knit family experience in each parish. For West Philadelphia’s Roman Catholics, the church was even more a bedrock community institution than it was for Protestants.

Public Schools

West Philadelphia Catholic families may have preferred parochial schools, but not for the absence of widely available public schools. In 1854, at the time of the political consolidation of Philadelphia, there were only seven public schools in all of West Philadelphia. They served the existing communities of Hamiltonville, Mantua, Hestonville, and Haddington. No new public schools were built in West Philadelphia for more than a decade, but in 1866 a boom of public school building began. Twenty-seven public schools were built in the next 45 years, culminating in 1912 with the construction of West Philadelphia High School on the southwest corner of 47th and Walnut Streets. West Philadelphia High School, with two identical buildings, one for girls and one for boys, was the first neighborhood or regional high school in Philadelphia. School and church building similarly anchored residential community development in late-19th-century West Philadelphia.

Benevolent and Charitable Institutions

Finally, guided by the prominent examples of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane and the Blockley Almshouse, nearly four dozen Philadelphia benevolent and charitable institutions located or relocated in West Philadelphia in the last half of the nineteenth century. In West Philadelphia they found ample space and privacy for their specialized services.

By 1907, West Philadelphia hosted 17 institutions for "the care of children," 15 for "the care of adults and children," five for "the blind and deaf," and ten "hospitals and sanitariums." Most of these institutions were founded and funded by Philadelphia churches. Others relied on appeals to the general public.

These institutions were generally private, with restricted admissions (by age, gender, race, and medical condition), and under outside control (that is, outside West Philadelphia). Their names reflected their services, often with colorful language: the "Home of the Merciful Savior for Crippled Children," at 4400 Baltimore Avenue; "St. John's Orphan Asylum," at 49th Street and Wyalusing Avenue; the "Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Persons," at 4400 Girard Avenue; the "West Philadelphia Hospital for Women," at 4035 Parrish Street (described above); the "Pennsylvania Industrial Home for Blind Women," at 3827 Powelton Avenue; "Old Man's Home" on Powelton Avenue between Saunders Avenue and 39th Street. Initially located in the older sections of West Philadelphia, these institutions selected ever more remote areas as the nineteenth century progressed.

By 1907, open land had been taken up and institution hosting peaked. These institutions no doubt offered employment to West Philadelphians, but with the exception of the hospitals, they were not open to the public in the same manner as churches and schools.

Many of the benevolent institutions opened in West Philadelphia in the late nineteenth century provided unusual services. The Philadelphia Home for Incurables, established in 1877 at the corner of 48th Street and Woodland Avenue on a five-acre grounds, for example, provided vocational training for people with permanent disabilities. For example, a man who was born crippled without any legs below the knee and with weakened hands and arms learned the trade of printing. A man with spinal injuries similarly learned telegraphy. In the rear of the Philadelphia Home for Incurables was the Wilson Memorial, which served as a home for children who were not old enough to be admitted to the main institution. The children learned useful skills. There was a sewing hour where girls and boys learned to polish brasses or cane chairs.20

The Home of the Merciful Saviour for Crippled Children at 44th Street and Baltimore Avenue, founded in 1885, also helped crippled children learn skills and trades in areas such as telegraphy, stenography, typewriting, dressmaking, and cooking.21 The Old Man’s Home, incorporated April 20, 1864 and located on Powelton Avenue between 39th Street and Saunders Avenue, served another constituency in need,22 as did nearby Rush Hospital for Consumption and Allied Diseases at the northwest corner of Lancaster Avenue and 33rd Street (which had relocated from its original site at 22nd and Pine Streets).23 These examples manifest the range of old and new institutions that situated themselves in West Philadelphia and became part of the fabric of neighborhood life as the area developed as a streetcar suburb in a city in the late 19th century.

1. Howard Sudak, "A Remarkable Legacy: Pennsylvania Hospital’s Influence on the Field of Psychiatry," History of Pennsylvania Hospital, Penn Medicine, https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/paharc/features/psych.html, accessed 20 February 2020.

2. See Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848(New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

3. David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1971), 141–145.

4. John Welsh Croskey, History of Blockley: A History of the Philadelphia Hospital from Its Inception, 1731–1928 (Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 1929), 11–13.

6. "Profiles in Penn History: A Documentary History of Title to Penn's West Philadelphia Campus 1870-1900," University of Pennsylvania University Archives.

8. “Biographical Note,” James MacAlister Papers, Drexel University Archives & Special Collections.

9. Laffitte M. Vieira, West Philadelphia Illustrated: Early History of West Philadelphia and Its Environs; Its People and Its Historical Points (Philadelphia: Avil Printing Company, 1903), 146–151.

10. Vieira,West Philadelphia Illustrated, 163.

11. Description from West Philadelphia Hospital for Women Records, Special Collection 160, Drexel University College of Medicine Legacy Center.

12. “Mount Pisgah AME Church: Caring for the Needs of the Community,” Philadelphia Tribune, 2 December 2019.

13. Allen Meyers, The Jewish Community in West Philadelphia (Porthsmouth, NH: Arcadia Publishing Company, 2004), 10.

18. For brief histories of St. Mary’s Episcopal, Asbury Methodist Episcopal, and the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Savior, see “Churches in University City: Cornerstones of History,” University City Historical Society,” uchs.net/Churches/churches.html, accessed 22 January 2020.

19. Ashley Hahn, “Three Historic Baptist Churches Headed for Historic Designation,” 20 September 2016, https://whyy.org/articles/three-historic-baptist-churches-headed-for-his..., accessed 1-22-20.