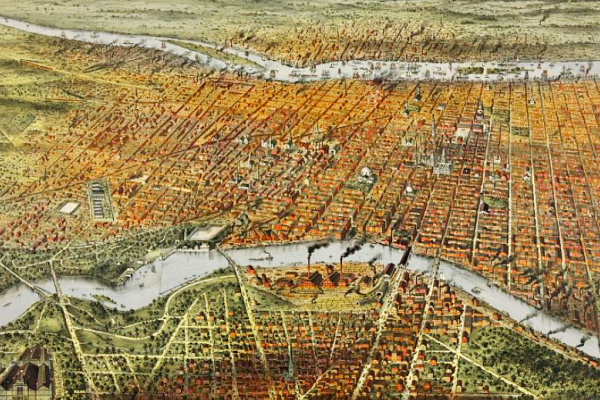

The Original People and Their Land: The Lenape, Pre-History to the 18th Century

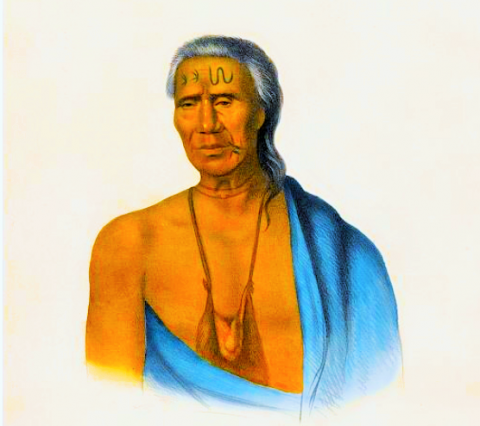

The indigenous people who inhabited the land that became Philadelphia were the Lenape (also Lenni Lenape; their English moniker was “Delaware”); they were displaced by Quakers and other religious minorities that settled the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

A nomadic people belonging to the Algonquin language family, the Lenape preceded the late 17th century European settlement of Pennsylvania by centuries. They were both hunters and agriculturalists and resided in bands along various rivers and streams. One area of their settlement was the west bank of the Schuylkill. They first encountered Europeans in the form of Dutch and Swedish settlers in the mid-17th century. From the late-17th to the mid-18th century, they were pushed westward by Quakers and other religious minorities that settled William Penn’s proprietary colony of Pennsylvania.

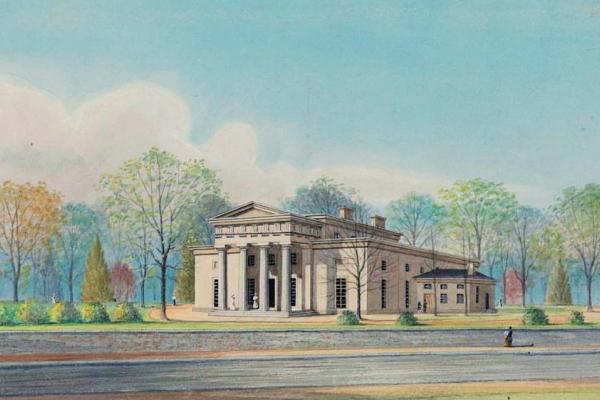

The Quaker William Warner was the first European to settle in West Philadelphia. He arrived in 1677, five years before William Penn founded his utopian city. Warner came to a vast and beautiful land filled with rolling hills, wetlands, and lush trees. The northern portions of the area were wooded with forests of oak, green pine, evergreen, chestnut, walnut, ash, button, magnolia, and hickory trees, while the meadowlands south and east were covered with moss, grass, and weeds ideal for grazing livestock. Wild berries, water lilies, strawberries, cattail, mushrooms, and corn grew wild in the fields.1

William Warner also came to a land inhabited by the Lenape or "Original People," West Philadelphia’s first natives. They were a nomadic people belonging to the Algonquian language family. Important tribes within this language group also included the Ojibwa, Blackfoot, and Shawnee. The Lenape were divided into three bands or sub-tribes: the Minsi (or Munsee, “People of the Stone Country”) inhabited the northern part of Pennsylvania, the Unami (“People Who Live Down-River”) inhabited the central region of Pennsylvania, and the Unalachtigo (“People Who Live by the Ocean”) inhabited the southern area of Pennsylvania.2 The Lenape who inhabited the land that became Philadelphia spoke the Unami dialect.3

Lenape Culture

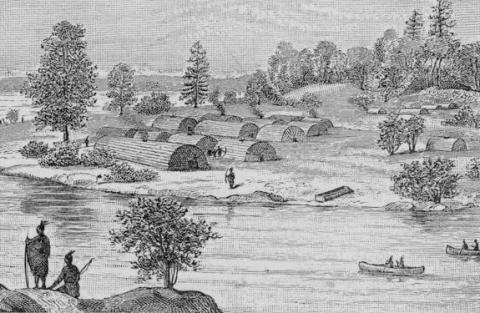

The Lenape resided in bands along various rivers and creeks. They lived on hunting and growing foodstuffs and depended on the fertility of the land. Due to their heavy tillage of the land, the soils they farmed gradually lost their productivity. As a result, Lenape frequently relocated.4 Generally, an occupied area lost its usefulness in two decades' time. Thus, the native people constantly set up, abandoned, and resettled communities throughout Pennsylvania.

Archeological evidence indicates that the Lenape inhabited the area centuries before the Europeans arrived. They established various villages along the Schuylkill River and its tributaries. Recent excavations in West Philadelphia reveal evidence of settlements along the west bank of the Schuylkill River along today’s Civic Center Boulevard.5 In 2001, a team of archeologists excavated the area prior to the building of a parking garage. During the excavation, numerous prehistoric artifacts were found, providing evidence of a fairly large and stable indigenous community occupying the area during the late archaic and early woodland periods, six thousand years ago.

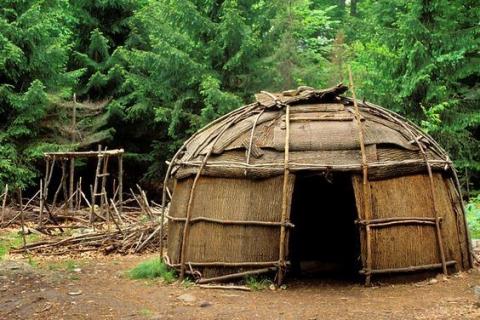

The Lenape utilized natural resources to build their homes. They lived in single doorway wooden huts called wigwams, which were situated along rivers and creeks. The size of their wigwams depended on the region they inhabited. In the southern region, the Unalachtigo’s homes were created for single-family dwellings while in the northern region larger multi-family buildings were constructed. The smaller version characterized the Lenape encampments in the Philadelphia region.

The Lenape had distinctly different physical features and appearances than that of the Europeans. Skeletal remains indicate that the average male height ranged from 5’1" to 5’7." They had oval facial structures with high cheekbones, tan skin, and broad shoulders.6 Both men and women used bear grease to dress their hair, and decorated their bodies, face, and arms with designs painted in various colors.7 The women were of medium stature. For clothing, men wore breechcloths during the summer and fur robes during the winter. Likewise, women wore wrap-around-skirts during the summer and fur robes with leggings during the winter.8 Both women and girls adorned their bodies with tribal jewelry made from shells, stones, beads, and animal teeth and claws.9

Due to their short life expectancy, men and women married young.10 Girls commonly married at the ages of thirteen and fourteen while young men married at ages of seventeen and eighteen. For some marriage lasted a lifetime, but for others this union ended in divorce. A woman wishing to divorce her husband placed all of his personal possessions outside of the wigwam. A man wishing to divorce his wife left the home.11

Once couples had children, fathers with the help of other male elders bore responsibility for teaching male children to hunt for wild game. Women taught daughters how to gather edible plants and tend to the children. In late fall, the men left their homes to hunt white-tailed deer, wild fowl, muskrat, rabbits, and foxes. Men were responsible for the heavy work around the village, making tools, weapons, mortars, frames for the wigwams, dugouts, and fishing spears.12 Tools were made from the bones of animals, wood, stone, as well as various types of grasses. Birds such as herons, pigeons, eagles, hawks, and turkeys were hunted. Once a bird was captured, it would either be prepared for direct consumption or dried. When the weather was favorable, men would use spears, harpoons, nets, and dams to catch fish. The women would clean and prepare the fish, which were either eaten raw or dried and saved for later.13

Women’s work included tanning hides, sewing, cooking, as well as gathering fruits and berries when they were in season.14 Mothers would show their daughters how to gather roots, nuts, eggs, clams, and edible plants. As they grew older, young girls learned how to garden, care for the children, and cook.15 Although corn was the main crop, several varieties of beans, squash, pumpkins, tobacco, and sunflowers were also cultivated.16 When fruit and nuts were in season, children would accompany their mothers and aunts into the forests to gather apples, persimmons, water lilies, and butternuts.17

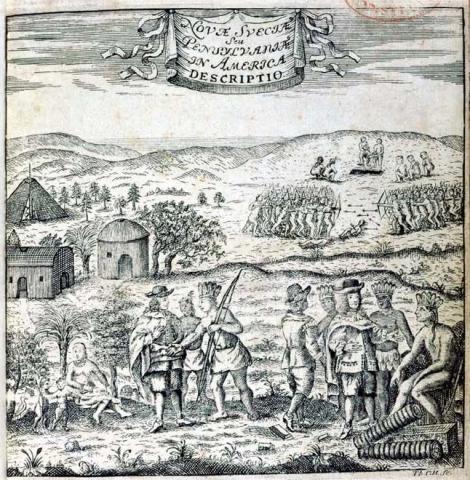

Dutch and Swedish Encounters With the Lenape

During the first decades of the seventeenth century, the harsh winds of change swept across the Lenape’s land bringing European explorers and settlers in search of commercial opportunities. In 1633, Dutch and Swedish investors, under the leadership of Peter Minuit, formed the New South Company; the Dutch had already been involved in colonization along the Hudson River. In 1638, the Company bought a tract of land from the Lenape near present-day Wilmington, Delaware. The Company then established a settlement on Tinicum Island (near today’s Philadelphia International Airport) with John Printz as governor. Swedish and Finnish settlers who engaged in fur trading followed. Further fur trading posts were established along the west bank of the Delaware River. In 1640, the New South Company came under control of Swedes as Dutch investors sold their shares. Dutch officials still had ambitions on the Delaware River and established new trading posts. In 1655, Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch Governor of New York, led an invasion capturing Swedish settlements. However, Dutch rule proved short-lived as the Dutch soon lost claims in North America to Great Britain. The Swedes remained and established a community in West Philadelphia along the west bank of the Schuylkill River bearing the Lenape name, Chinssessing, "a place where there is a meadow" (which grew to be the district of Kingsessing).

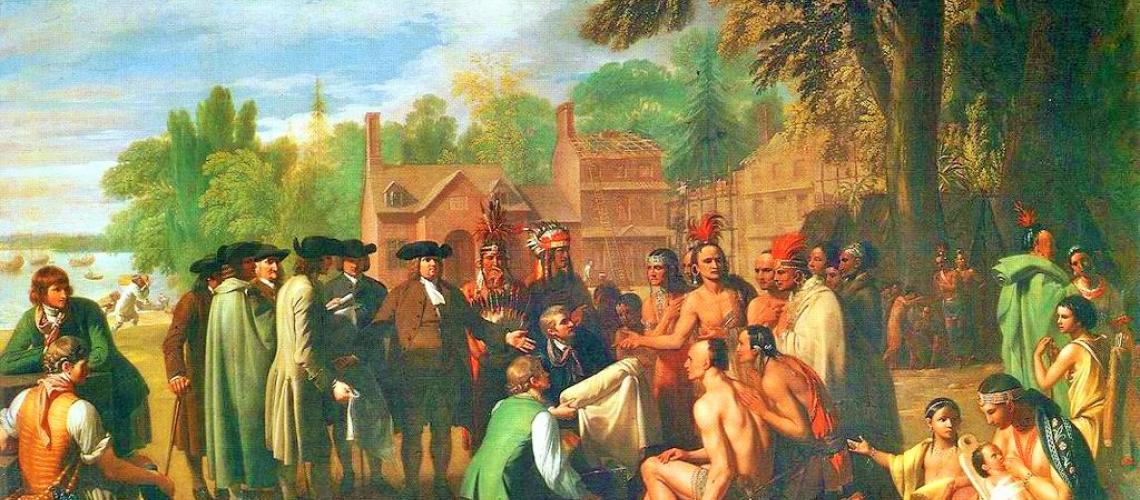

William Penn's Treaty with the Lenape

The Dutch and Swedes had episodic relations with the Lenape. The English Quaker William Penn would have more enduring and impactful interactions. In 1682, Penn came to the Delaware River valley to claim lands granted to him on a proprietary basis by King Charles II of England and to establish a haven in the New World for fellow members of the persecuted Quaker sect. He came to take possession of lands that reached throughout southeast Pennsylvania where the Lenape resided.18 The Quakers believed strongly in the principles of goodwill and friendship and Penn practiced these principles with the Lenape. Penn was determined to treat them as brothers and sisters as he believed they too were children of God. He entered into purchase agreements with the Lenape that brought lands deeded to his proprietorship under his absolute title.19 Although he took ownership rights, he still recognized and reserved certain lands where Lenape villages were located, not allowing them to be sold. Peaceful relations between the European settlers and the Lenape would disintegrate, however, not long after Penn’s death in 1718.20

The Lenape famously lost all claims to the terrain they had inhabited for centuries in the fraudulent "Walking Purchase" deed of 1737. After purchase agreements with William Penn, the Lenape moved outward, but soon these lands would be claimed by growing numbers of European settlers in the countryside around Penn’s Philadelphia. In the 1730s, Penn’s sons reinterpreted an accord that Penn had reached with the Lenape in 1686, insisting that the Penn family claim extended a full day-and-a-half’s walking distance. Sending out so-called "walkers" to determine the extent of their asserted domain, the Penn family seized ownership of lands sixty-five miles to the north and west of the earlier purchase agreements, effectively adding 750,000 acres to the family estate.21

The Delaware Tribe

The English captain Samuel Argall named the river and bay area he explored in the 1610s in honor Sir Thomas West, or Lord de la Warr III, the English governor of the struggling colony of Virginia in 1610-11. “European colonists later applied the term in varied dialectical forms to reference the Unami-speaking groups of the middle Delaware River valley, and by the late eighteenth century the term had been extended to include all of the Unami- and Munsee-speaking peoples living in or removed from the Delaware and Hudson River valleys.”22

Disperal of the Delaware

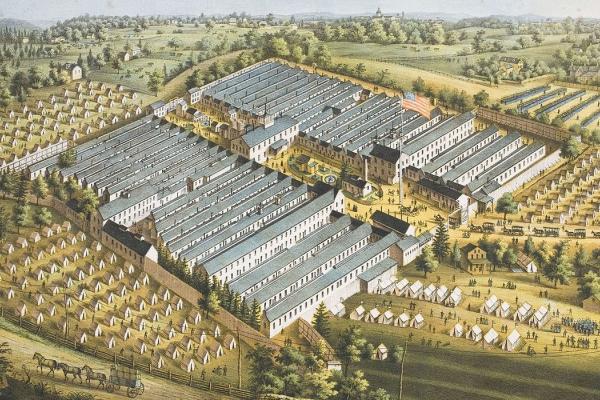

Now referred to as the Delaware (hardly an indigenous name), the Unami- and Munsee-speaking groups were increasingly pushed westward in the 18th century by the military alliance of the British and the Iroquois Six Nations.

A turning point in this history was the defeat of an intertribal coalition that included the Delaware and Shawnee, among others, at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1796 (in Ohio, Northwest Territory). Frustrated by the old Lenape custom of shared authority among multiple sachems, or chiefs, the British and Iroquois compelled the Delaware, now considered under their protection, to appoint a single chief with whom they would negotiate treaties.

After Fallen Timbers, the largest group of the Delaware were settled in Indiana, and from there were dispersed into northeastern Kansas, where they remained in the first half of the 19th century. In 1866, the federal government relocated most of the Kansas group in the Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Territory), leaving a tiny contingent in Kansas that had agreed to give up its Delaware membership.23

Today, Lenape communities are found in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Wisconsin, Ontario, and New Jersey. Since 1982, New Jersey has officially recognized the state’s Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribe, and its hometown of Bridgeton is called “Indian Town.” Ironically, Pennsylvania, once a hub of Lenapi culture, chooses to ignore this part of the state’s past.

Pennsylvania is one of a handful of US states that neither contains a reservation nor officially recognizes any native group within its borders. Pennsylvania appears to be the only state without a university-level Native American studies program or cultural center. Within state government, there are commissions on African-American Affairs. Asian Affairs and Latino Affairs, but no state agency represents or acknowledges the existence of Native Americans. Pennsylvania Department of Education standards mandate that students in the third, sixth, ninth and twelfth grade be taught about American Indians, but a survey by the authors of 10 middle and high school history books used in Pennsylvania public schools shows that none of them contains more than a sentence about the Lenape. It could be said that the Lenape have been effectively erased from the Pennsylvania landscape.24

1. Herbert C. Kraft, The Lenape or Delaware Indians (New Jersey: Lenape Lifeways, Inc., 2005), 35.

3. Bruce Obermeyer, Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation(Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2009) 37–38, 52–58; excerpted in “Removal History of the Delaware Tribe,” delaware tribe.org, accessed 9 January 2020.

4. Daniel Richter, Native Americans’ Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical Association, 2005), 28.

5. "Native American Sites in the City of Philadelphia," Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, phillyarcheology.net, accessed 20 May 2008.

6. Clinton Alfred Weslager, The Delaware Indians: A History (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1972), 59.

7. Kraft, Lenape or Delaware Indians, 11–12.

9. Herbert C. Kraft, The Lenape: Archeology, History, and Ethnography(Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1986), 129.

10. Ibid., 131.

11. Kraft, Lenape or Delaware Indians, 16.

14. Weslager, Delaware Indians, 58–62.

15. Kraft, Lenape or Delaware Indians, 20.

16. Kraft, Lenape: Archeology, History, and Ethnography, 138.

17. Kraft, Lenape or Delaware Indians, 37.

18. Weslager, Delaware Indians, 1972, 155.

21. George R. Fisher, "The Walking Purchase," Philadelphia Reflections, https://www.philadelphia-reflections.com/blog/797.htm, accessed 24 May 2008.

22. Obermeyer, Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation, excerpted in “Removal History of the Delaware Tribe.”

24. David J. Minderhout and Andrea T. Frantz, “The Museum of Indian Culture and Lenape Identity,” Museum Management and Curatorship23, no. 2 (2008): 119–133.