Incorporation into Greater Philadelphia: The Consolidation Act of 1854

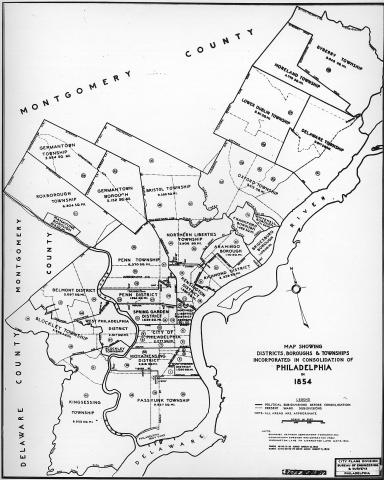

Social unrest and violence in districts due northeast and southeast of Philadelphia led to the political incorporation of these areas and Blockley (West Philadelphia) into a municipality vastly larger than William Penn’s original City of Brotherly Love.

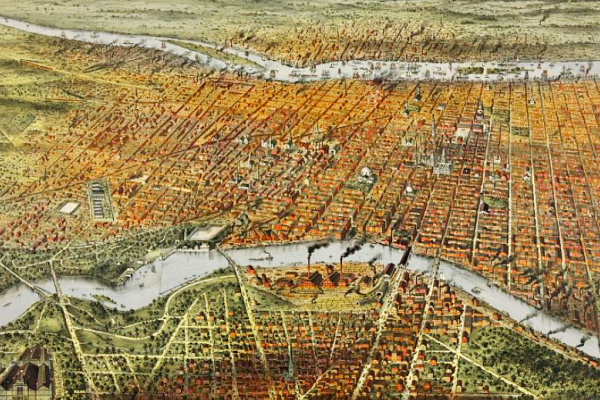

The Pennsylvania’s Consolidation Act of 1854 incorporated Blockley (West Philadelphia) into a vastly expanded City of Philadelphia. The benefits of consolidation included increased efficiencies achieved through coordinated city services, planned growth, and public works such as train stations and grand buildings—all symbolizing Philadelphia’s rising cosmopolitan stature.

The first calls for the creation of a greater Philadelphia occurred after the city was rocked by rioting in 1844 between native-born Protestants and newly arriving Irish Catholic immigrants. Labor unrest and fighting between volunteer fire brigades and other gangs in working-class communities such as Northern Liberties and Kensington to the northeast of the city and Southwark and Moyamemsing to the south had raised apprehensions in the 1830s, but the riots of 1844, largely in Kensington, demanded a response and a small chorus of civic leaders in Philadelphia suggested that greater political and policing control of the patchwork quilt of townships and boroughs surrounding the city were necessary.1

The advocates of consolidation gained little support at first. Their plan involved heavy public investments in infrastructure and raising taxes had little appeal. Many elite Philadelphians also feared annexing immigrant communities on the outskirts, especially since Democratic Party voters there would threaten the Whig Party dominance in the city. Incorporation and control by city elites gained little resonance in working-class enclaves as well.2

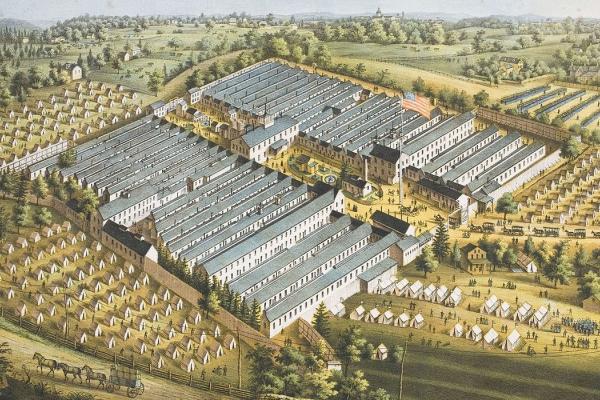

However, by the early 1850s, opinions had shifted. First, advocates of consolidation developed new justifications. Annexation, they argued and predicted, would establish Philadelphia as the commercial center of the United States. With railroads extending through Pennsylvania to western territories, the vast proportion of the goods of the West and even products from East Asia would arrive and be merchandized from Philadelphia (with Philadelphia’s manufactured products finding markets in return). Establishing appropriate transshipment facilities required the organizing of the city’s then surrounding environs (here, Blockley Township was critical in the plans of the boosters of an enlarged city).

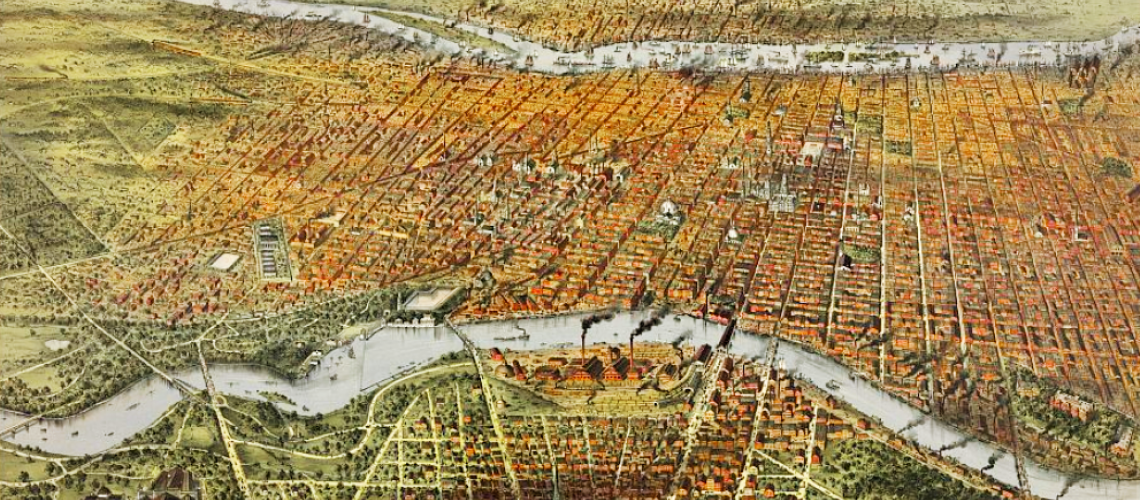

Second, increased need for coordinated police, fire, water supply, and street construction, maintenance, and sanitation services in the face of social unrest and health crises convinced once wary elite groups of the benefits of consolidation. Many of them now further understood the profits to be made in real estate development in outlying districts with planned growth. Finally, with the prospects of huge public works projects—from the building of train stations and yards and boulevards and proposed edifices that would symbolize the rising cosmopolitan stature of Philadelphia—representatives from working-class districts joined the movement on behalf of consolidation with the prospect of vast new employment opportunities. With consensus and strong advocacy, a bill to consolidate Philadelphia easily passed state assemblies in Harrisburg in 1854. William Penn’s 1200-acre city became a 122 square mile metropolis.

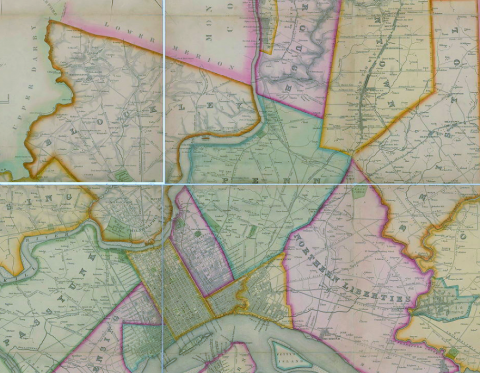

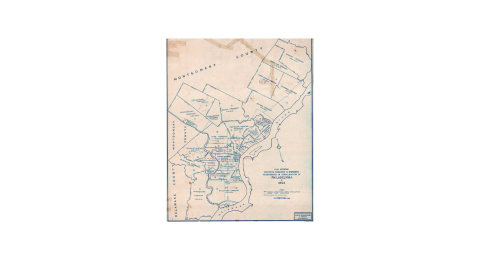

William Warner’s "Blockley" thus became identified as part of West Philadelphia as of 1854. A modern city-county map of the 1960s shows three administrative units—Blockley Township, Belmont District (on Blockley’s northern boundary), and West Philadelphia District (on Blockley’s eastern boundary)—that were part of the consolidation and would compose modern West Philadelphia. Interestingly, Charles Ellet’s 1843 map of Philadelphia County shows all of this area as Blockley Township; it is not inaccurate to simply state that Blockley Township became West Philadelphia. See Related Media for these maps.

Blockley Township had not figured in the concerns for social unrest that initially drove the movement for consolidation. But, as transportation and real estate development became an element in the call for the organizing of outlying districts of Philadelphia, Blockley loomed large. Not coincidentally, a major advocate in the political drive toward annexation was an individual who had definite property interests in the area.

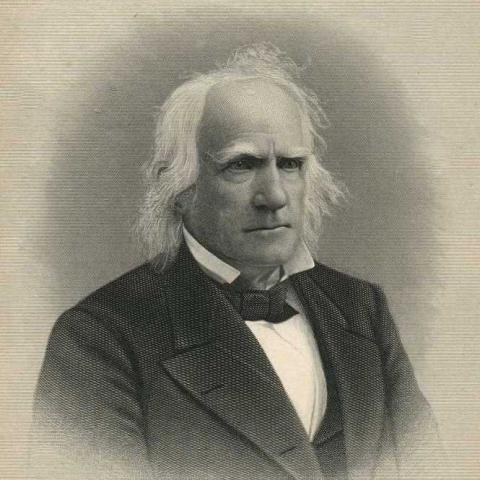

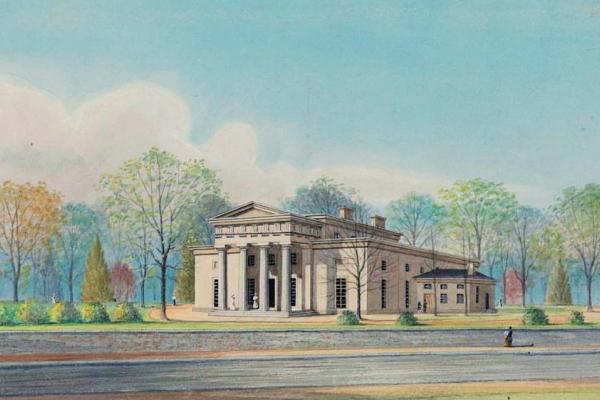

Eli Kirk Price (1797–1884) shepherded the consolidation bill of 1854 through Harrisburg as a state senator. Price was a descendent of one of the original Quaker families to settle in Philadelphia and he was a noted lawyer and political figure. Although he lived in the city, Price accumulated substantial land holdings in Blockley Township and he was one of the founding members of the Woodlands Cemetery Company.3 The extent to which Price personally profited from the consolidation is difficult to determine, but he influentially stood for a new West Philadelphia as a highly developed residential community within a major city.

1. David Montgomery, "The Shuttle and the Cross: Weavers and Artisans in the Kensington Riots of 1844," Journal of Social History 5 (Summer 1972): 411-446.

2. Andrew Heath, The Manifest Destiny of Philadelphia: Imperialism, Republicanism, and the Remaking of a City and Its People, 1837-1877 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2008).

3. Biographical notes in "Eli K. Papers," University of Delaware Library Special Collections Department, http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/findaids/price.htm, accessed 10 July 2008; “Price Family Papers,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania, http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/findaids/price.htm, accessed 20 January 2020.