A Streetcar Suburb in the City, 1854 – 1900: Part V

Transportation innovation and real estate development cumulated in the creation of a streetcar suburb in the city by the end of the 19th century. Part V highlights the diversity of architectural forms that characterized upper-middle-class houses around the University of Pennsylvania in the late-Victorian era.

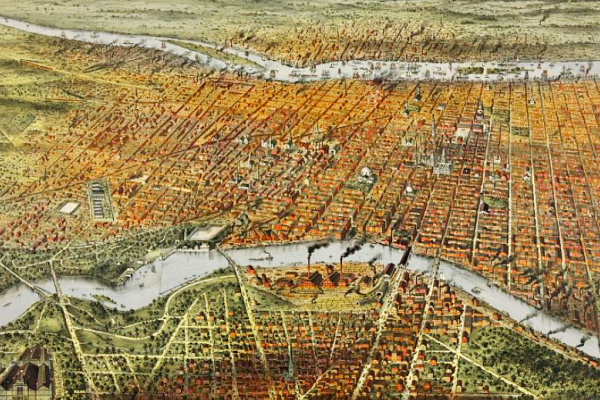

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. This article focuses on the diversity of upper-middle-class houses that sprang up around the University of Pennsylvania in the late Victorian era, highlighting the Queen Anne and Second Empire styles.

This article focuses on the diversity of upper-middle-class houses that sprang up around the University of Pennsylvania in the late Victorian era, highlighting the Queen Anne and Second Empire styles.

Blocks South of Walnut Between 40th and 43rd Streets

The 1860s saw several Second Empire brownstones rising on the 200 (east side) block of 42nd Street, built by John D. Jones. An admirer of the Italianate style as well, Jones built Italianate corner houses on each end of the block—the corner house on the southeast block of 42nd and Locust stands today as a “Victorian survivor,” with a Greek Revival porch added ca. 1910.1

On the 4100 block of Spruce Street, Samuel Sloan designed a “grouping of eight, four-story brownstone row homes . . . an early version of Second Empire style architecture.”2 This edifice is today an apartment building.

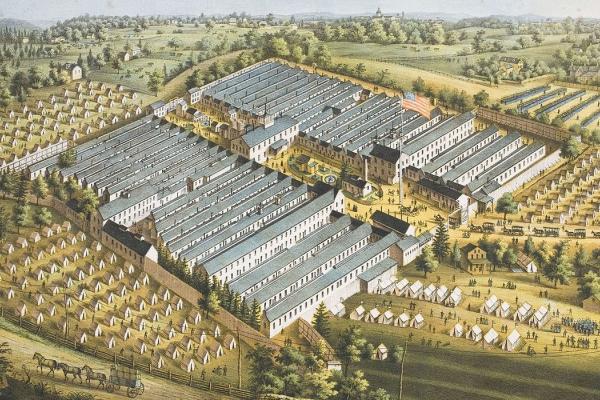

Clarence H. Clark

Clarence H. Clark is a famous name in West Philadelphia, largely because he donated the large tract of land that became Clark Park, south of 43rd Street, at the turn of 20th century. Clark, whose mansion and private park grounds (Chestnutwold, open to the public) filled the block between Spruce and Locust, and 42nd and 43rd streets, contracted with the builder John McCloskey, ca. 1873, to build redbrick Queen Ann rowhouses on property Clark owned on Locust between 40th and 42nd streets. As the nearby University of Pennsylvania had just relocated to West Philadelphia, the original purchasers may have been university employees.3

Hewitt Brothers

Fifteen years later, George W. and William D. Hewitt (Hewitt Brothers) built a row of spectacular Queen Anne houses on Spruce Street, between 42nd and 43th streets. “Done in the fashionable Queen Anne style, these houses were described as modest single homes, but in reality were purchased by the city’s growing upper middle-class,” writes the architectural historian Joseph Minardi.4 The University City Historical Society provides the following description:

These seven, three-story, red brick rowhouses are an exemplary display of the exuberance of the Queen Anne style with their columned porches with decorative brickwork and corbelling, steeply pitched gables with fishscale slate shingles, turrets, balconies, and windows with a single pane surrounded by small panes. This exquisite row is the antithesis of the bucolic suburban villas designed by [Samuel] Sloan and his contemporaries two decades earlier.5

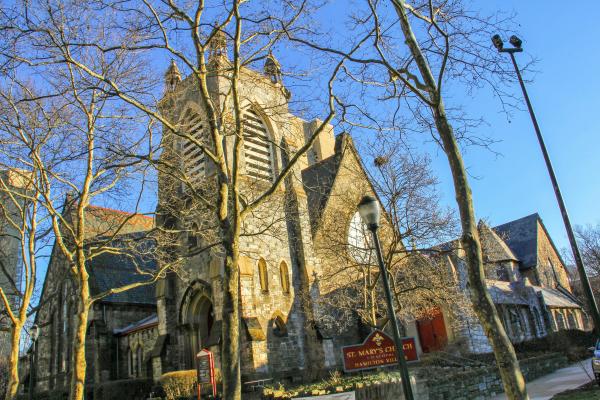

St. Mark’s Square

St. Mark’s Square, a cozy, shaded block of residences on the east and west sides of a narrow street, tucked in between Locust and Walnut streets, and 42nd and 43rd streets, dates to the 1870s. Listed in the inventory of the National Register of Historic Places, this compact block contains “thirteen, three-story, two-bay, brick, Queen Ann rowhouses.” The block’s developer was Henry C. Gibson; the Hewitt Brothers were the architects; William S. Kimball was the builder.6

The interior of the block is distinguished by “two rows of neat porch-fronted brick houses accented with black bricks.” “They have long been the home of Penn faculty members,” notes George Thomas.7

Second Empire at Penn

3643 Locust Walk

Tucked into the northeast corner of 37th and Locust Streets, at 3643 Locust on the Penn campus, is a “porch-fronted Second Empire twin,” built ca. 1873 and credited to Samuel Sloan. This historic building has served different purposes at Penn since its acquisition by the trustees in 1952 from the Omicron Association of Theta Xi fraternity, which used the Second Empire as its house. The twin was not part of the Penn campus until the 1960s, when the University extended its historic core westward to build the North Central Campus.8

In 1992 Theta Xi’s charter “was lifted by the fraternity’s national organization after a riotous party that left the house with eighteen broken windows, the latest in a string of incidents.”9

3400 Block of Sansom Street

This splendid block on narrow Sansom Street between 34th and 35th streets features “a row of eighteen Second Empire homes.” These elegant brownstones were designed by Samuel Sloan and completed ca. 1870.10

Starting in 1970, the 3400 block became a 20-year battleground for historic preservationists. The Sansom Committee was organized to thwart University of Pennsylvania planners who proposed renovating the by then deteriorating brownstones. Flush with urban renewal dollars and a planning writ for commercial redevelopment from the City and federal government (Section 112 of the 1959 Housing Act), the planners aimed to integrate the Sansom houses with a large-scale, modernist, mall-like wraparound building that would front Walnut Street and 34th Street to Sansom. The Sansom Committee represented individual owners of the brownstones who wanted to create street-level, tasteful (i.e., not “student dives” like Pagano’s and Grand’s on Walnut Street) restaurants with cozy second-floor apartments, while restoring the block’s historic bohemian ambience. After decades-long court battle, which, at one point, reached the U.S. Supreme Court, an uneasy compromise was reached that allowed Penn to build an architecturally bland, monolithic, L-shaped retail mall and office complex on Walnut Street, while giving the Sansom group control of the contested brownstones.11

Since the 1980s, upscale restaurants and shops have invigorated the 3400 block of Sansom Street. Throughout, the block has exhibited enormous vitality with street-side tables and vigorous foot traffic. The longest-lived restaurant is the celebrated White Dog Café, which John Puckett and Mark Lloyd describe as follows:

Wicks’s White Dog Café [was] the jewel in the crown, a restaurant that became nationally famous in the 1990s. The café’s moniker honored the block’s colorful history: “The White Dog got its name from a 19th-century mystic and founder of the Theosophical Society named Madame Helene Blavatsky, who once resided in the Sansom Street building and claimed to have been cured of a serious illness by having a white dog lie on her.” Wicks later opened the Black Cat Boutique in an adjoining brownstone, with a passageway connecting the two businesses.12

1. University City Historical Society, “West Philadelphia Streetcar Suburb Historic District”; Joseph Minardi, Historic Architecture in West Philadelphia, 1789–1930s (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2011), 88–89. Minardi’s splendid book is an indispensable resource for this article.

2. Minardi, Historic Architecture in West Philadelphia,” 84.

3. Roger Miller and Joseph Siry, “The Emerging Suburb: West Philadelphia, 1850–1880,” Pennsylvania History 47, no. 2 (April 1980): 137–38; Minardi, Historic Architecture in West Philadelphia, 78.

4. Minardi, Historic Architecture in West Philadelphia, 85.

5. University City Historical Society, “West Philadelphia Streetcar Suburb Historic District,” accessed from uchs.net/Historic Districts/wpsshd.html, 9 March 2020.

6. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Register of Historic Places, “National Register District Inventory for Saint Mark’s Square,” accessed from www.uchs.net/HistoricDistricts/inventories-html/stmarks.html, 9 March 2020.

7. George E. Thomas, University of Pennsylvania: The Campus Guide (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002), 177.

8. University of Pennsylvania Archives, “Mapping Penn: Land Acquisitions 1870–Present,” accessed from https://maps.archives.upenn.edu/MP/map.php, 9 March 2020.

9. John L. Puckett and Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2015), 210. The twin is now home to Penn’s Women’s Center, an organization founded in 1973.

10. Minardi, Historic Architecture in West Philadelphia, 63

11. Puckett and Lloyd, Becoming Penn, 63

12. Ibid., 233; Puckett and Lloyd quote from John Caroulis, “Of Dirty Drugs and White Dogs: The Evolution of Dining (Fine and Otherwise),” Pennsylvania Gazette, April 1997, p. 32.