A Streetcar Suburb in the City, 1854–1900: Part II

Transportation innovation and real estate development cumulated in the creation of a streetcar suburb in the city by the end of the 19th century. Part II focuses on the Haddington neighborhood and three other areas of residential development: 52d Street below Market, Baltimore Avenue between 43rd and 47th streets, and Satterlee Heights, east of Baltimore above 43rd.

By the end of the 19th century, West Philadelphia’s landscape was formed as a streetcar suburb in the city. But developments did not unfold instantly or uniformly. The building of homes did not proceed as a sequential push westward to the area’s western boundaries, but rather in pocketed ways. And even within pockets of development, the filling-in of home building occurred gradually. Part II emphasizes the Haddington neighborhood and three other areas of residential development: 52d Street below Market, Baltimore Avenue between 43rd and 47th streets, and Satterlee Heights, east of Baltimore above 43rd.

Here we look at Haddington and three other areas of late-19th-century residential development, relying on maps to trace these developments. Satterlee Heights, one of these areas, would fizzle as a real estate brand by the turn of the century.

Haddington

Haddington provides a counterpoint to other developments in West Philadelphia. It originated as a Colonial-era village market center on the western edge of Blockley Township, grew internally, and then became absorbed in the residential growth of West Philadelphia while maintaining a somewhat separate identity.

Ellet’s 1843 map presented Haddington as a well-defined community. The road from West Philadelphia to Haverford, that is, present-day Haverford Avenue, was Haddington’s east–west thoroughfare. The north-south Merion Meetinghouse and Darby Road crossed Haverford Avenue between present-day 65th and 66th streets. Ellet depicted about seventeen buildings on his map, which included a schoolhouse, a hotel, and a Methodist church.

Twenty years later, Smedley’s 1862 atlas showed Haddington composed of about three dozen buildings. A hotel stood on the southwest corner of Haverford Avenue and the Merion and Darby Road; a country store on the south side of Haverford between present-day 66th and 67th Streets; and the Haddington Methodist Church on the northeast corner of Haverford and present-day 67th. None of West Philadelphia’s first horse-drawn trolley lines came this far west. In the period before the Civil War, Haddington was little affected by the urban development taking place 30 blocks to the east.

By 1872, however, the West Philadelphia Passenger Railway had reached "downtown" Haddington. Hopkins’ 1872 atlas showed the trolley line originating at 41st Street and Haverford Avenue and proceeding west on Haverford Avenue to 54th Street. At 54th, the line turned one block south to Vine Street and then proceeded west again to 65th Street. There it turned north on 65th and returned to Haverford Avenue. At Haverford, it turned one block west to its terminus at 66th Street. Development immediately followed the construction of the trolley line. Housing, churches, and schools were all part of the change. There was also new employment in commerce and manufacture.

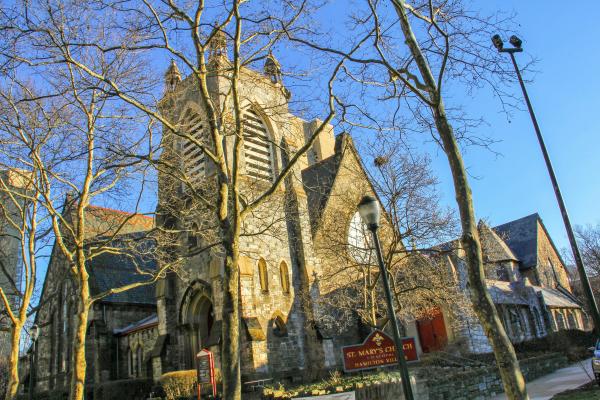

Bromley’s 1892 atlas showed the full extent of the new building. The "Major Whitesides Hotel" was gone, but the Haddington Methodist Church and the local public school both had new buildings at 63rd Street and Girard Avenue, one block south and three blocks east of their former locations. Also, south of Haverford Avenue, Episcopalians had built St. Barnabas Church at 65th Street and Girard; Presbyterians had built the Patterson Memorial Presbyterian Church at 63rd Street and Vine; and Roman Catholics had built Our Lady of the Rosary Church at 63rd and Callowhill. At 65th Street and Haverford stood the Bellevue Literary Institute and at 65th and Vine, the Home for Aged Couples of the Presbyterian Church.

North of Haverford Avenue, on a large tract of land fronting on 64th Street and Lansdowne Avenue, was the "Philadelphia Orphan Asylum." A little east of Haddington, at 61st and Haverford, was the Philadelphia Fire Department and Police Station. A major place of employment was John Sunderland’s "Coquanock Mills," which straddled a tributary of Cobbs Creek known as Indian Creek and was located at 69th Street and Haverford. With the extension of Philadelphia’s grid system of streets, the Colonial roads were superseded and vacated.

By 1892, the Darby and Merion Road had been closed north of Haverford Avenue and would also soon be closed south of Girard Avenue. By the turn of the 20th century, all that remained of the old road was one block of Atwood Street. Despite the gradual imposition of Philadelphia’s grid system of streets, Haddington, unlike Hestonville, retained its historic identity.

J.L. Smith’s 1911 atlas showed the historic crossroads of Haddington still independent of West Philadelphia’s urbanization, but the city was certainly near at hand. There was development as far west as 65th Street, but not beyond. The areas to the north, west, and south of Haddington were still mostly open land. The Philadelphia Orphan Asylum had sold its large tract of land for development in 1904, and east of 63rd Street the streets were lined with hundreds of new row houses.

The Market Street Elevated Railway was just six blocks south of Haverford Avenue and there was a major station at 63rd and Market streets. West Philadelphia commuters could easily walk to the El from the vicinity of Haddington and hundreds did, daily. Nevertheless, historic Haddington—that section of Haverford Avenue between 65th and 67th streets—had survived into the second decade of the twentieth century and would continue to occupy a neighborhood niche into the twenty-first.

52nd Street Below Market

Market Street, also known as the West Chester Pike, initially did not spur residential development as significantly as Lancaster. This may have been due to Haverford Avenue, which functioned as an east-west thoroughfare through much of the 19th century.

Ellet’s 1843 map showed the "West Chester Road" extending west from the Schuylkill all the way to the Philadelphia county boundary, but west of 40th Street the Road’s course traveled through open country. There were country inns and hotels along the Road, but very few other buildings.

Smedley’s 1862 atlas displayed the city grid pattern extending to Philadelphia’s limits, but the opening of those streets took several decades to accomplish. In the interim, earlier roads, usually at odds with the grid pattern, continued to be utilized.

Hopkins’ 1872 atlas showed no buildings at 52nd and Market Street. Even twenty years later there was no significant development at the intersection.

Bromley’s 1892 atlas indicated that 52nd Street had been opened at the intersection of Market Street, but the streets that paralleled it—51st and 53rd—were still only laid out and not opened. There was a "brick yard" on the northeast corner of 52nd and Market and a collection of 29 houses and stores on the northwest corner. On the southwest corner were a "nursery" and two houses, and on the southeast corner was open land. This was not yet an urban neighborhood.

The construction, however, of the Market Street Elevated Railway—and its station stop at 52nd Street—changed everything. E.V. Smith’s 1909 atlas and J.L. Smith’s 1911 atlas presented an altogether different picture from just 20 years earlier.

The brickyard on the northeast corner of 52nd and Market Street was gone and in its place were 56 row houses and storefronts. The 29 buildings on the northwest corner had swollen in number to 83. The nursery on the southwest corner had survived, at least for a few more years, but the corner itself now housed the "Market Street Title & Trust Company."

The southeast corner, open land in 1892, was now crowded with over 100 row houses and stores. No open land remained. 52nd and Market Streets became a bustling center of commerce and transportation, but it did so only in the first decades of the twentieth century (development occurring 50 and 60 years after the emergence of Hamilton Village just a mile or so to the east and Lancaster Avenue a mile to the north). There would few intersections like it anywhere in Philadelphia. With the introduction of the Market Street Elevated Railway—which opened in 1907—West Philadelphia became something of a city within a city.

For a full description of the Market Street Elevated and its impact on West Philadelphia, see at this website https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/market-street-elevated-el.

Baltimore Avenue Between 43rd and 47th Streets

"Darby Road" (present-day Woodland Avenue) was the third of the three mid-19th century spokes that radiated westward from the Market Street Permanent Bridge. For about a mile, it carried the traffic of all the roads leading to southwest Philadelphia and beyond. Then, at the intersection of present day 39th Street, Baltimore Avenue became the first to break off, heading in a more westward direction than the Darby Road, which turned almost due south.

Ellet’s 1843 map called Baltimore Avenue the "Chaddsford Turnpike" and showed that the Turnpike was a lonely stretch of road from Mill Creek (present-day 43rd Street) to the western limits of Philadelphia County. The Pennsylvania Railroad had yet to build its "West Chester Branch" through West Philadelphia and the farmers and mechanics who populated this area lived in scattered site housing. Twelve years later the railroad was in operation.

Barnes’ 1855 map showed Baltimore Avenue cutting through the streets of the city’s grid pattern, even though most of those streets had yet to be laid out and opened. Barnes also featured the "Cherry Tree Inn" at the intersection of Baltimore Avenue and Warrington’s Lane (present-day 47th Street), but otherwise there was virtually no development in this part of West Philadelphia.

Smedley’s 1862 atlas showed very little change from 1855. The land along both sides of Baltimore Avenue was still open.

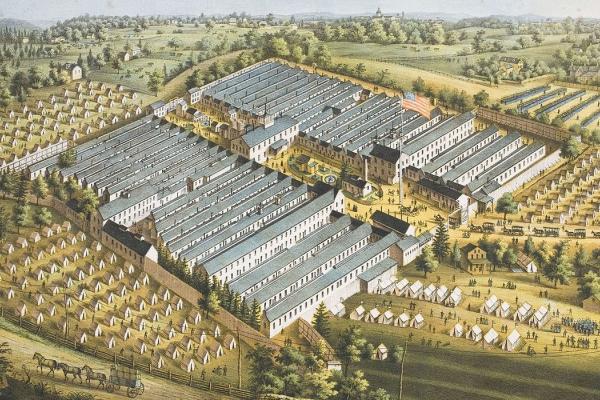

Development did come, however, first during the Civil War itself and then, rapidly, in the decade that followed. The chief factor in this change was the decision of the United States Army to locate a large, temporary military hospital on the north side of Baltimore Avenue, between 43rd and 45th streets. The grounds of the 4,500 bed hospital stretched northwestwardly from Baltimore Avenue as far as 46th and Pine Streets. Named Satterlee Hospital, after Richard S. Satterlee, Medical Purveyor of the United States Army, this 16-acre institution remained in operation only until 1865, when it was decommissioned and the land cleared of its temporary buildings.

Hopkins’ 1872 Atlas showed more than 60 single and twin houses projected for construction on Satterlee Heights, the name given to the area north of Baltimore between 43rd and 45th streets by speculators, notably the firm of Joseph Patton & Brothers. (See more below.)

Upscale housing lined 41st and 42nd Streets, both north and south of Baltimore Avenue. A little farther to the west, buildings lots had been laid out on 45th, 46th, and 47th streets south of Baltimore Avenue, but only a handful of houses had been completed. The Cherry Tree Hotel still stood at Baltimore Avenue and 47th Street, and beyond it the land was still open. Nevertheless, by the early 1870s, it was clear that Baltimore Avenue would be part of the greater residential development of West Philadelphia.

Fourteen years later, however, Baist’s 1886 Atlas showed that "streetcar suburbanization in a city" along Baltimore Avenue had stalled at 47th Street and that development involved institutions rather than housing. This section of West Philadelphia had become home to several charitable and benevolent institutions, which occupied relatively large tracts of land. This included: the "Home for Destitute Colored Children," at 46th Street and Woodland Avenue; the "Philadelphia Home for Incurables," at 48th Street and Woodland Avenue; "The Educational Home" (for American Indians), at 49th Street and Kingsessing Avenue (at the 49th Street station of the Pennsylvania Railroad); and the "Church Home for Children," at 58th Street and Baltimore Avenue (at the Angora station of the Pennsylvania Railroad).

At the city limits, the "Angora Cotton Mills" stood, accompanied by a cluster of 50 small houses and a Baptist church. The only new housing planned for this area was several blocks of row houses on 50th, 51st, and 52nd streets, just south of Baltimore Avenue. Bromley’s 1892 atlas showed the infilling of row houses along the south side of Baltimore Avenue west of 47th Street (though the north side remained open land). The pattern of urbanization was confirmed by Smith’s 1909 atlas, which demonstrated the dominance of the row house all along the north side of Baltimore Avenue. By the first decades of the twentieth century, Baltimore Avenue then had a mix of prominent charitable institutions and residences.

Satterlee Heights and Speculative Development North of Baltimore Avenue

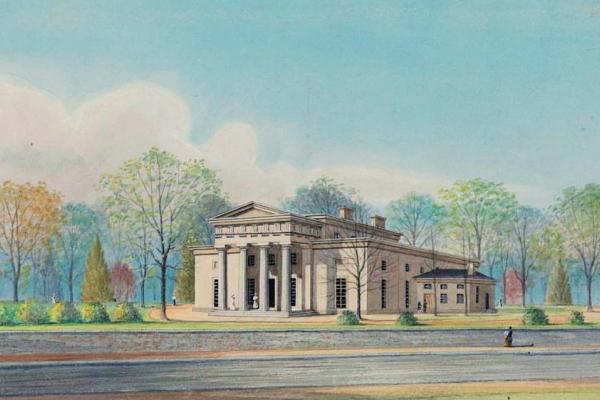

Between 1870 and 1880, the city extended its street grid to include undeveloped lands that were held as private estates west of 45th Street below Market Street. The estate owners, who resided in plush mansions west of old Hamiltonville, began to sell off parcels to real estate speculators willing to take the risk that West Philadelphia’s reputation as an attractive suburb would draw home buyers to the district’s “crab-grass frontier.” These developers divided their new acquisitions into lots for houses, anticipating a housing boom that would be slow in coming.

A case in point of stymied development was the previously mentioned Satterlee Heights, as the project area roughly from Spruce to Lombard (now Larchwood) streets between 43rd and 45th streets was known (a name that honored the Civil War Satterlee Military Hospital, which had operated nearby in the 1860s). Economic uncertainty after the Panic of 1873 stymied developers’ plans for these holdings in the short term. Meanwhile, the blocks closer to 40th Streets, where wealthier houses were located and lot purchases remained a good investment, filled up with row houses.1

Arrival of Electric Trolleys

Until the late 19th century, Philadelphians relied on horsecar trolleys to move about the city. In 1885 the Philadelphia Traction Company, responding to public demand for a faster, more efficient (i.e., mechanized) mode of transportation, installed a cable car line on Market Street. Several other lines followed, though cable cars were not widely adopted in the City. In the early 1890s, several independent companies experimented unsuccessfully with storage battery cars. After 1892, following the lead of the Philadelphia Traction Company, the city’s independent transportation companies outfitted their lines with overhead electricity wires for trolleys. By 1897, electric trolleys had completely displaced horsecars and cable cars.2

The truly transformative mode of transportation in West Philadelphia, the trains of the Market Street Elevated, would arrive a decade later and spur the area’s rapid population and housing growth.

For a full description of turn-of-the-last-century transportation developments, see at this website: https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/electric-streetcars-and-philadelphia-rapid-transit-company.

To summarize “A Streetcar Suburb in the City,” Part I and Part II, maps and atlases from the 1840s to the first decade of the 20th century reveal an overall but uneven, pocketed development of West Philadelphia as a dense residential area being transformed as a suburb in the city. Development occurred laterally along transportation corridors and within quadrants.

Some neighborhoods like Mantua filled in quickly and densely with row houses; others, like nearby Powelton, maintained a stately quality with detached homes or twins on landscaped plots of land or became occupied in stages (Baltimore Avenue, for example). Some, like Hamilton Village, emerged directly from the extension of streetcar lines across the Schuylkill River; Haddington, on the other hand, grew internally and only later merged with westward-moving transportation and real estate developments, though without losing its identity. In all instances, however, West Philadelphia neighborhoods became not just places of homes, but of various institutions as well.

1. The last City atlas to show the name Satterlee Heights was J.D. Scott’s “Atlas of the 24th and 27th Wards, Philadelphia.”

2. "History, Organization and Financial Characteristics of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company,” Street Railway Journal 26, no. 13 (1905): 479–88; Charles W. Cheape, Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), 174. For the social, cultural, and political contexts of these developments, see Nathaniel Burt and Wallace E. Davies, “The Iron Age: 1876–1905,” in Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, ed. Russell F. Weigley (New York: Norton, 1982), 471–523; in the same volume: Lloyd B. Abernethy, “Progressivism: 1905–1919,” pp. 524–565; Edwin O. Lewis, “Philadelphia’s Relation to the Rapid Transit Company,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 31 (May 1908): 66–77.