A Streetcar Suburb in the City, 1854–1900: Part IV

Transportation innovation and real estate development cumulated in the creation of a streetcar suburb in the city by the end of the 19th century. Part IV highlight owner-occupied mansions, among other developments.

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. Focusing on blocks developed on the periphery of the University of Pennsylvania, Part IV highlights housing initiatives and owner-occupied mansions, some of which, in renovated form, now house university or healthcare-related activities.

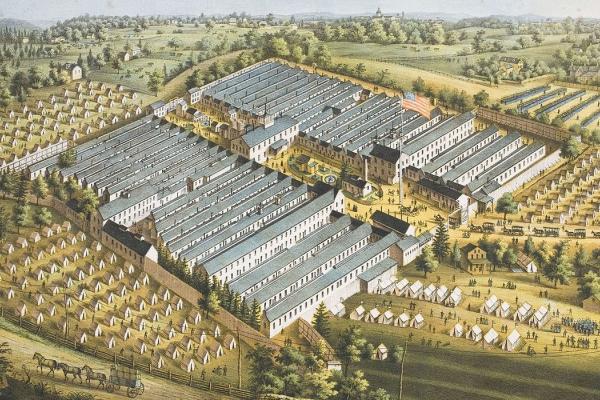

This article looks at the post-Civil War middle-class housing boom in the western part of the area that today is University City. We also take up owner-occupied mansions built by wealthy Philadelphians or their heirs.

Development on Pine Street and the Vicinity of South 40th Street and Baltimore Avenue

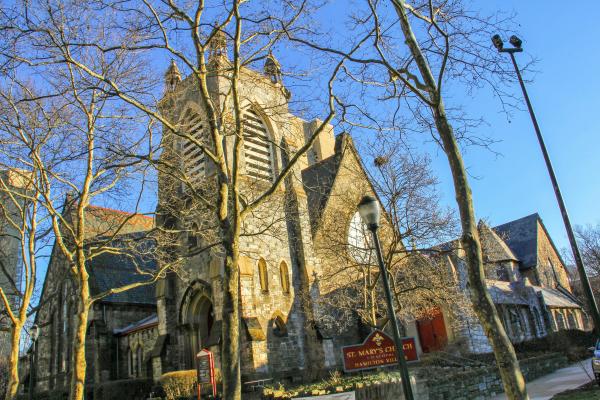

In the 1860s several developers operating on a smaller scale than Woodland or Hamilton Terrace built houses on Pine Street between 39th and 41st streets. Clergymen and lawyers, wholesalers, and financial agents and brokers bought these attached houses, which were disguised to appear as single mansions through such devices as “towers porches, roof pitches, and large bays.”1

Designed by Samuel Sloan and others, the Hamilton Family Estate development—a set of predominately Italianate detached and semi-detached, three-story residences occupied the south side of the 4000 block of Pine Street. Sloan and others also designed two Hamilton Family brownstone residences in the Italianate motif at 4039–41 Baltimore Avenue. Notable among other surviving structures from this period is the ornate Italianate brownstone at 4004–06 Pine Street, its proud connected houses separated by a large tower in the middle of the edifice.2

Annesley R. Govett developed the 3900 block of Pine Street around 1872. The Italianate/Greek Revival, redbrick row houses—residences today, in renovated form—were built by Jacob Wireman.3

Owner-Built Mansions in the University Neighborhood

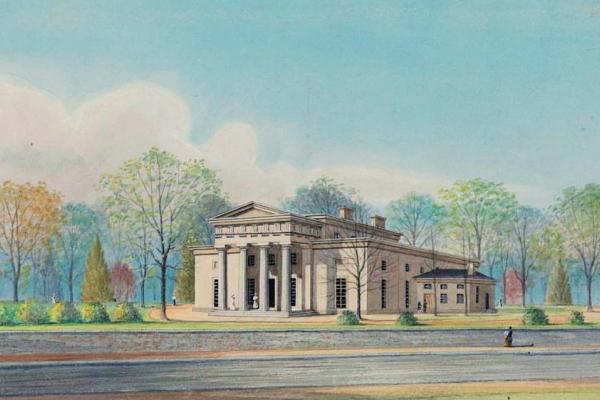

In 1852 the boosterish commissioners of the recently formed (pre-Consolidation Act) West Philadelphia District, which comprised Hamiltonville, Powelton, and Mantua, proclaimed the virtues of the emerging suburb:

As a place of residence, it may be safely said that no other location in the vicinity of Philadelphia offers superior attractions. The ground in general is elevated and remarkably healthy; the streets are wide, and many of them, bordered with handsome shade trees; a large portion of the District has been covered with costly and highly ornamental dwellings. New streets are being opened, graded, and paved; footwalks have been laid and gas introduced, and arrangements will soon be made for an ample supply of water. Omnibus lines have been established, which run constantly, day and evening, thus enabling residents to transact business in the City of Philadelphia and adjoining districts without inconvenience. A number of wealthy and influential citizens now reside in the District, and there is every indication that the tide of population will flow into it with unexampled rapidity.4

Acting individually, not as developers or housing speculators, a cadre of doctors, lawyers, judges, and businessmen built private mansions on the District’s main streets. The lawyer John C. Mitchell built a three-story mansion at 3905 Spruce Street, from which he commuted to his downtown office on Walnut Street. The mansion, originally built in the Italianate style, was purchased by the iron merchant Joseph D. Potts and rebuilt by the architectural firm Wilson Brothers in 1876, with “strong detail and bands of colored brick and tile.” Potts either inherited from a previous owner or himself built a carriage house in the rear of the mansion that served as a “stable and storage facility.”5

Potts lived at 3905 Spruce with his wife, Mary, until his death in 1893. In 1918, the house became home to Philadelphia’s International House. The University of Pennsylvania trustees acquired the property from International House in 1960. Today the building houses Penn Press. And since 2002, the carriage house has been home to Penn’s LGBTQ Center.6

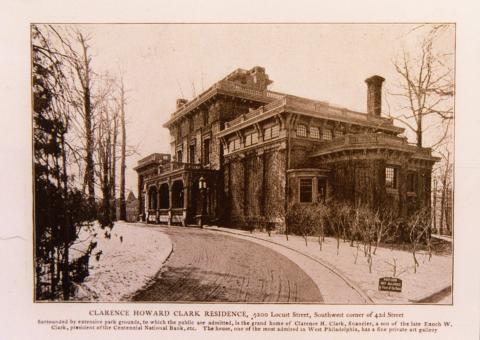

In the 1860s the Philadelphia banker Clarence H. Clark bought up swaths of woods and fields west of 40th Street for speculative purposes, and he built a brownstone Italianate mansion named “Chestnutwold” in 1871. The house and grounds comprised eight acres—the entire block of Locust–Spruce–42nd–43rd streets. In the mid-1890s Clark gave his name to Clark Park, a trapezoidal swath of land south and west of the intersection of 43rd Street and Baltimore Avenue. Clark deeded the land to the City in exchange for tax abatements on his properties in the immediate vicinity of the park.7

In 1884 Anthony Drexel Jr., the son and heir of the Philadelphia financial mogul and senior partner of J.P. Morgen, the nation’s leading financier, built a mansion at 3809 Locust Street. The building was designed by Thomas R. Williamson in the Queen Anne style. The mansion was one of three Drexel Family houses that formed a compound in the blocks from Walnut to Locust between 38th and 39th streets.

A third Drexel-compound house was built in 1891 for Anthony Drexel Jr.’s brother George Childs Drexel at 225 South 39th Street by Wilson Brothers. The two Drexel heirs’ houses are “Victorian survivors,” home today to two Penn fraternities, Sigma Chi and Alpha Tau Omega, respectively.

A third mansion, belonging to Anthony Drexel Sr. at 3814 Walnut Street, built in the mid-nineteenth century, was demolished at the turn of the last century, freeing the site for the soap manufacturer Samuel S. Fels to build a splendid redbrick, Colonial Revival mansion, which today is home to Penn’s Samuel Fels Center of Government.8

Adjacent to the Fels mansion, at 3806–8 Walnut, the cigar manufacturer Otto Eisenlohr built a “French-inspired country house” designed by the firm of Horace Trumbauer in 1910–11 and built of white limestone and green slate. The architectural historian George E. Thomas says that the principal architect for the house was probably Julian Abele, the first African American graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s architecture program, who had also studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris.9

Other owner-built houses in the West Philadelphia suburb were noteworthy:

- In 1893, William J. Swain, founder of the Philadelphia Record, built a mansion designed by William Decker at 3925 Chestnut Street. (Today the mansion is home to West Philadelphia’s Ronald McDonald House.)10

- Clarence Clark Jr., son of Clarence Howard Clark (see above) erected Clark House in 1889 on the southwest corner of 42nd and Spruce streets, across the street from his father’s estate. The architectural style is “simplified Romanesque revival.” This house today is an apartment house.11

1. Roger Miller and Joseph Siry, “The Emerging Suburb: West Philadelphia, 1850–1880, Pennsylvania History 47 no. 2 (April 1980), 124.

2. University City Historical Society, “West Philadelphia Streetcar Suburb Historic District,” n.d.; Miller and Siry, “Emerging Suburb,” 124.

3. Joseph Minardi, Historic Architecture in West Philadelphia, 1789–1930s (Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2011).

4. Miller and Siry, “Emerging Suburb,” 109–110.

5. George E. Thomas, University of Pennsylvania: The Campus Guide (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002), 157; Mark Frazier Lloyd, “‘Carriage House’ at the Rear of 3905 Spruce Street,” Penn History, University Archives and Records Center, August 2000, accessed from https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/3905-spruce, 5 March 2020.

6. John L. Puckett and Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 244; University of Pennsylvania Archives, Mapping Penn: Land Acquisitions 1870–Present; Lloyd, “‘Carriage House.’”

7. Bradley Peniston, “What’s in a Name: Clark Park,” 16 January 2014, accessed 7 April 2016 at http://hiddencityphila.org/2014/01/whats-in-a-name-clark-park/. See also “Historic Clark Mansion Makes Way for Progress,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, 7 April 1916, Chronicling America: America’s Historic Newspapers, accessed 7 April 2016 at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/.