A Streetcar Suburb in the City, 1854–1900: Part III

Transportation innovation and real estate development cumulated in the creation of a streetcar suburb in the city by the end of the 19th century. Part III focuses on two little-remembered, transient areas of post-Civil War West Philadelphia—Maylandville and Laniganville—and the short-lived neighborhood of Greenville.

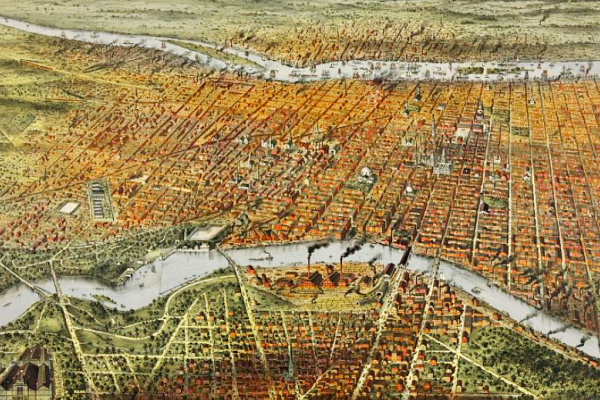

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. And even within pockets of development, the filling-in of home building occurred gradually. Part III looks at two little remembered, transient areas of post-Civil War West Philadelphia—Maylandville and Laniganville—and the short-lived neighborhood of Greenville.

Here we take up a different aspect of West Philadelphia’s emergence as a streetcar suburb in a city, looking at two little-remembered, transient areas of post-Civil War West Philadelphia—Maylandville and Laniganville—and the short-lived neighborhood of Greenville.

Maylandville

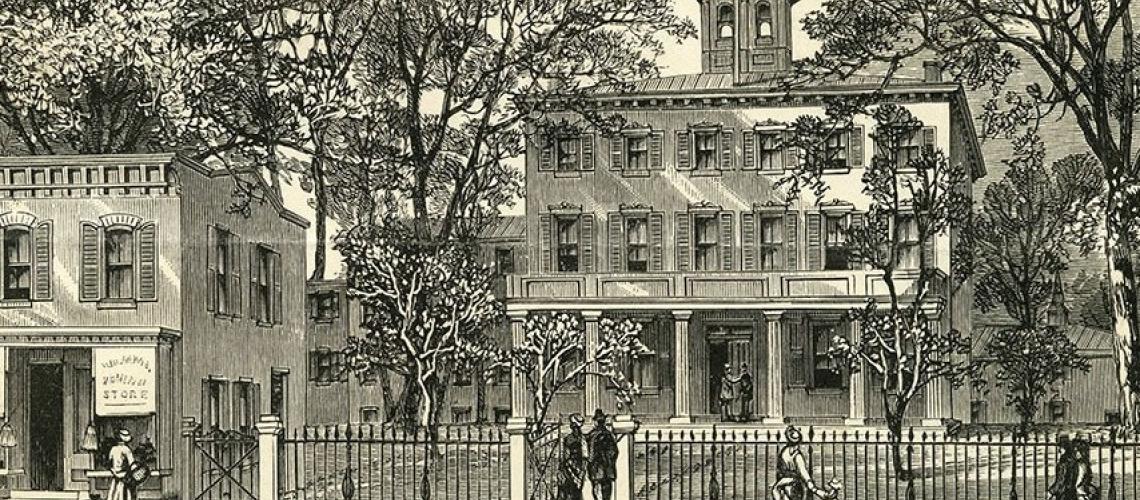

Maylandville was the name given to a small village that emerged in the 1850s in the area of Mill Creek southwest of the Woodlands Cemetery. The village was named for Jacob Mayland, who from 1817 operated a sawmill on Mill Creek, a fast-moving stream that met the Schuylkill River at 42nd Street. Mayland’s sawmill and a paper mill along the creek attracted settlers in numbers sufficient to build the Trinity Church of Maylandville in 1853.

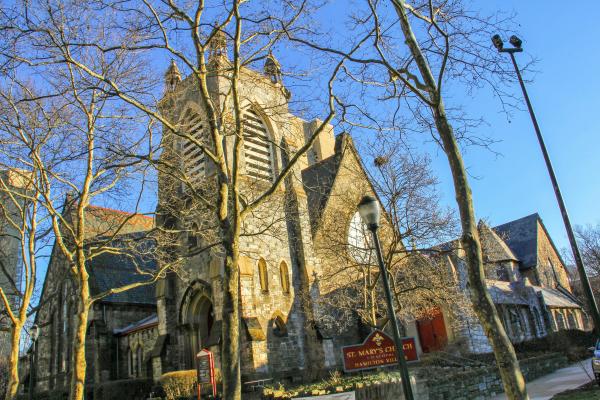

Leon Rosenthal noted in his 1963 A History of Philadelphia's University City: "By 1881, the centre of population had moved to the northward so that a new church building was erected on the northeast corner of 42nd Street and Baltimore Avenue.”1 The denomination served by Trinity Church at this new location was Protestant Episcopal. In 1890, Trinity’s parish “enigmatically” merged with the parish of St. Phillips Protestant Episcopal Church, and the Baltimore Avenue church adopted the name St. Phillips.2 "Later the building was occupied by the Woodland Presbyterian Church,” according to Rosenthal. “When the latter congregation moved to its present building on the southeast corner of 42nd and Pine Streets, the old building became the present home of a Pillar of Fire Church."3 (Today the venerable church building is home to the Covenant Community Church and the City School at Spruce Hill, a private institution.)

Rosenthal also noted: "With the passing of waterpower and the conversion of [Mill Creek] into a sewer, the mills passed from the scene and the village became absorbed in the expanding city."4 Writing in 1930, the sociologist W. Wallace Weaver described Maylandville as "one of the most miserable and unsightly areas of all West Philadelphia," lying "west of the railroad tracks along the Schuylkill River below Woodlands Cemetery, "located along Woodland Avenue and to the south as far as Forty-Sixth Street." Wallace noted the "squalor" of the neighborhood's southeastern sector, which was populated by poor black and poor white families. While he also noted, approvingly, the Breyer's Ice Cream factory and the College of Pharmacy along Woodland, as well as "prosperous homes" on 45th Street and Clark Park's frontage on Woodland, the tone of his short description of Maylandville was dismissive.5

Laniganville

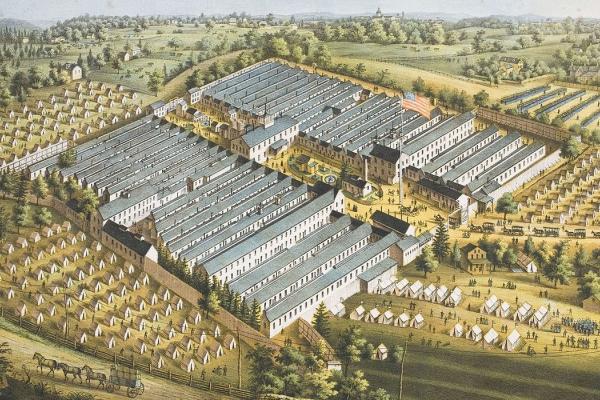

Laniganville was more a Wild West shantytown than anything resembling a streetcar suburb. This boisterous neighborhood, which never appeared on any city map, occupied the clay bluffs and depression south of Girard Avenue, above the Zoological Garden. Poplar Street and Wyalusing Avenue are mentioned in Weaver’s 1930 account, which provides the following description:

It was made up partly of squatters, who erected filmsy shacks without any pretense of securing title to the land, and a few who owned or rented homes of a curious “bandbox” construction. The first settler was Pat Lanigan, and his neighbors were largely peasant Irish of a clannish and disorderly tradition. The settlement maintained a form of independent existence as late as about 1890 with an unofficial government consisting of a mayor, aldermen and police force. . . . If [the mayor] became officious and attempted to enforce the law, he was likely to be promptly ousted. In case of serious brawls, in which men were occasionally killed, the city police were called in, but since several houses were “speakeasies,” and a number of the inhabitants were criminals, the populace favored a regime of laissez faire.6

Laniganville’s heyday was the last two decades of the 19th century. In 1894, The Times(Philadelphia) described the denizens of Laniganville as “mostly of Celtic [Irish] origin . . . a self-contained class, almost morbidly indisposed to encourage an intimacy with strangers.”Of gristly interest, one resident told the newspaper reporter: “Well, yer see, Lanigan was takin’ to liquor, poor mon, and one day when had a good full load on he fell off the Ge-rard [Girard] avenue bridge. Well, that was the end of Laniganville.”7

The Pennsylvania Railroad’s turn-of-the-century expansion and the development of the Parkside neighborhood below Girard Avenue west of the Zoo erased all traces of Laniganville.8

Greenville

Located along Market Street from 32nd to 40th Street, Greenville appeared on city maps until around 1890, though its history is “obscure.” Writing in 1930, the sociologist William Wallace Weaver wrote that the Market Street corridor in Greenville “was formerly marked by a number of stables for horses, of which ‘Connolley’s Horse Bazaar’ is a well-known survivor. There is still the atmosphere of the equestrian about the locality, but in place of blooded racers, riding academies and race tracks it is now a resort for draft horses, broken-down nags and wagon yards.”9

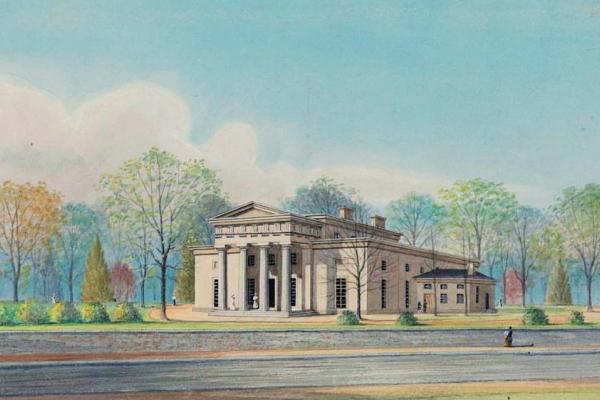

An extraordinary remnant of old Greenville is the former Pennsylvania Home for Working Blind Men. This late 19th century building complex is extant; though from 1979, it no longer trained and employed blind citizens. The first building to occupy this site on the Lancaster Pike (today 3514–3530 Lancaster Avenue) was the “Greenville Mansion,” an Italianate structure that would eventually lend its name to the surrounding neighborhood.

After the Civil War, the Protestant Episcopal Church purchased the mansion as its Mission House, a training school for foreign missionaries. In 1874, the Church sold the building to the Pennsylvania Home for Working Blind Men, whose operatives soon added brick buildings, including the “Workshop” and the “Factory,” in the hexagon formed by the Lancaster and 34th, 35th, and Warren streets.

In the 20th century, the Home for Working Blind Men, later renamed the Center for the Blind, would be financially strapped, meagerly endowed, and mismanaged, the Home’s leaders having failed to keep pace with “changes occurring in the education and training of blind adults in the United States.” By the 1960s, the Home’s facilities and programs were woefully outdated.10

“The multilated brick corpse stands against the squalid surroundings a decadent ruin amidst scattered glass and grafitti,” wrote the historian George Kettell in 1990.11 This gloomy assessment would require rethinking after the turn of the Millennium. In the 2010s, following a boom in upscale apartment development on and near Drexel University, developers renovated the brick building complex and marketed the units as “luxury apartments.”

1. Leon S. Rosenthal,A History of Philadelphia’s University City(Philadelphia: West Philadelphia Corp., 1963), pt. 8.

2. “Episcopal Parishes Consolidated,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 May 1890, via Philadelphia Studies.

3. Rosenthal, History of Philadelphia’s University City, pt. 8.

5. W. Wallace Weaver, "West Philadelphia: A Study of Natural Social Areas (PhD diss., University Pennsylvania, 1930), 63–64.

7. “Rents Are Low There,” The Times (Philadelphia), 18 February 1894.

8. Weaver, “West Philadelphia,” 50.

10. George H. Kettell, “End of a World: A History of the Pennsylvania Working Home for Blind Men from Its Beginning in 1874 until the Bankruptcy Proceedings in 1979” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1990), vi–viii.