Bridge Transformations: Mid- to Late-19th Century

Ten bridges linked West Philadelphia to the central city in the second half of the 19th century.

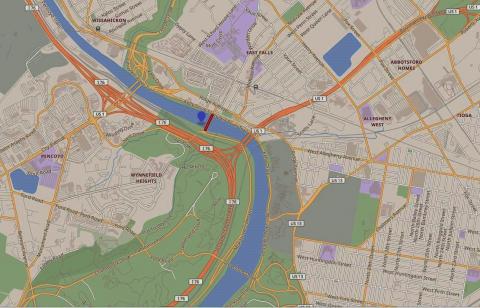

Ten bridges spanned the Schuylkill to West Philadelphia in the second half of the 19th century. Two neighboring bridges were built in the area of Girard Avenue; new or replacement bridges were built at Spring Garden, Market, Chestnut, and Walnut streets; two other replacement bridges—one at East Falls, the other at Gray’s Ferry—were the northern- and southernmost spans. Below East Falls, a railroad bridge crossed the river. The Strawberry Mansion Bridge was the last bridge to open in the 19th century.

Following the Civil War, two neighboring bridges crossed the Schuylkill River in the area of Girard Avenue.

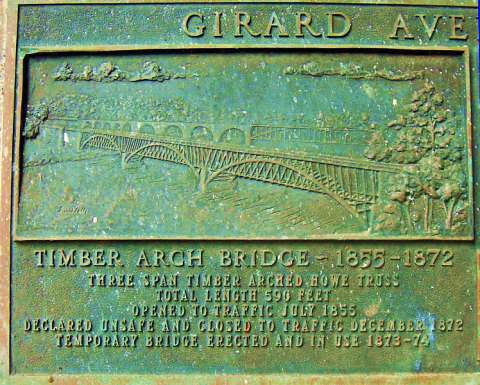

- The Girard Avenue Bridge accommodated horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians and, later, horsecar trolleys. The first version of this bridge opened to traffic in 1855. The Second Girard Avenue Bridge replaced its predecessor in 1873–74, with West Fairmount Park’s forthcoming 1876 Centennial Exposition (and millions of anticipated tourists) in mind. The bridge also provided convenient access to the newly opened Philadelphia Zoo (opened in 1874). This version was a “five span iron Pratt truss bridge,” 1,000 feet in length, 100 feet in width. The bridge’s horsecar trolley was replaced by an electric trolley in 1895. The Third Girard Avenue Bridge, the version in place today, was built in 1969–72 exclusively for vehicular traffic.1

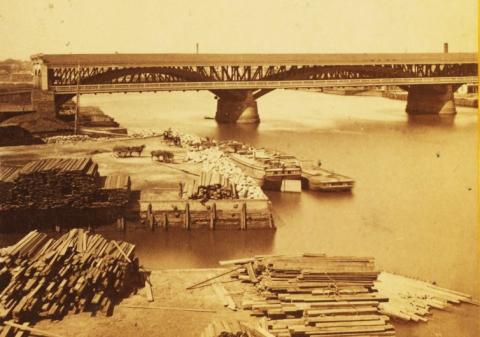

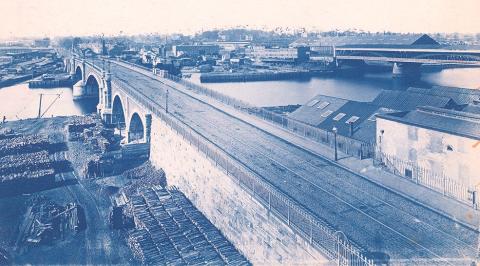

- The Pennsylvania Railroad’s Connecting Railway Bridge was constructed in 1866–67 by the Connecting Railway Company, an affiliate of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). The bridge was sold to the PRR in 1871. For four decades, the bridge stood on sets of stone arches positioned on each side of a “mid-river iron truss.” In the 1910s, the bridge was expanded to accommodate five tracks, and two massive stone arches” replaced the mid-river truss. Today this bridge accommodates AMTRAK’s Northeast Corridor rail lines and SEPTA and NJT commuter rail lines.2

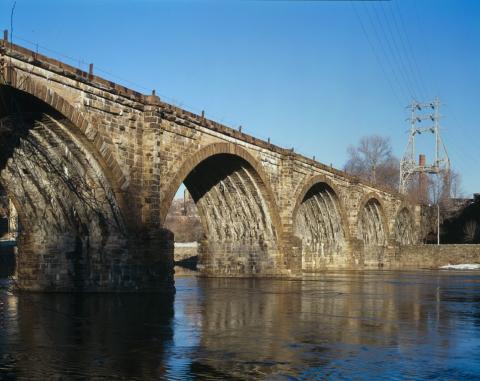

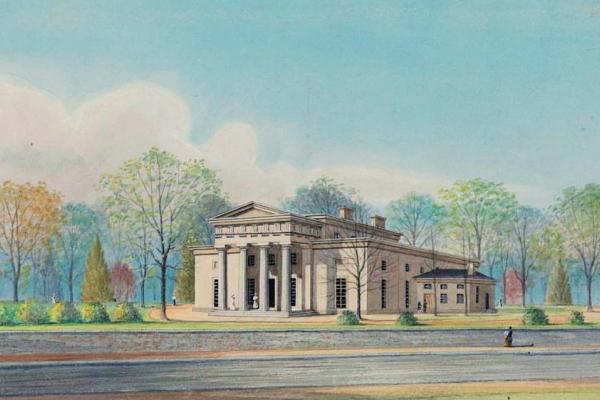

Another mid-19th century railroad bridge, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad Bridge, also known as the Schuylkill River Viaduct, and alternately as the Reading Railroad Bridge, opened in 1856 a few miles to the north of Girard Avenue. A stone arch construction, the rail viaduct conveyed coal across the river to a terminal on the Delaware River in the Port Richmond neighborhood. Rail traffic continues on the bridge in the present day.3

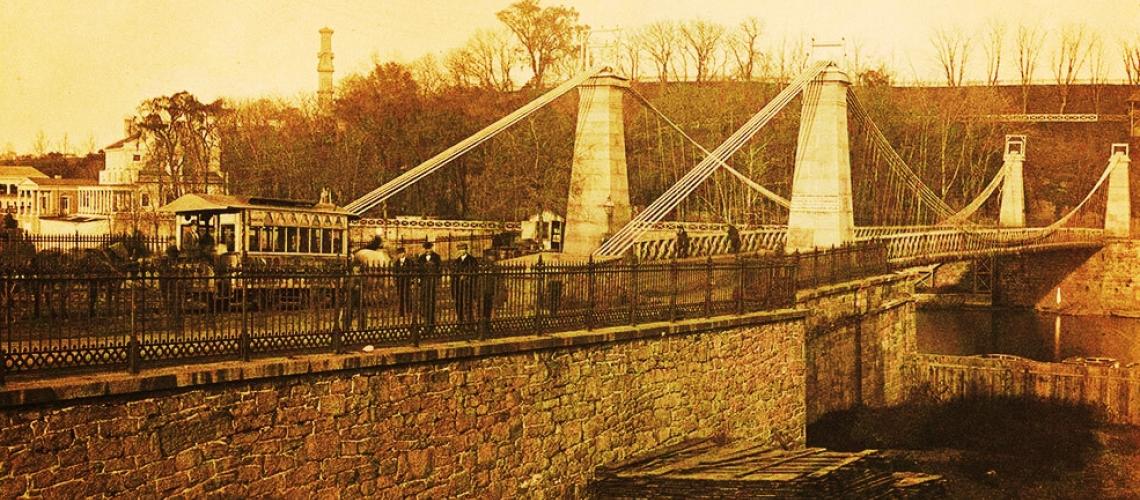

Downriver, the Spring Garden Bridge, which crossed the river just south of the Schuylkill Water Works, saw two transformations between the mid- and later decades of the 19th century. Twenty-six years after its construction in 1812, Lewis Wernwag’s scenic Spring Garden Bridge, nicknamed the “Colossus,” was consumed by fire in 1838. In 1842, it was replaced by a wire suspension bridge, the second bridge of its kind in the U.S. Designed by Charles Ellet Jr., under contract with the Philadelphia County Commissioners, the wire bridge, mounted on a stone foundation, remained a popular thoroughfare for 30 years. By the early 1870s, however, this version of the Spring Garden Bridge had badly deteriorated. It was replaced in 1875 by the third version of the bridge, a double-decker structure.4

Three bridges joined West Philadelphia to the heart of the central city: The Market Street Bridge, the Chestnut Street Bridge, and the Walnut Street Bridge.

- The Market Street Bridge evolved in four versions in the 19th century. The first bridge, named the Market Street (High Street) Permanent Bridge, had opened to traffic in 1805. The Permanent Bridge was remodeled in 1856. In 1875 a fire destroyed this bridge, which was replaced that same year with a temporary wooden structure that stood until 1888, when it was succeeded by an iron cantilever bridge. Today’s bridge, the fifth version of the Market Street Bridge, opened in 1932.5

- The Chestnut Street Bridge opened in 1866, measuring 1,528 feet, “built of cast iron, with approaches and piers of granite.” Construction of the Schuylkill Expressway in 1957 prompted bridge engineers to remove the bridge’s western pier and replace the bridge’s main spans.6

- The Walnut Street Bridge opened to traffic in 1893, described as “a 60-foot-wide concrete structure with three steel Pratt trusses mounted on four heavy oblong concrete abutments and piers.” This bridge was removed in 1988 to make way for a modern bridge mounted on the original piers.7

Two replacement bridges—one at East Falls, the other at Gray’s Ferry—were the northern- and southernmost spans of the 19th century’s ten Schuylkill bridges.

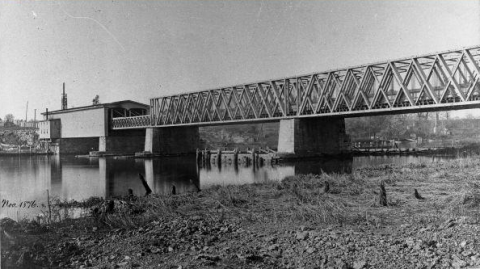

- Replacing a wooden covered bridge at the site, the steel-truss Falls Bridge opened in 1895 to connect the village of East Falls to West Fairmount Park. The proposed design was a double decker though the upper deck was never built. The carriageways shown in an 1892 drawing of the proposed bridge would become East River (now Kelly) Drive and West River Drive.8

- Roughly eight miles downriver from East Falls stood the Gray’s Ferry Bridge. In 1838, the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad (PW&B) opened a combined railroad and roadway bridge, the Newkirk Viaduct, named in honor of the company’s president Matthew Newkirk. Until 1852, the company’s steam locomotives were not allowed into the city; for these 14 years, horses pulled cars at the western end of the bridge across the river onto tracks that led to the railway company’s station at the intersection of Broad and Washington streets. From there tracks were laid to transport freight on Washington to the Delaware River docks for transshipment. Improvements, some necessitated by fire damage, marked the bridge’s progress through the Civil War and beyond. By 1889, the Newkirk Viaduct was a four-span truss bridge, 503 feet in length, with a draw bridge that retracted one of the spans into another to accommodate river traffic.

In 1880–81, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) gained control of the PW&B as the majority shareholder.

Public demand coupled with transportation innovations over the next two decades yielded a new bridge at Gray’s Ferry—1,190 feet long, with “1,660 feet of metal superstructure, with a 36-foot-wide roadway and two 10-foot-wide sidewalks”; two electrified trolley tracks on the bridge connected South Philadelphia and the Woodland Avenue’s Darby lines. The new Gray’s Ferry Bridge, which replaced the Newkirk Viaduct’s roadway, opened in 1901 and remained in service until a replacement bridge was completed in 1976. In 1902, the PW&B replaced the Newkirk Viaduct with a railroad bridge constructed beside the Gray’s Ferry Bridge. To accommodate river traffic, the new railroad bridge, named PB&W No. 1, featured a swing span that pivoted on a stone pier midway in the river. After the PRR sold the bridge to Conrail in 1976, the latter company took it out of service, let it fall to rack and ruin, and left the swing span permanently open.9

The last bridge to cross the Schuylkill in the 19th century was Strawberry Mansion Bridge, built in 1896–97 to connect East and West Fairmount Park. The Phoenix Iron Company of Phoenixville, PA, erected the steel arch truss bridge for the Fairmount Park Transportation Company (FPTC), whose trolleys crossed the bridge carrying passengers to Woodside Park, the FPTC-owned amusement park that opened on the western periphery of West Fairmount Park in the summer of 1897. The bridge also accommodated pedestrians and horse carriages. In 1946, the FPTC discontinued the trolley service; since then the bridge has been open only to vehicular and pedestrian traffic.10

1. “Girard Avenue Bridge,” Wikipedia.

2. “Pennsylvania Railroad, Connecting Railway Bridge,” Wikipedia.

3. “Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, Schuylkill River Viaduct,” Wikipedia.

4. M. Lafitte Viera, West Philadelphia Illustrated: Early History of West Philadelphia and Its Environs; Its People and Its Historical Points (Philadelphia: Avil Printing Co., 1903), 30, 33.

5. Chronology on Market Street Bridge historic marker, erected ca. 1932.

6. “Chestnut Street Bridge (Philadelphia),” Wikipedia.

7. “Walnut Street Bridge (Philadelphia),” Wikipedia.