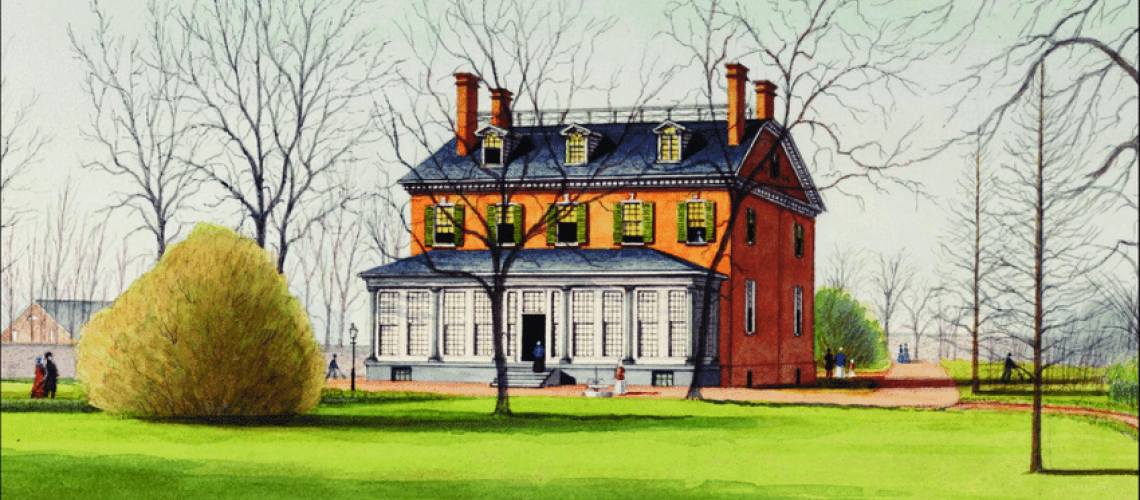

This red-brick country mansion was built ca. 1806 by the Italian-immigrant land broker Paul Busti. Busti’s 112-acre rural estate, formerly Mill Creek Farm, was known as “Blockley Retreat.” Busti’s mansion was one of many country homes that gave Philadelphia elites of the 18th and early 19th century a retreat from the congestion of the bustling city east of the Schuylkill River.

This story collection originated as “The History” component of the University of Pennsylvania Archives’ online West Philadelphia Community History Center, inaugurated in 2009 by Penn’s director of Archives, Mark Frazier Lloyd, and the Penn historian Walter Licht.

In 2009, Walter Licht, a professor in Penn’s History Department, and Mark Frazier Lloyd, director of University Archives, introduced a “virtual museum” called the West Philadelphia Community History Center. Other contributors to this effort were J.M. Duffin, Mary D. McConaghy, and Penn undergraduate history majors. In 2015–16, Devin DeSilvis, of the Graduate School of Education, directed a redesign of “The History” component of this website, a chronological narrative of West Philadelphia’s history from the time of the Lenape Indians to the formation of the streetcar suburb between 1854 and 1900. In 2020, “The History” component was incorporated as a story collection on the digital platform of West Philadelphia Collaborative History.

Stories in this Collection

A nomadic people belonging to the Algonquin language family, the Lenape preceded the late 17th century European settlement of Pennsylvania by centuries. They were both hunters and agriculturalists and resided in bands along various rivers and streams. One area of their settlement was the west bank of the Schuylkill. They first encountered Europeans in the form of Dutch and Swedish settlers in the mid-17th century. From the late-17th to the mid-18th century, they were pushed westward by Quakers and other religious minorities that settled William Penn’s proprietary colony of Pennsylvania. |

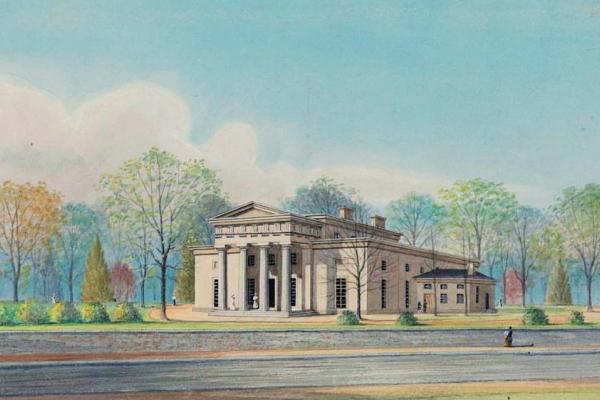

The first settlers in William Penn’s proprietary colony typically built modest log and frame houses. By the end of the 18th century large estates—with two-story brick and stone houses—had been developed along the banks of the Schuylkill River. Of note were the mansions and estates of the Hamilton and Powel families, whose names were assigned to the small villages of Hamilton (or Hamiltonville) and Powelton. |

Improvements in transportation in the first half of the 19th century included the replacement of ferries with horse-carriage and railway bridges that crossed the Schuylkill. These bridges facilitated a more efficient flow of agricultural and artisan goods between the city and its western hinterland area. The signficance for Blockley Township was economic and residential growth. |

The Pennsylvania’s Consolidation Act of 1854 incorporated Blockley (West Philadelphia) into a vastly expanded City of Philadelphia. The benefits of consolidation included increased efficiencies achieved through coordinated city services, planned growth, and public works such as train stations and grand buildings—all symbolizing Philadelphia’s rising cosmopolitan stature. |

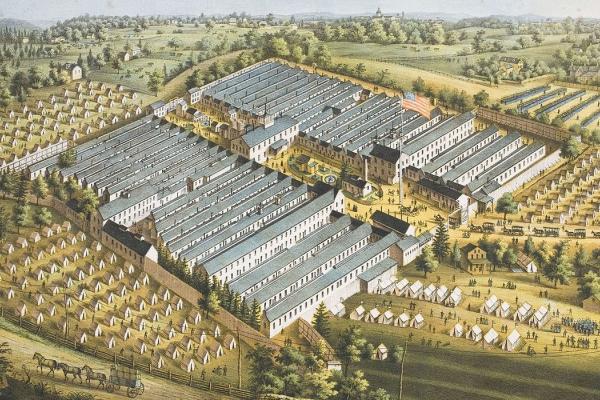

The famous Philadelphia Zoo has been in operation since 1874, just two years before the Centennial Exposition of 1876, whose fairgrounds extended near the Zoo. Over the past 150 years, the Centennial grounds have evolved as a cultural landscape integrated into West Fairmount Park. The other venue of national importance was the Satterlee General Hospital, constructed for soldiers sick or wounded on Civil War battlefields. |

Transportation innovation and real estate speculation enabled a new residential West Philadelphia to emerge. By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. And even within pockets of development, the filling-in of home building occurred gradually. The primary foci of Part I are the emergent neighborhoods of Hamilton Village, Powelton Village, Mantua, and Hestonville. |

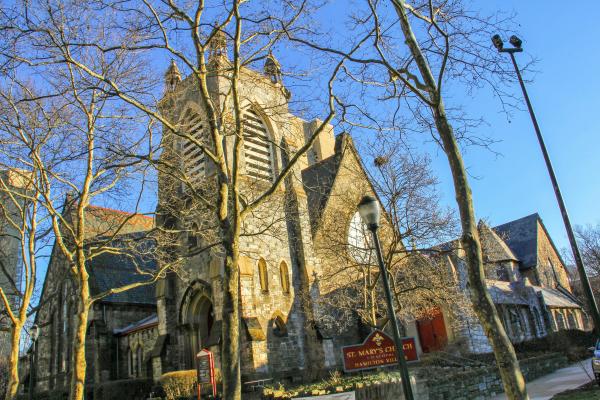

In the National Period, Philadelphia was a leader in religiously inspired innovations for the rehabilitation of indigent, criminal, and mentally ill persons. West Philadelphia was the site of two of the most prominent innovations: the Blockley Almshouse (later the Philadelphia General Hospital) and the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane. As the 19th century wore on, West Philadelphia saw the rise of institutions of higher learning (the University of Pennsylvania and the Drexel Institute), private hospitals (the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Presbyterian Hospital), communities of faith, sundry elementary schools, and benevolent and charitable institutions. |

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. And even within pockets of development, the filling-in of home building occurred gradually. Part II emphasizes the Haddington neighborhood and three other areas of residential development: 52d Street below Market, Baltimore Avenue between 43rd and 47th streets, and Satterlee Heights, east of Baltimore above 43rd. |

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. And even within pockets of development, the filling-in of home building occurred gradually. Part III looks at two little remembered, transient areas of post-Civil War West Philadelphia—Maylandville and Laniganville—and the short-lived neighborhood of Greenville. |

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. Focusing on blocks developed on the periphery of the University of Pennsylvania, Part IV highlights housing initiatives and owner-occupied mansions, some of which, in renovated form, now house university or healthcare-related activities. |

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. This article focuses on the diversity of upper-middle-class houses that sprang up around the University of Pennsylvania in the late Victorian era, highlighting the Queen Anne and Second Empire styles. |

Ten bridges spanned the Schuylkill to West Philadelphia in the second half of the 19th century. Two neighboring bridges were built in the area of Girard Avenue; new or replacement bridges were built at Spring Garden, Market, Chestnut, and Walnut streets; two other replacement bridges—one at East Falls, the other at Gray’s Ferry—were the northern- and southernmost spans. Below East Falls, a railroad bridge crossed the river. The Strawberry Mansion Bridge was the last bridge to open in the 19th century. |